[If you have come to this page looking for information on how to practise Ramana Maharshi’s teachings on ‘Who am I?’, I suggest you follow this link to a separate section of the site where detailed instructions are given. The link is here.

This site also contains an extensive section on self-enquiry that contains many videos and articles which explain the practice of ‘Who am I?’ The link is here.

What follows on this page is a translation of and commentary on Ramana Maharshi’s essay Who am I?]

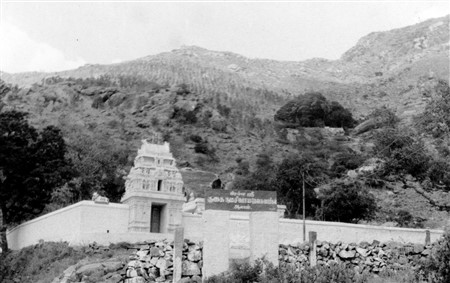

This essay, composed by Bhagavan in the mid-1920s, originated with answers that he wrote in the sand in 1901. For many years it was the standard introduction to Bhagavan’s teachings. Its publication was subsidised and copies in many languages were always available in the ashram’s bookstore, enabling new visitors to acquaint themselves with Bhagavan’s practical advice.

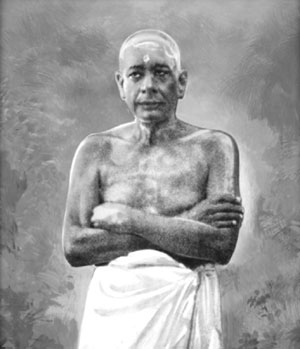

Although it continues to be a standard primer for those who want to know what Bhagavan taught, parts of Who Am I? are quite technical. Since Sivaprakasam Pillai, the devotee who asked the questions in 1901, was well acquainted with philosophical terminology, Bhagavan freely used technical terms in many of his answers. I have explained many of these in notes that alternate with the text. The words of the original essay are printed in bold type. Everything else is my own commentary or explanation.

Since these explanations were originally answers to Sivaprakasam Pillai’s questions, I have included some of the original questions in my own notes. Before each new section of Who am I? begins, I give, if possible, the question that prompted it. Towards the end of the essay Bhagavan took portions from different answers and amalgamated them into single paragraphs, making it hard to know for sure whether he is answering a particular question or merely giving a teaching statement.

The paragraph that begins the essay was not given out in response to a question. It was composed by Bhagavan when he was rewriting the work in the 1920s. Many philosophical works begin with a statement about the nature of happiness and the means by which it can be attained or discovered. Bhagavan has followed this tradition in this presentation.

Every living being longs to be perpetually happy, without any misery. Since in everyone the highest love is alone felt for oneself, and since happiness alone is the cause of love, in order to attain that happiness, which is one’s real nature and which is experienced daily in the mindless state of deep sleep, it is necessary to know oneself. To achieve that, enquiry in the form ‘Who am I?’ is the foremost means.

Question: Who am I?

‘Who am I?’ The physical body, composed of the seven dhatus, is not ‘I’. The five sense organs… and the five types of perception known through the senses… are not ‘I’. The five parts of the body which act… and their functions… are not ‘I’. The five vital airs such as prana, which perform the five vital functions such as respiration, are not ‘I’. Even the mind that thinks is not ‘I’. In the state of deep sleep vishaya vasanas remain. Devoid of sensory knowledge and activity, even this [state] is not ‘I’. After negating all of the above as ‘not I, not I’, the knowledge that alone remains is itself ‘I’. The nature of knowledge is sat-chit-ananda [being-consciousness-bliss].

Vasanas is a key word in Who am I? It can be defined as, ‘the impressions of anything remaining unconsciously in the mind; the present consciousness of past perceptions; knowledge derived from memory; latent tendencies formed by former actions, thoughts and speech.’ It is usually rendered in English as ‘latent tendencies’. Vishaya vasanas are those latent mental tendencies that impel one to indulge in knowledge or perceptions derived from the five senses. In a broader context it may also include indulging in any mental activity such as daydreaming or fantasising, where the content of the thoughts is derived from past habits or desires.

The seven dhatus are chyle, blood, flesh, fat, marrow, bone and semen. The five sense organs are the ears, skin, eyes, tongue and nose, and the five types of perception or knowledge, called vishayas, are sound, touch, sight, taste and smell. The five parts of the body that act are the mouth, the legs, the hands, the anus, and the genitals and their functions are speaking, walking, giving, excreting and enjoying. All the items on these lists are included in the original text. I have relegated them to this explanatory note to facilitate easy reading.

The five vital airs (prana vayus) are not listed in the original text. They are responsible for maintaining the health of the body. They convert inhaled air and ingested food into the energy required for the healthy and harmonious functioning of the body.

This paragraph of Who am I? has an interesting history. Sivaprakasam Pillai’s original question was ‘Who am I?’, the first three words of the paragraph. Bhagavan’s reply, which can be found at the end of the paragraph, was ‘Knowledge itself is “I”’. The nature of knowledge is sat-chit-ananda.’ Everything else in this paragraph was interpolated later by Sivaprakasam Pillai prior to the first publication of the question-and-answer version of the text in 1923. The word that is translated as ‘knowledge’ is the Tamil equivalent of ‘jnana’. So, the answer to that original question ‘Who am I?’ is, ‘Jnana is “I” and the nature of jnana is sat-chit-ananda’.

When Bhagavan saw the printed text he exclaimed, ‘I did not give this extra portion. How did it find a place here?’

He was told that Sivaprakasam Pillai had added the additional information, including all the long lists of physical organs and their functions, in order to help him understand the answer more clearly. When Bhagavan wrote the Who Am I? answers in an essay form, he retained these interpolations but had the printer mark the original answer in bold type so that devotees could distinguish between the two.

This interpolation does not give a correct rendering of Bhagavan’s teachings on self-enquiry. In the following exchange (taken from Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, talk no. 197) Bhagavan explains how self-enquiry should be done, and why the ‘not I, not I’ approach is an unproductive one:

Question: I begin to ask myself ‘Who am I?’, eliminate the body as not ‘I’, the breath as not ‘I’, and I am not able to proceed further.

Bhagavan: Well, that is as far as the intellect can go. Your process is only intellectual. Indeed, all the scriptures mention the process only to guide the seeker to know the truth. The truth cannot be directly pointed at. Hence, this intellectual process.

You see, the one who eliminates the ‘not I’ cannot eliminate the ‘I’. To say ‘I am not this’ or ‘I am that’ there must be an ‘I’. This ‘I’ is only the ego or the ‘I’-thought. After the rising up of this ‘I’-thought, all other thoughts arise. The ‘I’-thought is therefore the root thought. If the root is pulled out all others are at the same time uprooted. Therefore, seek the root ‘I’, question yourself ‘Who am I?’ Find the source and then all these other ideas will vanish and the pure Self will remain.

Question: Will there be realisation of the Self even while the world is there, and taken to be real?

If the mind, which is the cause of all knowledge and all actions, subsides, the perception of the world will cease. [If one perceives a rope, imagining it to be a snake] perception of the rope, which is the substratum, will not occur unless the perception of the snake, which has been superimposed on it, goes. Similarly, the perception of one’s real nature, the substratum, will not be obtained unless the perception of the world, which is a superimposition, ceases.

Question: What is the nature of the mind?

That which is called ‘mind’, which projects all thoughts, is an awesome power existing within the Self, one’s real nature. If we discard all thoughts and look [to see what remains when there are no thoughts, it will be found that] there is no such entity as mind remaining separate [from those thoughts]. Therefore, thought itself is the nature of the mind. There is no such thing as ‘the world’ independent of thoughts. There are no thoughts in deep sleep, and there is no world. In waking and dream there are thoughts, and there is also the world. Just as a spider emits the thread of a web from within itself and withdraws it again into itself, in the same way the mind projects the world from within itself and later reabsorbs it into itself. When the mind emanates from the Self, the world appears. Consequently, when the world appears, the Self is not seen, and when the Self appears or shines, the world will not appear.

If one goes on examining the nature of the mind, it will finally be discovered that [what was taken to be] the mind is really only one’s self. That which is called one’s self is really Atman, one’s real nature. The mind always depends for its existence on something tangible. It cannot subsist by itself. It is the mind that is called sukshma sarira [the subtle body] or jiva [the soul].

Question: What is the path of enquiry for understanding the nature of the mind?

That which arises in the physical body as ‘I’ is the mind. If one enquires, ‘In what place in the body does this “I” first arise?’ it will be known to be in the hridayam. That is the birthplace of the mind. Even if one incessantly thinks ‘I, I’, it will lead to that place. Of all thoughts that arise in the mind, the thought ‘I’ is the first one. It is only after the rise of this [thought] that other thoughts arise. It is only after the first personal pronoun arises that the second and third personal pronouns appear. Without the first person, the second and third persons cannot exist.

Hridayam is usually translated as ‘Heart’, but it has no connection with the physical heart. Bhagavan used it as a synonym for the Self, pointing out on several occasions that it could be split up into two parts, hrit and ayam, which together mean, ‘this is the centre’. Sometimes he would say that the ‘I’-thought arises from the hridayam and eventually subsides there again. He would also sometimes indicate that the spiritual heart was inside the body on the right aside of the chest, but he would often qualify this by saying that this was only true from the standpoint of those who identified themselves with a body. For a jnani, one who has realised the Self, the hridayam or Heart is not located anywhere, or even everywhere, because it is beyond all spatial concepts. The following answer from Day by Day with Bhagavan, 23rd May 1946, summarises Bhagavan’s views on this matter:

I ask you to see where the ‘I’ arises in your body, but it is not really quite true to say that the ‘I’ rises from and merges on the right side of the chest. The Heart is another name for the reality, and it is neither inside nor outside the body. There can be no in or out for it since it alone is… so long as one identifies with the body and thinks that he is in the body, he is advised to see where in the body the ‘I’-thought rises and merges again.

A hint of this can also be found in this paragraph of Who am I? in the sentence in which Bhagavan asks devotees to enquire ‘In what place in the body does this “I” first arise?’

Ordinarily, idam, which is translated here as ‘place’, means only that, but Bhagavan often gave it a broader meaning by using it to signify the state of the Self. Later in the essay, for example, he writes, ‘The place [idam] where even the slightest trace of “I” does not exist is swarupa [one’s real nature]’.

Sadhu Natanananda, on the flyleaf of his Tamil work Sri Ramana Darshanam, records a similar statement from Bhagavan: ‘Those who resort to this place [idam] will obtain Atma-jnana [Self-knowledge] automatically.’ Clearly, he cannot be speaking of the physical environment of his ashram because paying a visit there didn’t necessarily result in enlightenment.

So, when Bhagavan writes ‘In what place…’ he is not necessarily indicating that one should look for the ‘I’ in a particular location. He is instead saying that that the ‘I’ rises from the dimensionless Self, and that one should seek its source there.

As he once told Kapali Sastri, ‘You should try to have rather than locate the experience’. (Sad Darshana Bhashya, pp. xvii-xix)