A few years ago Viorica, a Romanian friend of mine who was translating Ramana literature into Romanian, asked me to do an interview by email that she could use as an introduction to one of my books that was going to be published in Romanian. We started out with questions on my early years in Tiruvannamalai, but somehow the project petered out without coming to any apparent conclusion. This is as far as we got…

Question: Can you describe your first visit to Sri Ramanasramam? The very first day, time of day, first feelings, emotions, happenings, first people you met, first impressions, expectations, disappointments, experiences, etc?

David: When I travelled to Tiruvannamalai for the first time, I had no idea what I would find at my destination. I had found my first Ramana books – those written and edited by Arthur Osborne – in my local university bookstore in 1974. I asked one of the staff there to order all the other books on Bhagavan that were listed in his notes, but the bookstore received no response from Ramanasramam, the publisher. I assumed from this that the ashram didn’t exist any more. The books I had read had first appeared in the early 1950s. I assumed that after Bhagavan passed away, the ashram had ceased to exist as an institution that people visited and stayed in.

Since I know that this was my thought process, I find it odd, looking back, that I was so determined to come to Tiruvannamalai. I came overland to India from the UK on buses and trains, a trip that took a little over two weeks. I didn’t stop at too many places on the way. I had done the overland route to India before, in 1972, and spent months enjoying all the places on the way. This time I knew I just wanted to be in India. In the 1970s the overland route was a lot cheaper than a plane ticket. I didn’t have much money, and I wanted the trip to last as long as possible.

Once I had arrived in Delhi, I discovered that there were no trains to Chennai for two weeks. They were all booked up for the summer holidays. This was May, 1976. It was the height of summer and I had no desire to be cooped up in Delhi for the two weeks I had to wait to catch the train.

I went to the Motilal Banarsidas bookstore in Old Delhi and there, to my delight, I found all the books that I had previously only seen as footnotes in Osborne’s books. I bought about ten ashram books, including Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, Day by Day with Bhagavan, Letters from Sri Ramanasramam, and so on. Armed with a back pack full of exciting reading material, I caught a bus to Manali, a hill station north of Delhi. I think the trip took about fourteen hours, but it was well worth it. I ended up 6,000 feet up a mountain on the outskirts of what was then still a small village. I rented a room about two miles from Manali and spent 10-12 glorious days sitting in the mountains and forests, wallowing in a feast of Ramana literature, none of which I had seen before. Occasionally, people would ask me why I had come to India. When I told them I was on a pilgrimage to Tiruvannamalai, no one had ever heard of either the place or of Bhagavan.

I remember one sadhu I showed a Bhagavan book to ‘cursing’ me for being arrogant, saying I was a typical foreigner who thought he knew everything. All I did was show him a book and say I was on my way to Ramana Maharshi’s ashram. He had no idea who Bhagavan might be, and didn’t care.

The Delhi-Chennai train took about fifty-five hours, a lot more than the scheduled timetable predicted. It stopped, or was stranded, for hours in many remote locations. I was on the top bunk, about eighteen inches from the steel roof, reading my books. It was mid-summer. Every time the train stopped, the radiant heat from the roof had me drenched in sweat within seconds. The ceiling fans just couldn’t keep up with it. By the time we arrived in Chennai I was in no condition to face another trip, so I stayed for a day and a night in a cheap hotel near the train station.

At some point during my recuperation day I found myself on the beach, reading one of my new Ramana books. Someone came up to me, noticed what I was reading, and started a conversation. He mentioned that he had been to Ramanasramam himself a few weeks before. At this point I had been travelling for well over a month. I had covered about 6,000 miles and I was only a five-hour bus ride from my destination. This, though, was the first confirmation I had had that there really was a place called Ramanasramam which devotees could visit. I knew there would be a grave that I could pay my respects to, but this was the first time I received information that there was a functioning ashram there as well.

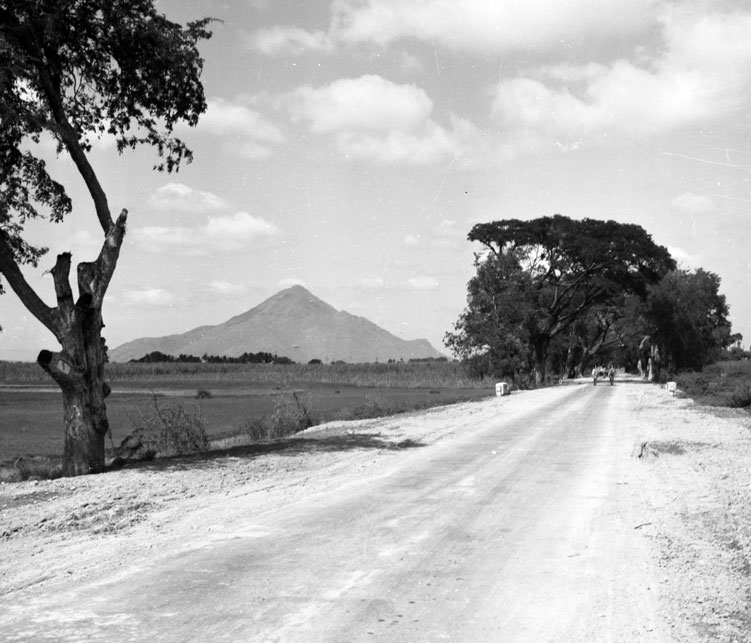

I took an early morning bus the following day. I had no idea how long the trip would be, and for hours there were no signs on the road that indicated how far away Tiruvannamalai might be. However, once the bus passed Tindivanam, the kilometre marker signs for Tiruvannamalai (and other towns on the route) kept popping up every few minutes. I still remember my rising sense of excitement as the numbers went down: 35 km, 28 km, 24 km, and so on. I know now that Arunachala is visible about 24 km away on that road, but on my first visit I couldn’t be sure whether I was really looking at the mountain or not. When the distance came down to single figures, I knew I really was looking at Arunachala for the first time.

I walked from the old bus stand (near to where the train station is today) into town and had a lunch. It was June 17th, 1976. I ate in a place called The Modern Café, which might have been modern fifty years before, but on the day I came, it was just sweaty and squalid. I didn’t care though. I knew I was only a few minutes from Ramanasramam. I think I would have walked to the ashram had I known where it was. I liked walking everywhere when I was young, even in the fierce heat with a heavy backpack. Instead, I hailed a cycle rickshaw which pedalled me slowly through town.

I kept scanning the sides of the road for some sign that I was nearing my destination. The first was a painted sign pointing down a side road that said ‘Ma Taleyarkhan’. I remembered her name from one of Osborne’s books, and as I did so a physical jolt went through my body. I knew I must be close.

Since the ashram was only about 200 metres from that sign, I soon found myself standing in the office, asking if I could stay.

‘For how long?’ someone asked.

‘A few weeks,’ I replied.

A spontaneous eruption of laughter went round the office. I think they were collectively amused at the effrontery of this foreigner who had just walked in and asked for such a long stay. I didn’t know then that the rule was three days for new people they didn’t know. Nowadays, no one is admitted unless he or she has written in advance. At that time the office was just one room, with three or four workers sitting cross-legged on the floor behind low, sloping desks. Everyone could hear everyone else’s business.

When the laughter died down, I was told ‘Three days,’ and a man was called to take me to my room. I was given the one where Balaram Reddy and Venkataraman (the ashram president) later spent many years. It was a lot more primitive when I stayed there. There was a bed and a fan, but no bathroom or toilet.

I had put my life on hold to come to India on this pilgrimage. I had travelled for weeks to get to this place, only to be told I could only stay three days. Somehow, it didn’t bother me in the least. Simply by existing, the ashram had exceeded my expectations. I had had a recurring fantasy while I was travelling across Asia of turning up in Tiruvannamalai and having to poke around in a jungle for a headstone that bore Bhagavan’s name. I was therefore happy that the institution was still in business, even if it wasn’t very welcoming to new people.

A few minutes after being shown to my room I found myself walking around the ashram, looking for Bhagavan’s samadhi. I wanted to pay my respects and announce my arrival as soon as possible. Unfortunately, it was the middle of the day. All the big buildings were locked up, and none of them had any signs on them. They didn’t appear until the 1980s. The few people I saw were all lying full-length on the ground, having their customary siesta. It was about 2 p.m. on a hot summer day. With no signs to help me, and no one to ask directions from, I wandered around rather aimlessly for about fifteen minutes, trying to work out what each of the buildings might be. I was somewhat handicapped by not having any idea of what a Hindu samadhi might look like. In the end – and I always laugh when I recollect this – I decided that Chinnaswami’s samadhi must be Bhagavan’s. I went up to it and did a full-length prostration there. If there had been more conscious people in the ashram at that hour, I am sure that my action would have been greeted with another round of laughter.

As I continued with my perplexing tour of the ashram’s buildings, I encountered another foreigner who seemed to be doing much the same thing. I met him in the space between the kitchen door and the storeroom entrance. He wanted to try to find Skandashram, and asked me if I felt like coming with him. I am amazed as I write this that I thought that walking a mile up the hill on a hot summer’s afternoon struck me as a fun and desirable way to pass the time. I jumped at the chance.

I can’t recollect how or from whom we managed to get directions, but soon we were on the hill. I don’t remember much about the journey either, but I do remember sitting inside Skandashram and meditating for about thirty minutes. I think I was a bit too excited to be truly quiet, but I still remember it as a moving and memorable occasion. I had checked in with Bhagavan by mistakenly prostrating at Chinnaswami’s samadhi, and I had checked in with Arunachala by walking on its slopes and by meditating at Skandashram. My day and my arrival somehow felt complete.

I don’t have many memories of those first three days. I do remember the almost-empty dining room, which was still divided into brahmin and non-brahmin sections, as it was in Bhagavan’s day. I think there were probably only twelve to fifteen people on the non-brahmin side. It wasn’t like today when hundreds are fed at every meal. I also remember discovering the old hall and taking to it like a duck to water. In my first few months at Arunachala I spent most of my waking hours there.

On my second day I met Raja Iyer, the old postmaster. I knew I had to find a place to stay outside the ashram, so I asked him to show me around. After looking at a few possibilities, it was Lucia Osborne who eventually took me in, giving me a room at the back of her house for Rs 30 a month. I spent the next eighteen months there.

Question: Your journey to Tiruvannamalai shows a strong determination to reach Ramanasramam. When you were asked how long you wanted to stay in the ashram, you answered ‘A few weeks’. What where your plans and expectations about those few weeks you intended to spend there? Did you have any? How did you see your future life in India at that time? What was it that you were really looking for? How did things really turn out to be? I ask because those ‘few weeks’ actually extended to a life time.

Answer: I don’t think I had any expectations because I had no idea what to expect. The period of ‘a few weeks’ was a bit arbitrary. I didn’t think I could afford to stay there much longer, and I definitely didn’t go there with any idea of settling down. I had a gap of a few months in my life, some money in my pocket, and a desire to connect with Bhagavan.

I had spent most of the previous year in Ireland, doing self-enquiry in a small rented house, and growing most of my own food. I had to give up living there because my landlady, who had gone to live in Australia with her husband, wanted to reclaim it. Her husband had had a major accident, and with no medical insurance, she needed to sell the house to pay his bills. I then went to Israel for a few months, primarily because I didn’t want to have a cold and wet winter in the UK or Ireland. My plan was to return to another house in Ireland once I had finished my spell in Israel and completed my pilgrimage to India.

What was I looking for? I don’t think I was looking for anything. I just felt an irresistible urge to come to Tiruvannamalai to connect with the place where Bhagavan lived most of his life. In retrospect it seems such an odd and bizarre thing for me to have done. I am sure I had reasons at the time that made perfect sense to me, but looking back on that period I can’t recollect any sensible ones.

With hindsight I would say that Arunachala pulled me here, and that whatever reasons I might have had at the time were just my mind’s attempt to construct a coherent narrative and justification for what was going on.

I remember Bhagavan telling a visitor once that it was the power of Arunachala that brings everyone here, including him. Our brains might think of a sensible reason or excuse to go to Arunachala once that power has manifested, but it is the pulling power of the mountain that is the real cause of our journey.

Some of us have a script, a prarabdha, to be here. The body and mind will feel the pull, start moving in this direction, after which we think up a rational reason to justify the trip.

There have been some interesting experiments in neuroscience in the last few years. It is possible to monitor the parts of the brain that make the body do things, while simultaneously checking other corners of the brain that take the decision to perform the actions. Much to the scientists’ consternation, it has been discovered that the body starts to perform an act a few seconds before the decision to do it manifests in the brain. This has rather alarming implications for our belief in free will. It seems that the body has a script, that it starts executing its actions before the ‘I’ inside us ‘decides’ to do them. If the experiments stand the test of time, they really will demonstrate that the ‘I am the doer’ idea is an artificial construct, one that is there merely to sustain the mistaken idea that we are in charge of our destiny, and that we can choose and decide the things we do in this life.

So, some power drew me here and kept me here, and my mind had to run along behind, justifying it.

It didn’t take me long to fall in love with this place. Quite early on I knew that I wanted to stay in this place as long as possible. Again, I don’t know why. However, in opposition to this there was a recurring feeling: ‘I don’t have much money. Sooner or later I will have to go home.’

Destiny had other plans, though. At some point in my first year here I was walking around Bhagavan’s samadhi when it suddenly dawned on me, ‘I don’t have to go home. This is my home. I don’t need to go anywhere at all.’

It was like a great weight being suddenly lifted off my shoulders. I didn’t need to go anywhere because I had found my way ‘home’.