I was sitting with a visitor in 2002, looking at a new book on Nisargadatta Maharaj that consisted of photos and brief quotes. I knew some of the people in the pictures and narrated a few stories about them. This prompted a wider and lengthy discussion on some of the events that went on in Maharaj’s presence. After she left I felt prompted to write down some of the things I had remembered since I had never bothered to record any of my memories of Maharaj before. As I went about recording the conversation, a few other memories surfaced, things I hadn’t thought about for years. This, therefore, is a record of a pleasant afternoon’s talk, supplemented by recollections of related incidents that somehow never came up.

Harriet: Every book I have seen about Maharaj, and I think I have looked at most of them, is a record of his teachings. Did no one ever bother to record the things that were going on around him? Ramakrishna had The Gospel of Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharshi had Day by Day, and a whole library of books by devotees that all talk about life with their Guru. Why hasn’t Maharaj spawned a similar genre?

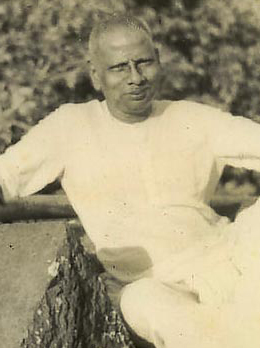

David: Maharaj very rarely spoke about his life, and he didn’t encourage questions about it. I think he saw himself as a kind of doctor who diagnosed and treated the perceived spiritual ailments of the people who came to him for advice. His medicine was his presence and his powerful words. Anecdotes from his past were not part of the prescription. Nor did he seem interested in telling stories about anything or anyone else.

Harriet: You said ‘rarely spoke’. That means that you must have heard at least a few stories. What did you hear him talk about?

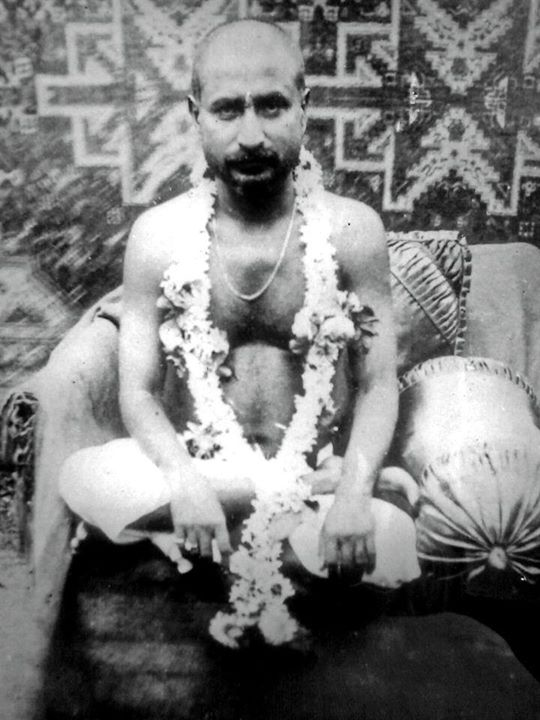

David: Mostly about his Guru, Siddharameshwar Maharaj, and the effect he had had on his life. I think his love for his Guru and his gratitude to him were always present with him. Nisargadatta Maharaj used to do five bhajans a day simply because his Guru had asked him to. Siddharameshwar Maharaj had passed away in 1936, but Nisargadatta Maharaj was still continuing with these practices more than forty years later.

I once heard him say, ‘My Guru asked me to do these five bhajans daily, and he never cancelled his instructions before he passed away. I don’t need to do them any more but I will carry on doing them until the day I die because this is the command of my Guru. I continue to obey his instructions, even though I know these bhajans are pointless, because of the respect and gratitude I feel towards him.’

Harriet: Did he ever talk about the time he was with Siddharameshwar, about what passed between them?

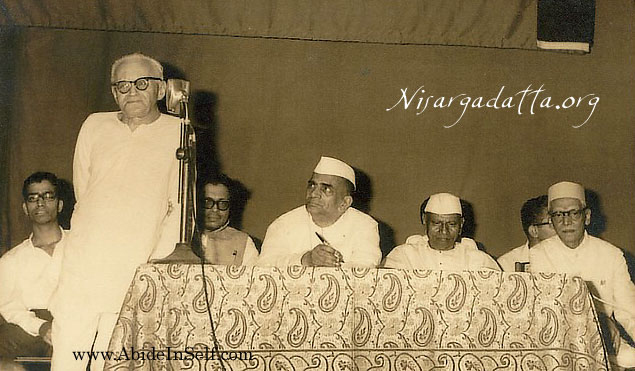

David: Not on any of the visits I made. Ranjit Maharaj once came to visit during one of his morning sessions. They chatted in Marathi for a few minutes and then Ranjit left.

Maharaj simply said, ‘That man is a jnani. He is a disciple of my Guru, but he is not teaching.’

End of story. That visit could have been a springboard to any number of stories about his Guru or about Ranjit, but he wasn’t interested in talking about them. He just got on with answering the questions of his visitors.

Harriet: What else did you glean about his background and the spiritual tradition he came from?

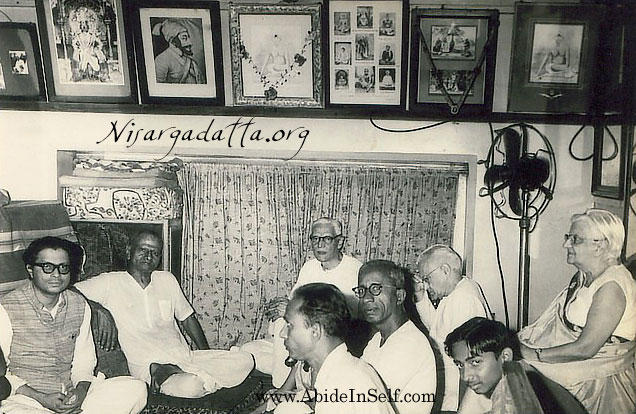

David: He was part of a spiritual lineage that is known as the Navnath Sampradaya. This wasn’t a secret because he had photos or pictures of many of the teachers from his lineage on his walls. He did a Guru puja every morning at the end of which he put kum kum on the foreheads of all the teachers in his lineage and on the photos of everyone else he thought was enlightened. I should mention that his walls were covered with portraits. Ramana Maharshi was there, and so were many other famous saints who were not part of his lineage. Mixed in with them were other pictures, such as one of Sivaji, a famous Marathi warrior from a few hundred years ago.

I once asked him why Sivaji had made it onto his walls, and he said, ‘My son wants me to keep it there. It’s the logo on our brand of beedis [hand-made cigarettes]. He thinks that if it is mixed in with all the other pictures that I do puja to, sales will increase.’

Harriet: What did he say about all these photos of the people from his lineage? Did he never explain who they were?

David: Never. I only found out what their names were a few years later when I came across a book by R. D. Ranade, who was in a Karnataka branch of the sampradaya. He, or rather his organization, brought out a souvenir that contained the same photos I had seen on Maharaj’s walls, along with a brief description of who they were.

I do remember one interesting story that Maharaj told about the sampradaya. He had been answering questions in his usual way when he paused to give us a piece of history:

‘I sit here every day answering your questions, but this is not the way that the teachers of my lineage used to do their work. A few hundred years ago there were no questions and answers at all. Ours is a householder lineage, which means everyone had to go out and earn his living. There were no meetings like this where disciples met in large numbers with the Guru and asked him questions. Travel was difficult. There were no buses, trains and planes. In the old days the Guru did the traveling on foot, while the disciples stayed at home and looked after their families. The Guru walked from village to village to meet the disciples. If he met someone he thought was ready to be included in the sampradaya, he would initiate him with the mantra of the lineage. That was the only teaching given out. The disciple would repeat the mantra and periodically the Guru would come to the village to see what progress was being made. When the Guru knew that he was about to pass away, he would appoint one of the householder-devotees to be the new Guru, and that new Guru would then take on the teaching duties: walking from village to village, initiating new devotees and supervising the progress of the old ones.’

I don’t know why this story suddenly came out. Maybe he was just tired of answering the same questions again and again.

Harriet: I have heard that Maharaj occasionally gave out a mantra to people who asked. Was this the same mantra?

David: Yes, but he wasn’t a very good salesman for it. I once heard him say, ‘My Guru has authorised me to give out this mantra to anyone who asks for it, but I don’t want you to feel that it is necessary or important. It is more important to find out the source of your beingness.’

Nevertheless, some people would ask. He would take them downstairs and whisper it in his or her ear. It was Sanskrit but you only got one chance to remember it. He would not write it down for you. If you didn’t remember it from that one whisper, you never got another chance.

Harriet: What other teaching instructions did Siddharameshwar give him? Was he the one who encouraged him to teach by answering questions, rather than in the more traditional way?

David: I have no idea if he was asked to teach in a particular way. Siddharameshwar told him that he could teach and give out the Guru mantra to anyone who asked for it, but he wasn’t allowed to appoint a successor. You have to remember that Nisargadatta wasn’t realised himself when Siddharameshwar passed away.

Harriet: What about personal details? Did Maharaj ever talk about his childhood or his family? Ramana Maharshi often told stories about his early life, but I don’t recollect reading a single biographical incident in any of Maharaj’s books.

David: That’s true. He just didn’t seem interested in talking about his past. The only story I remember him telling was more of a joke than a story. Some man came in who seemed to have known him for many years. He talked to Maharaj in Marathi in a very free and familiar way. No translations were offered but after about ten minutes all the Marathi-knowing people there simultaneously broke out into laughter. After first taking Maharaj’s permission, one of the translators explained what it was all about.

‘Maharaj says that when he was married, his wife used to give him a very hard time. She was always bossing him around and telling him what to do. ‘Maharaj do this, Maharaj go to the market and buy that.’

She didn’t call him Maharaj, of course, but I can’t remember what she did call him.

The translator continued: ‘His wife died a long time ago, when Maharaj was in his forties. It is usual for men of this age who are widowed to marry again, so all Maharaj’s relatives wanted him to find another wife. He refused, saying, “The day she died I married freedom”.’

I find it hard to imagine anyone bossing Maharaj around, or even trying to. He was a feisty character who stood no nonsense from anyone.

Harriet: From what I have heard ‘feisty’ may be a bit of a euphemism. I have heard that he could be quite bad-tempered and aggressive at times.

David: Yes, that’s true, but I just think that this was part of his teaching method. Some people need to be shaken up a bit, and shouting at them is one way of doing it.

I remember one woman asking him, rather innocently, ‘I thought enlightened people were supposed to be happy and blissful. You seem to be grumpy most of the time. Doesn’t your state give you perpetual happiness and peace?’

He replied, ‘The only time a jnani truly rejoices is when someone else becomes a jnani’.

Harriet: How often did that happen?

David: I don’t know. That was another area that he didn’t seem to want to talk about.

I once asked directly, ‘How many people have become realised through your teachings?’

He didn’t seem to welcome the question: ‘What business is that of yours?’ he answered. ‘How does knowing that information help you in any way?’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘depending on your answer, it might increase or decrease my level of optimism. If there is a lottery with only one winning ticket out of ten million, then I can’t be very optimistic about winning. But if it’s a hundred winning tickets out of a thousand, I would feel a lot better about my chances. If you could assure me that people are waking up here, I would feel good about my own chances. And I think feeling good about my chances would be good for my level of earnestness.’

‘Earnestness’ was one of the key words in his teachings. He thought that it was good to have a strong desire for the Self and to have all one’s faculties turned towards it whenever possible. This strong focus on the truth was what he termed earnestness.

I can’t remember exactly what Maharaj said in reply except that I know he didn’t divulge any numbers. He didn’t seem to think that it was any of mine or anyone else’s business to know such information.

Harriet: Maybe there were so few, it would have been bad for your ‘earnestness’ to be told.

Harriet: Maybe there were so few, it would have been bad for your ‘earnestness’ to be told.

David: That’s a possibility because I don’t think there were many.

Harriet: Did you ever find out, directly or indirectly?

David: Not that day. However, I bided my time and waited for an opportunity to raise the question again. One morning Maharaj seemed to be more-than-usually frustrated about our collective inability to grasp what he was talking about.

‘Why do I waste my time with you people?’ he exclaimed. ‘Why does no one ever understand what I am saying?’

I took my chance: ‘In all the years that you have been teaching how many people have truly understood and experienced your teachings?’

He was quiet for a moment, and then he said, ‘One. Maurice Frydman.’ He didn’t elaborate and I didn’t follow it up.

I mentioned earlier that at the conclusion of his morning puja he put kum kum on the forehead of all the pictures in his room of the people he knew were enlightened. There were two big pictures of Maurice there, and both of them were daily given the kum kum treatment. Maharaj clearly had a great respect for Maurice. I remember on one of my early visits querying Maharaj about some statement of his that had been recorded in I am That. I think it was about fulfilling desires.