This is an article I wrote around the year 2000 for an audience that I assumed would know nothing about Ramana Maharshi or Tiruvannamalai. I never got round to publishing it. It covers a period of my life of which I have very fond memories.

In 1976 I traveled overland to India solely to visit the ashram of Ramana Maharshi, a famous saint who had lived, until his passing away in 1950, at the foot of the holy mountain of Arunachala in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. I went there with the intention of staying several months (I am still here twenty-four years later) but on my arrival I discovered that the ashram I had traveled so far to visit only permitted new visitors to stay for three days. When my time was up, I looked around for somewhere else to live. There wasn’t much to choose from, so after a couple of hours I settled for a nice furnished room in a house that had about half an acre of tree-filled garden. The rent was (eat your heart out first-world city slickers) sixty-six cents a month, a little pricey for that area at the time, but the privacy and the garden made it worth the extra cash.

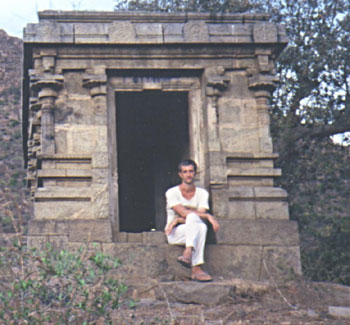

After a pleasant year and a half there, when I decided that the rent was making too much of a dent in my meager budget, I took a house-sitting job about a mile away. When the owner came back nine months later I again found myself looking for somewhere to stay. At that time I was feeling the call of the wild. I wanted somewhere remote where I could live and meditate quietly. The place that most attracted me was an abandoned temple, sited on a rocky outcrop at the base of Arunachala. I say it was abandoned because there was no deity there. Apparently, it had been stolen several years before. An empty lotus-shaped plinth marked the spot in the rear of the temple where the statue had once been worshipped. For me it was a case of location, location, location, and never mind the lack of amenities. It had no electricity, no plumbing, no door, the floor was covered with goat turds, the roof leaked (I discovered that later) and when I tried out the floor for size, I found I could only lie down, fully stretched out, if I positioned myself diagonally across the small rectangle that was the only flat space available. What it did have was a superb view across several miles of countryside, spectacular sunsets and an isolation that I thought would enable me to live and meditate in peace.

I engaged a couple a local carpenters to make me a burglar-proof door. Even though I owned virtually nothing worth stealing, I knew that security might be a problem in such an isolated area. All foreigners in rural India are assumed by some sectors of the community to be rich until a looting of their houses can prove otherwise, and even then there will be a deep suspicion that the valuable stuff is stashed elsewhere. A day or so later I moved into what I was already coming to regard as ‘my’ temple. I had never possessed real estate before. Owning a door in an abandoned shrine didn’t exactly make me a member of the landed gentry, but it definitely gave me the feeling that I had moved up into the propertied class.

There is a joke about Boulder (the new-age town in Colorado) that I love. ‘How many people from Boulder does it take to change a light bulb?’ Answer: ‘None. The people there just form a support group entitled “Coping with darkness.”‘

With no possibility to install electricity, I decided to cope with my own darkness by buying a kerosene lamp. I dealt with the absence of a toilet by digging a trench about thirty yards long in a nearby piece of land that had recently been reforested by the government. It was own personal and private contribution to the regeneration of India’s forests. Each morning I would squat there, have a shit, and cover it up with soil I had dug out of the trench. The next morning I would move a foot down the line. After a week or so of following this morning ritual, I noticed the undigested tomato seeds I had shat out were germinating in the trench. Three months later I had a line of plants thirty yards long, seedlings at the business end and fruiting plants at the other. I still remember the joy of picking and eating the first tomato off the first plant. It felt so organic, so ethnic.

When it came to water, I felt spoiled for choice. There was a small well about 200 yards away that supplied me with drinking water. A little further away a farmer was irrigating his fields with a diesel pump. I found out his watering times and had my daily bath there under a gushing fountain of water that shot out from his pump house about five feet above the ground. In this part of the world the temperature rarely drops below eighty degrees, even in midwinter, so afternoon cold showers are almost always a pleasure.

An extra five minutes’ walk took me to an artificial pond known as Unnamulai Tirtham. This could be translated as ‘The holy pond of the woman whose breasts have never been suckled’. The woman is Parvati, the female consort of Siva, who is the principal deity of most people in this area. The mountain of Arunachala, at the foot of which my shrine was located, is held to be a manifestation (not merely a symbol) of Siva Himself, and it is worshipped as such by millions of South Indians. Tirthams, by the way, are man-made structures that are designed to hold water for the use of passing pilgrims. In this part of the world they resemble inverted pyramids, with the steps on all four sides leading down to the water. Unnamulai Tirtham, which was fed and topped up by a seasonal stream that ran off the western slopes of Arunachala, was used both for bathing and for washing clothes. Other tirthams in the area were earmarked for drinking water, although one would need an iron constitution to sample them on a regular basis. They all tend to have a greenish, uninviting tinge.

Unnamulai Tirtham was by far the biggest tirtham in my area. When it filled with winter rains, it was big enough for me to swim eighty-yard laps. I swam there regularly in winter. It was good to keep moving once one immersed oneself in the water because the fresh-water crabs would nibble at any potential meals that hadn’t moved for a few seconds. Occasionally I would rest up on a little island, a rocky promontory that jutted out of the water, and admire the view.

Between the steps of the tirtham and the main pilgrim route around the mountain there was a magnificent granite building that was constructed many centuries ago. Once a year the deities in the principal temple of Tiruvannamalai were taken in a ceremonial procession around the eight-mile route that winds around the base of the hill. Every mile or so the procession would stop and the gods would be installed in temporary temples where the local people could come and worship them. This building was one of these temporary temples. Though it was only intended to be used for a few hours every year, it was a huge, imposing edifice. The British monarch has regional palaces that may only be used for a few days each year, but many of them are just as impressive as Buckingham Palace. Here Siva is king, and whenever he chooses to rest on his travels, the accommodation is always five-star.

Across the front entrance of this mantapam (that’s what Hindus call these buildings) there was finely chiseled frieze, carved out of local granite, that depicted various characters from the Hindu pantheon. The brick dome that surmounted it was beginning to crack, and the frieze was beginning to detach itself from the main wall. It looked as if it might crash to the ground at any moment, but there is a solidity to the sacred buildings here that can defy centuries of wear and tear. When I last looked at it a few days ago, it was still hanging there, still defying gravity.

Whenever I passed this mantapam I would look inside to check up on some small blue-gray owls that had taken up residence in niches in the wall about twelve feet off the ground. They would perch on the edges of their holes, even in broad daylight, with smug, self-satisfied looks on their faces that seemed to say, ‘I can see you but you can’t get near me’. I thought they looked cute and cuddly, but I’m sure the local rats and lizards had an entirely different perception.

I did my laundry in Unnamulai Tirtham every couple of days. Afterwards I would spread out my clothes to dry on the sun-warmed granite steps. Some of them seemed to have been made from recycled temple pillars. A few had carvings of couples coupling, writhing together in utterly improbable postures with rapturous expressions on their faces.

My clothes never took more than an hour to dry. While I waited I would watch the world go by. Farmers would bring their cows and buffaloes down a stone-paved ramp on one side of the tirtham and scrub them clean in the shallows. On the opposite side passing pilgrims would bathe and wash the clothes they were wearing. The women had a great technique for drying their six-yard or nine-yard saris. The woman who owned and generally wore the sari would drape the first two or three feet of wet cloth around her body. A second woman would hold the other end and the two of them would walk down the road together with the remaining yards of the wet sari stretched out tautly between them. It was a kind of mobile washing line strung between two walking women. The breeze and the hot sun would dry them in less than a mile.

Good detergent is a bit of a luxury for most Indian women. The vast majority of people here still dislodge the dirt from their clothes by soaking them in water and then repeatedly smashing them on rocks. A small amount of soap may be used, but the pounding is the main cleanser. This technique is a nationwide phenomenon and it apparently prompted Mark Twain, who passed through India about a hundred years ago, to wonder why so many Indians devoted so much time to trying to break rocks with wet rags.

On my way back to my shrine I would draw water from the first well and carry two full buckets home with me. That was more than enough for cooking, drinking and general cleaning. I used a kerosene stove to cook the provisions that I bought in Tiruvannamalai, a town located about four miles away.

About twice a week I would close my shrine and walk bare-footed around the mountain, following the same time-honored eight-mile circuit that the gods and the pilgrims took. Marker stones installed by a local emperor five hundred years ago to delineate the route can still occasionally be found by the side of the road. The walk is traditionally done in a clockwise direction, which means the ever-changing profile of the mountain is always on one’s right. As I passed through the town of Tiruvannamalai I would buy whatever I needed for the next couple of days and carry it home with me. I loved the walk; I loved the sights and the sounds of rural India and, since I was young, fit and healthy, the four-mile walk home with my shopping never felt like a burden.

The walk around Arunachala generally took me a little over three hours. If I stopped at any of the wayside shrines for a rest or had a drink in one of the many tea shops or coconut stalls that lined the route, I could add another half hour or so to my walk. I was never in any particular hurry. The local scripture that describes the merits to be gained by walking round the mountain declares that one should do the walk slowly, as if one were a ten-month-pregnant queen. Ramana Maharshi, the Hindu saint who drew me to India and brought me to this mountain, sometimes took three days to complete the walk. That was back in the 1920s, when most of the route passed through dense forest. In those days there was always the possibility of encountering a leopard or a panther on the way. By the 1970s the only predators left on the route were the professional beggars who would tug at one’s clothes as one walked along.

The circuit around Arunachala is deemed to be holy ground. Everyone walks the route without footwear, but this is not as tough as it sounds. Most westerners, who only ever walk without footwear on the beach, complete the route and experience nothing more than a mild soreness. If they do it again a couple of days later, usually there are no after-effects at all.

I abandoned footwear within days of arriving in Tiruvannamalai. I kept a pair of sandals handy for my rare visits to Madras, but in my first few years in India I doubt that I had anything on my feet for more than two days a year. Freed from the binding constraints of shoes and boots, my feet slowly expanded sideways. When I finally decided to wear shoes again (sometime in the 1980s, I think) I discovered that my width measurement was two sizes bigger than the length.

I also abandoned trousers. Most men in rural South India wear a dhoti, a single piece of cloth about five feet long that is worn as a wrap-around skirt. By the time I had lived in India for a year, I had given away all my old western clothes. My standard outfit was a white dhoti, a white banian and no shoes. Banians are Indian undershirts that resemble t-shirts, except that the neckline is a few inches lower. During my first year or so in India I only ever owned one dhoti at a time. When I lived in my sixty-six-cent-a-month room, I would take it off at night, wash it, hang it up to dry and put it on again the next morning. I remember that dhotis, which are made from thin woven cotton, lasted about four or five months. When they started to fray a bit or manifest stubborn stains, I would walk to town and buy another for about fifty cents. The old one would be recycled into handkerchiefs and household rags.

I had an English friend, Michael, who wore the same outfit. We arrived in Tiruvannamalai within months of each other, and both of us stayed for many years. His father had been a Conservative Party MP in Britain and his grandfather was a Scottish laird. Michael’s ancestral home was a castle on the Hebridean island of Mull. One evening he came to see me to tell me that he had been asked by his family to go to Bangalore to meet his grandmother who was touring Indian big-game parks. His mother had requested him to wear trousers because she didn’t want his grandmother to think he was a gone-native weirdo. Michael had also given all his trousers away, so he came to me in the hope that I might still have a pair somewhere. I didn’t, and nor did any of our friends. When I tell this story, few people find it more than mildly amusing, but at the time it provoked hysterical laughter in me. There we were, a group of foreign men, born and bred in the West, and not a single one of us could produce a pair of pants for a special occasion.