A dialogue between David Godman and Maalok, an Indian academic now teaching in America.

Maalok: Ramana Maharshi has had a lasting influence on your life. For those of us who don’t know much about the Maharshi, could you please share some of the salient aspects of his life that have influenced you deeply.

David: About two or three times a year someone asks me this question, ‘Summarise Ramana Maharshi’s life and teachings in a few words for people who know little or nothing about him’. It’s always hard to know where to start with a question like this.

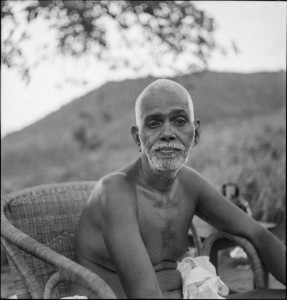

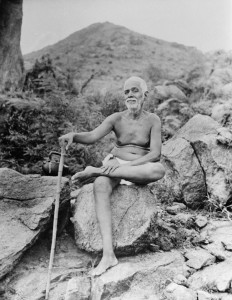

Let me say first that Ramana Maharshi was one of the most highly regarded and widely respected spiritual figures that twentieth-century India produced. I can’t think of any other candidate who is as persistently held out to be an example of all that is best in the Hindu spiritual tradition. Everyone reveres him as the perfect example of what a true saint and sage ought to be.

How did this come about? While he was still in his teens Sri Ramana underwent a remarkable, spontaneous experience in which his individuality died, leaving him in a state in which he found his true identity to be the Self, the immanent and transcendent substratum. It was a permanent awakening that was truly remarkable because he had not previously had any interest in spiritual matters. He left his family home a few weeks later, without telling anyone where he was going, and spent the remainder of his life at the foot of Arunachala, a holy mountain and pilgrimage centre that is about 120 miles south west of Chennai.

After a few years there – a period in which he was largely oblivious to the world and his body – he began to attract devotees because there was a spiritual radiance emanating from him that many people around him experienced as peace or happiness. This, I think, is the secret of his subsequent fame and popularity. He didn’t get a reputation for being a great sage because of what he did or said. It came about because people, who arrived at his ashram with all kinds of questions and doubts, suddenly found themselves becoming quiet, peaceful and happy in his presence. There was a continuous, benign flow of energy coming off him that somehow evaporated the mental anxieties and busy minds of the people who came to see him. He didn’t ask people to come. People just came of their own accord. A 19th century American author once wrote that if you invent a better mousetrap, even if you try to hide yourself in the woods, people will beat a path to your door. People beat a path to Sri Ramana’s door – for many years he lived in very inaccessible places – because he had something far better than an improved mousetrap to offer; he had a natural ability to induce peace in the people around him.

Let me expand on this because this is the key to understanding both his state and the effect he had on other people. When he had his final experience at the age of sixteen, his mind, his sense of being an individual person, vanished forever, leaving him in a state of unassailable peace. He realised and understood that this was not some new experience that was mediated by and through his ‘I’, his sense of being an individual person. It was, instead, his natural state, something that is there all the time, but which is only experienced when the mind and its perpetual busy-ness is absent. By abiding in this natural and effortless state of inner silence he somehow charged up the atmosphere around him with a healing, quietening energy. People who came to see him spontaneously became happy, peaceful and quiet. Why? Because Sri Ramana himself was effortlessly broadcasting his own experience of happiness, peace and quietude in such a way that those people who were around him got an inner taste, an inner flavor of this natural state that is inherent to all of us. I should say that this power was not restricted to his physical vicinity, although it did seem to be stronger there. People who merely thought about him wherever they happened to be discovered that they could experience something of this peace simply through having this mental contact with him.

So, having given that background, I can now answer the question: ‘Who was Ramana Maharshi and what were his teachings?’

Sri Ramana Maharshi was a living embodiment of peace and happiness and his ‘teachings’ were the emanations of that state which helped other people to find and experience their own inner happiness and peace.

If all this sounds a little abstract, let me tell you a story that was passed on to me by Arthur Osborne’s daughter. In the 1940s their house was a kind of dormitory for all the stray foreigners who couldn’t find anywhere else to stay near Sri Ramana’s ashram. A miserable, crabby women appeared one evening, having been sent by the ashram. They put her up, gave her breakfast and sent her off to see Sri Ramana the next morning. She came back at lunchtime looking absolutely radiant. She was glowing with happiness. The whole family was waiting to hear the story of what happened, but she never said anything about her visit to the ashram. Everyone in the house was expecting some dramatic story: ‘He looked at me and this happened,’ or ‘I asked a question and then I had this great experience’. As the lunch plates were being cleared away, her hosts could not contain their curiosity any longer.

‘What happened?’ asked one of them. ‘What did Bhagavan do to you? What did he say to you?’

The woman looked most surprised. ‘He didn’t do anything. He didn’t say anything to me. I just sat there for the whole morning and then came back for lunch.’

She had been just one new person sitting in a crowd of people, but the power coming off Sri Ramana had been enough to wash away a lifetime of depression, leaving her with a taste of what lay underneath it: her own inherent, natural happiness and peace.

Sri Ramana knew that transformations such as these were going on around him all the time, but he never accepted responsibility for them. He would never say, ‘I transformed this woman’. When he was asked about the effect he was having on people, he would sometimes say that by continuously abiding in his own natural state of peace, a sannidhi, a powerful presence, was somehow created that automatically took care of the mental problems of the people who visited him. By abiding in silence as silence, this energy field was created, a field that miraculously transformed the people around him.

Your original question was, ‘Why has Ramana Maharshi influenced me so much?’ The answer is, ‘I came into his sannidhi and through its catalytic activity I discovered my own peace, my own happiness.’

Maalok: If somebody wants to start practising the teachings of Ramana Maharshi, where and how should they start?

David: This is another classic question: ‘What should I do?’ However, the question itself is misconceived. It is based on the erroneous assumption that happiness and peace are states that can be experienced by striving, by effort. The busy mind covers up the peace and the silence that is your own natural state, so if you put the mind in gear and use it to pursue some spiritual goal, you are usually taking it away from the peace, not towards it. This is a hard concept for many people to grasp.

People found their own inner peace in Sri Ramana’s presence because they didn’t interfere with the energy that was eradicating their minds, their sense of being a particular person who has ideas, beliefs, and so on. The true practice of Sri Ramana’s teachings is remaining quiet, remaining in a state of inner mental quiescence that allows the power of Sri Ramana to seep into your heart and transform you. This can be summarised in one of Sri Ramana’s classic comments: ‘Just keep quiet. Bhagavan will do the rest.’

If you use the phrase ‘practising the teachings,’ the following sequence is assumed: that Sri Ramana speaks of some goal that has to be attained, that he gives you some route, some practice, to reach that goal, and that you then use your mind to vigorously move towards that goal. The mind wants to be in charge of this operation. It wants to listen to the Guru, understand what is required, and then use itself to move in the prescribed direction. All this is wrong. Mind is not the vehicle one uses to carry out the teachings; it is, instead, the obstacle that prevents one from directly experiencing them. The only useful, productive thing the mind can do is disappear.

Sri Ramana himself always said that his true teachings were given out in silence. Those who were receptive to them were the ones who could get out of the way mentally, allowing Sri Ramana’s silent emanations to work on them. In the benedictory verse to his philosophical poem Ulladu Narpadu Sri Ramana wrote, and I paraphrase a little: ‘Who can meditate on that which alone exists. One cannot meditate on it because one is not apart from it. One can only be it.’ This is the essence of Sri Ramana’s teachings. ‘Be what you are and remain as you are without having any thoughts. Don’t try to meditate on the Self, on God. Just abide silently at the source of the mind and you will experience that you are God, that you are the Self.’

Maalok: Did the Maharshi give some guidelines on the kind of life one should lead? Activities that would help spiritual quests? I mean mundane things such as eating, sleeping, drinking, talking, family, marriage, sexuality, etc.

David: I think the key word here is ‘moderation’. On several occasions he said that moderation in eating, sleeping and speaking were the best aids to sadhana. He didn’t approve of or encourage excess of any kind. He didn’t, for example, encourage people to take vows of silence. He used to say, ‘If you can’t keep your mind still, what is the point of keeping your tongue still?’

Though he encouraged devotees to live decent, upright lives, he never imposed rigorous moral codes on them. He was happy if devotees took to brahmacharya naturally, but he didn’t see much point in suppressing sexual desires. Someone once told him that in Sri Aurobindo Ashram, the men and the women slept separately, even if they were married. His response was, ‘What is the point of sleeping separately if the desires are still there?’ If people who had desires and wanted to get rid of them came to him for advice, he would usually say that meditation would make them lose their strength. According to Sri Ramana, you don’t get rid of desires by suppressing them, or by not indulging in them, you get rid of them by putting your attention on the Self.

He didn’t look down on people who were married as people who had succumbed to their desires. He once told Rangan, one of his married devotees, that it was easier to realise the Self as a householder than as a sannyasin.

Sri Ramana didn’t think that renouncing habits or possessions was very beneficial. Instead, he asked people to go to the root of the problem and renounce the idea that they were individual people occupying bodies. He would sometimes say that even if you give up your job, your family and all your responsibilities and go to a cave and meditate, you still have to take your mind with you. While that mind is still there, exercising its tyranny, you haven’t really renounced anything that will do you any good in the long term.

Maalok: When the topic of Ramana Maharshi’s teachings comes up, most people think of self-enquiry, the practice of asking oneself ‘Who am I?’ You haven’t even mentioned this.

David: I’m laying the foundation, as they say in court. I’m trying to put it in a proper perspective. People came to Sri Ramana with the standard seekers’ question: ‘What do I have to do to get enlightened?’ One of his standard replies was the Tamil phrase ‘Summa iru‘. ‘Summa‘ means ‘quiet’ or ‘still’ and ‘iru‘ is the imperative of both the verb to be and the verb to stay. So, you can translate this as ‘Be quiet,’ ‘Be still,’ Stay quiet,’ ‘Remain still,’ and so on. This was his primary advice.

However, he knew that most people couldn’t naturally stay quiet. If such people asked for a method, a technique, he would often recommend a practice known as self-enquiry. This is probably what he is most famous for. To understand what it is, how it works, and how it is to be practiced, I need to digress a little into Sri Ramana’s views on the nature of the mind.

Sri Ramana taught that the individual self is an unreal, imaginary entity that persists because we never properly investigate its true nature. The sense of ‘I’, the feeling of being a particular person who inhabits a particular body, only persists because we continuously identify ourselves with thoughts, beliefs, emotions, objects, and so on. The ‘I’ never stands alone by itself; it always exists in association: ‘I am John,’ ‘I am angry,’ ‘I am a lawyer,’ ‘I am a woman,’ etc. These identifications are automatic and unconscious. We don’t make them through volition on a moment-to-moment basis. They are just the unchallenged assumptions that lie behind all our experiences and habits. Sri Ramana asks us to disentangle ourselves from all these associations by putting full attention on the subject ‘I’, and in doing so, prevent it from attaching itself to any ideas, beliefs, thoughts and emotions that come its way.

The classic way of doing this is to start with some experienced feeling or thought. I may be thinking about what I am going to eat for dinner, for example. So, I ask myself, ‘Who is anticipating dinner?’ and the answer, whether you express it or not, is ‘I am’. Then you ask yourself, ‘Who am I? Who or what is this ”I” that is waiting for its next meal?’ This is not an invitation to undertake an intellectual analysis of what is going on in the mind; it is instead a device for transferring attention from the object of thought – the forthcoming dinner – to the subject, the person who is having that particular thought. In that moment simply abide as the ‘I’ itself and try to experience subjectively what it is when it is shorn of all identifications and associations with things and thoughts. It will be a fleeting moment for most people because it is the nature of the mind to keep itself busy. You will soon find yourself in a new train of thought, a new series of associations. Each time this happens, ask yourself, ‘Who is daydreaming?’ ‘Who is worried about her doctor’s bill?’ ‘Who is thinking about the weather?’ and so on. The answer in each case will be ‘I’. Hold onto that experience of the unassociated ‘I’ for as long as you can. Watch how it arises, and, more importantly, watch where it subsides to when there are no thoughts to engage with.

This is the next stage of the enquiry. If you can isolate the feeling of ‘I’ from all the things that it habitually attaches itself to, you will discover that it starts to disappear. As it subsides and becomes more and more attenuated, one begins to experience the emanations of peace and joy that are, in reality, your own natural state. You don’t normally experience these because your busy mind keeps them covered up, but they are there all the time, and when you begin to switch the mind off, that’s what you experience.

It’s a kind of mental archaeology. The gold, the treasure, the inherent happiness of your own true state, is in there, waiting for you, but you don’t look for it. You are not even aware of it, because all you see, all you know, are the layers that have accumulated on top of it. Your digging tool is this continuous awareness of ‘I’. It takes you away from the thoughts, and back to your real Self, which is peace and happiness. Sri Ramana once compared this process to a dog that holds onto the scent of its master in order to track him down. Following the unattached ‘I’ will take you home, back to the place where no individual ‘I’ has ever existed.

This is self-enquiry, and this is the method by which it should be practised. Hold on to the sense of ‘I’, and whenever you get distracted by other things revert to it again. I should mention that this was not something that Sri Ramana said should be done as a meditation practice. It is something that should be going on inside you all the time, irrespective of what the body is doing.