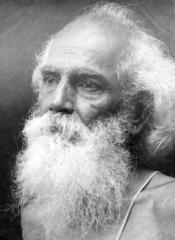

About ten years ago an Australian man at Ramanasramam asked if I would meet with a group of Australian devotees and talk to them about Ramana Maharshi. I agreed, but when I turned up, I discovered that it was going to be a formal interview with him, with the Australian devotees as an audience.

Our dialogue covered a wide variety of topics. Because the interviewer, John David, seemed to have very little knowledge of Bhagavan’s life or teachings, much of the interview was spent correcting many of the wrong ideas he seemed to have. When I read the transcript later, I realised that, serendipitously, this format of going back to basics and correcting his erroneous beliefs had turned the interview into an ideal presentation of the life and teachings of Bhagavan for people who knew little or nothing about them. For years I had it posted on my old site as a recommended read for people who were new to Bhagavan.

When the interview was over, John David told me that he didn’t accept my explanations of Bhagavan’s teachings on the mind. He wanted me to debate them publicly with a western vedantic scholar he knew, but I refused. Instead, I expanded the edited transcript of our conversation by several pages in an attempt to convey a more detailed presentation of what Bhagavan’s teachings on the mind really were.

This, then, is the edited and expanded version of our original dialogue. Ten years on, I still feel that it serves as an ideal introduction for people who want a summary of Ramana Maharshi’s life and teachings.

John David: Can you begin by telling us something about Ramana Maharshi’s early life? How he woke up as a young boy in Madurai.

David Godman: His given name was Venkataraman and he was born into a family of South Indian brahmins in Tiruchuzhi, a small town in Tamil Nadu. He came from a pious, middle-class family. His father, Sundaram Iyer, was, by profession, an ‘uncertified pleader’.

He represented people in legal matters, but he had no acknowledged qualifications to practise as a lawyer. Despite this handicap, he seemed to have a good practice, and he was well respected in his community. Venkataraman had a normal childhood that showed no signs of future greatness. He was good at sports, lazy at school, indulged in an average amount of mischief, and exhibited little interest in religious matters. He did, though, have a few unusual traits. When he slept, he went into such a deep state of unconsciousness, his friends could physically assault him without waking him up. He also had an extraordinary amount of luck. In team games, whichever side he played for always won. This earned him the nickname ‘Tangakai‘, which means ‘golden hand’. It is a title given to people who exhibit a far-above-average amount of good fortune. Venkataraman also had a natural talent for the intricacies of literary Tamil. In his early teens he knew enough to correct his Tamil school teacher if he made any mistakes.

After his father died when he was twelve, the family moved to Madurai, a city in southern Tamil Nadu. Sometime in 1896, when he was sixteen years of age, he had a remarkable spiritual awakening. He was sitting in his uncle’s house when the thought occurred to him that he was about to die. He became afraid, but instead of panicking he lay down on the ground and began to analyse what was happening. He began to investigate what constituted death: what would die and what would survive that death. He spontaneously initiated a process of self-enquiry that culminated, within a few minutes, in his own permanent awakening.

In one of his written comments on this process he wrote: ‘Enquiring within “Who is the seer?” I saw the seer disappear leaving That alone which stands forever. No thought arose to say “I saw”. How then could the thought arise to say “I did not see”.’

In those few moments his individual identity disappeared and was replaced by a full awareness of the Self. That experience, that awareness, remained with him for the rest of his life. He had no need to do any more practice or meditation because this death-experience left him in a state of complete and final liberation. This is something very rare in the spiritual world: that someone who had no interest in the spiritual life should, within the space of a few minutes, and without any effort or prior practice, reach a state that other seekers spend lifetimes trying to attain. I say ‘without effort’ because this re-enactment of death and the subsequent self-enquiry seemed to be something that happened to him, rather than something he did. When he described this event for his Telugu biographer, the pronoun ‘I’ never appeared. He said, ‘The body lay on the ground, the limbs stretched themselves out,’ and so on. That particular description really leaves the reader with the feeling that this event was utterly impersonal. Some power took over the boy Venkataraman, made him lie on the floor and finally made him understand that death is for the body and for the sense of individuality, and that it cannot touch the underlying reality in which they both appear.

When the boy Venkataraman got up, he was a fully enlightened sage, but he had no cultural or spiritual context to evaluate properly what had happened to him. He had read some biographies of ancient Tamil saints and he had attended many temple rituals, but none of this seemed to relate to the new state that he found himself in.

John David: What was his first reaction? What did he think had happened to him?

David Godman: Years later, when he was recollecting this experience he said that he thought at the time that he had caught some strange disease. However, he thought that it was such a nice disease, he hoped he wouldn’t recover from it. At one time, soon after the experience, he also speculated that he might have been possessed. When he discussed the events with Narasimhaswami, his first English biographer, he repeatedly used the Tamil word avesam, which means possession by a spirit, to describe his initial reactions to the event.

John David: Did he discuss it with anyone? Did he try to find out what had happened to him?

David Godman: Venkataraman told no one in his family what had happened to him. He tried to carry on as if nothing unusual had occurred. He continued to attend school and kept up a veneer of normality for his family, but as the weeks went by he found it harder and harder to keep up this façade because he was pulled inside more and more. At the end of August 1896 he fell into a deep state of absorption in the Self when he should have been writing out a text he had been given as a punishment for not doing his schoolwork properly.

His brother scornfully said, ‘What is the use of all this for one like this?’ meaning, ‘What use is family life for someone who spends all his time behaving like a yogi?’

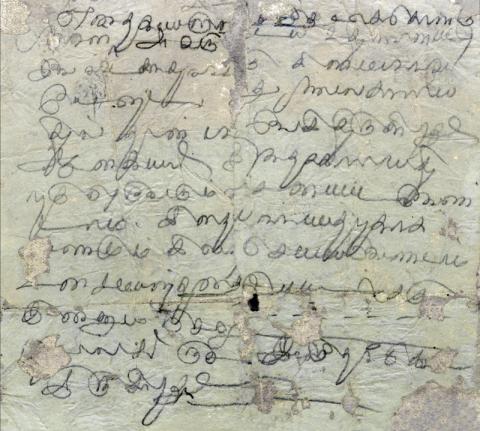

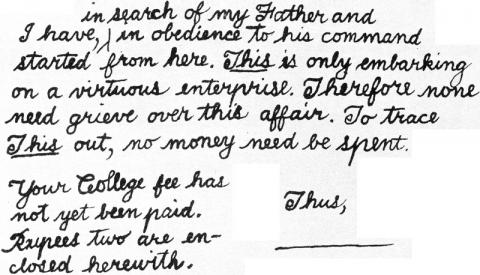

The justice of the remark struck Venkataraman, making him decide to leave home forever. The following day he left, without telling anyone where he was going, or what had happened to him. He merely left a note saying that he was off on a ‘virtuous enterprise’ and that no money should be spent searching for him. His destination was Arunachala, a major pilgrimage centre a few hundred miles to the north. In his note to his family he wrote, ‘I have, in search of my father and in obedience to his command, started from here’. His father was Arunachala, and in abandoning his home and family he was following an internal summons from the mountain of Arunachala.

He had an adventurous trip to Tiruvannamalai, taking three days for a journey that, with better information, he could have completed in less than a day. He arrived on September 1st 1896 and spent the rest of his life here.

John David: For someone who doesn’t know much about Arunachala, could you paint a picture of what this place is like, and what it signifies? Perhaps also say what it would have been like when Ramana Maharshi first arrived.

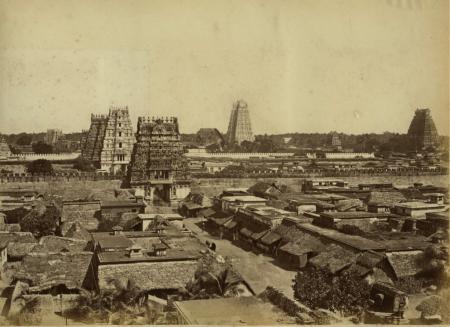

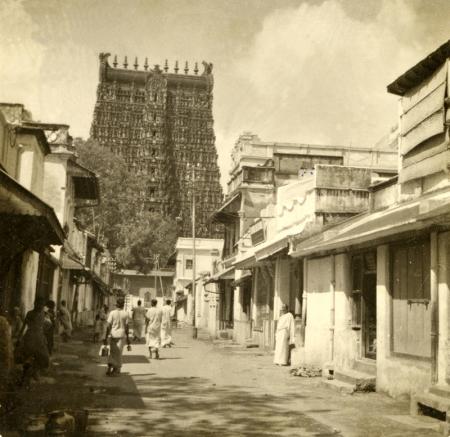

David Godman: The town of Tiruvannamalai, with its associated mountain, Arunachala, has always been a major pilgrimage center. The town’s heart and soul haven’t changed that much in recent times despite the presence of auto-rickshaws, TV aerials and a vast expanse of suburbs. The basic culture and way of life of people in Tiruvannamalai have probably been the same for centuries. Marco Polo came to Tamil Nadu in the 1200s on his way home from China. His description of what people were doing and how they were living are very recognisable to people who live here today.

Tiruvannamalai has one of the principal Siva-lingam temples in South India. There are five temples, each corresponding to one of the elements: earth, water, fire, air and space. Tiruvannamalai is the fire lingam. The earliest records of this place go back to about AD 500, at which point it’s already famous. Saints were touring around Tamil Nadu in those days, praising Arunachala as the place where Siva resides, and recommending everyone to go there. Before that, there aren’t really any records because local people didn’t start writing things down or making stone buildings that would last. There’s a much older tradition that suddenly appears in the historical record about 1,500 years ago, simply because a major cultural change resulted in people making proper monuments and writing things down. I would say that Ramana Maharshi was, in this historical context, the most recent and probably the most famous representative of a whole stream of extraordinary saints who have been drawn by the power of this place for at least, I would guess, 2,000 years.

John David: When was the big temple built?

David Godman: It grew in layers, in squares, from the inside out. Once upon a time there was probably a shrine about the size of a small room. You can date all these things because the walls of temples here are public record offices. Whenever a king wins a war with his neighbour, he gets someone to chisel the fact on the side of a temple wall. Or, if he gives 500 acres to someone he likes, that fact also is chiselled on the temple wall. That’s where you go to see who’s winning the battles and what the king is giving away, and to whom.

The earliest inscriptions, they’re called epigraphs, on the inner shrine date from the ninth century, so that’s probably the time it was built. Progressively, up to about the 1600s the temple got bigger and bigger and bigger. It reached its current dimensions in the seventeenth century. For people who have never seen this building, I should say that it’s huge. I would guess that each of the four sides is about 200 yards long, and the main tower is over 200 feet high.

John David: And that’s where Bhagavan came to when he arrived?

David Godman: When Bhagavan was very young he intuitively knew that Arunachala signified God in some way. In one of his verses he wrote, ‘From my unthinking childhood the immensity of Arunachala had shone in my awareness’. He didn’t know then that it was a place that he could go to; he just had this association with the word Arunachala. He felt, ‘this is the holiest place, this is the holiest state, this is God himself’. He was in awe of Arunachala and what it represented without ever really understanding that it was a pilgrimage place that he could actually go to. It wasn’t until he was a teenager that one of his relatives actually came back from here and said, ‘I’ve been to Arunachala’. Bhagavan said it was an anti-climax. Before, he had imagined it to be some great heavenly realm that holy, enlightened people went to when they died. To find he could go there on a train was a bit of a let down. His first reaction to the word Arunachala was absolute awe. Later there was a brief period of anticlimax when he realised it was just a place on the map. Later still, after his enlightenment experience, he understood that it was the power of Arunachala that had precipitated the experience and pulled him physically to this place. The verse I just quoted from chronicles the early stages of his relationship with the mountain:

Look, there [Arunachala] stands as if insentient. Mysterious is the way it works, beyond all human understanding. From my unthinking childhood, the immensity of Arunachala had shone in my awareness, but even when I learned from someone that it was only Tiruvannamalai, I did not realise its meaning. When it stilled my mind and drew me to itself and I came near, I saw that it was stillness absolute.

The last line contains a very nice pun. Achala is Sanskrit for ‘mountain’ and it also means ‘absolute stillness’. On one level this poem is describing Bhagavan’s physical pilgrimage to Tiruvannamalai, but in another sense he is talking about his mind going back into the heart and becoming totally silent and still. When he arrived, and this is something you won’t find in any of the standard biographies, he said he stood in front of the temple. It was closed at the time, but all the doors, right through to the innermost shrine, spontaneously opened for him. He walked straight in, went up to the lingam and hugged it. He didn’t really want this version of events publicised for two reasons. First, he didn’t like letting people know that miracles were happening around him. When such events happened, he tried to play them down. Second, he knew that the temple priests would get very upset if they found out that he had touched their lingam. Even though he was a brahmin, the temple priests would take his act to be a contaminating one, and they would have had to order a special elaborate puja to reconsecrate the lingam. Not wanting to upset them, he kept quiet.

John David: Yes, we’ve just come from the temple just now and there’s a huge lock on the door.

David Godman: Yes. Ordinarily, no outsider can get anywhere near the lingam. Looking after it is a hereditary profession. No one from outside this lineage is allowed over the metal bar that is about ten feet in front of the lingam. There is another interesting aspect to this story. From the moment of his enlightenment in Madurai there was a strong burning sensation in Bhagavan’s body that only went away when he hugged the lingam. Touching the lingam grounded or dissipated the energy. The lingam in the temple is not just a representation of Arunachala. It is held to be Arunachala himself. The hugging of the lingam was the final act of physical union between Bhagavan and his Guru, Arunachala. I have not read of any other visit by Bhagavan to the inner shrine. This may have been the only time he went. One visit was enough to transact this particular piece of business.

Bhagavan always loved the physical form of the mountain Arunachala and spent as much time as he could on its slopes, but his business with the temple lingam was completed within a few minutes of his arrival in 1896.