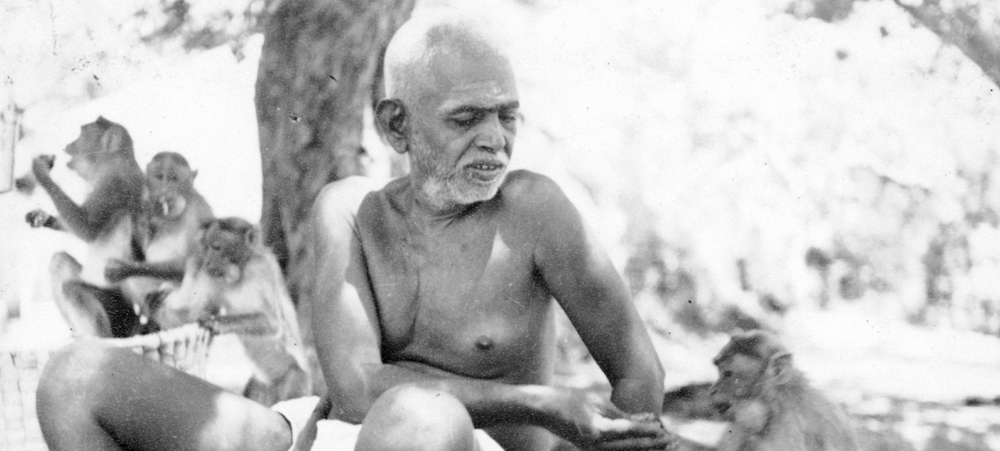

I was hunting up some references in The Call Divine when I came across a long section in a 1955 issue entitled ‘Symposium: Bhagavan Sri Ramana as I knew him’. The editor, Swami Rajeswarananda, had written to many devotees who had had personal contact with Bhagavan and asked for their recollections of the time spent in his presence. Many people responded, enough to fill almost one hundred pages of the January 1955 issue. I think this was probably the first attempt to collect and publish an anthology of accounts of people who had been affected by Bhagavan.

I went though it and found many fascinating narratives, some of which I had not come across before. Many familiar names were there, along with some I had never heard of. I am presenting a selection of the accounts here.

Since the style and the language were often of a very poor quality, I have rewritten and edited almost all of the accounts. The order in which the accounts appear is the same as in the original anthology.

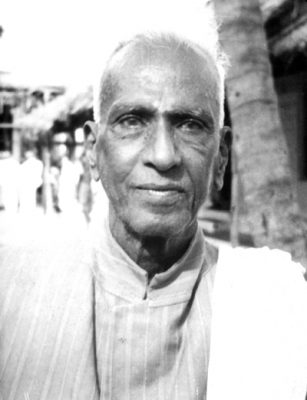

Sri Devaraja Mudaliar, Sri Ramanasramam

It was in 1900 that I first cast my eyes casually on Bhagavan. From 1914 on I began visiting him, though my visits were few and far between. It was not till 1933 when I had my first great adversity that, true to the old adage, Bhagavan, our God, got his opportunity.

From that time on I came more and more under his spell, got to know him better, and as a result have stuck to him for ever. In this long interval between 1933 and his samadhi in 1950 I am vain enough to imagine it has been given to me to know so much of him. It would be difficult to press it all into the compass of a small article, as a contribution to a symposium must necessarily be. However, I must try and do my best.

The first thing that was borne in upon me, which subsequent closer acquaintance has thoroughly confirmed, was the fact that Bhagavan was no more anxious to annex any devotee who came to him than the devotee was fit to be annexed. Even to draw me nearer his spell took him nearly twenty years. He waited for time and circumstances to make me ready for him. In my long connection with him I have discovered this is one of his traits, whether you hold to it to his credit or otherwise. Kavyakanta Ganapathi Sastri was so advanced in mantra japa, tapasya, and had great devotion to Bhagavan. Bhagavan, in return, had great respect for him and showed him great consideration. But even in a case such as this, Bhagavan did not go out of his way to ripen him before his time was due. He was content to wait for the right moment.

I have heard that when, after the Sastriar’s passing away, Bhagavan was asked whether, in his case, there was likely to be liberation from all further births. He replied, ‘How could it be? He had such a strong desire for more powers?’

However, it was well-known that this great person desired powers not for selfish purposes, but for the regeneration of the world and its betterment.

This characteristic of Bhagavan is not to be wondered at. Tagore sings, ‘Time is endless in thy hands, my Lord. Thou knowest how to wait. Thy centuries follow each other, perfecting a small wild flower.’

The reader should not, however, run away with the impression that Bhagavan does nothing. On the contrary, he does everything, each act in its own proper time, as he alone knows best. In the worst years of my domestic grief, which occurred at the same time as the end of my professional success, Bhagavan was a source of help and strength, past all description. In that period, a devotee, well known in ashram circles as Thiruppugazh Alamelu, was singing before Bhagavan a song from Bharathi’s ‘Kannan Pattu’, but substituting the name Ramana for Kannan. I felt then, and feel even more so now, that all that is said therein of Krishna is true of Bhagavan. The poem says:

If he wants to initiate a soul in the path of perfection, he can do it in a word. He will tell us how to overcome karma and get on in life. When earnestly sought for, he will come without a moment’s delay and without pretexts for holding off. To me, he is what the umbrella is against rain and food against hunger. He will give me money whenever I ask for it. Bear and forbear even when I scoff at him. Console me with dance and song and know without my telling him what is my heart’s desire. Among all saints, where is there one so kind? If I get conceited, he will bring me to my senses by sending a severe blow. He will contemptuously turn away from anything said in hypocrisy. In times of depression his words of grace will flood our soul with light and cheer. When we have our quarrel with him and feel he has neglected us, he will do something to gladden our heart and fill it with gratitude. When we are in great peril, he will come and stand by us and avert the catastrophe. By his grace all evils will be consumed like moths in a flame.

From my experience and also the experience of some other devotees I can affirm all this of Bhagavan, though it must perhaps be added that such things happen to Bhagavan’s devotees more in the earlier stages of their affiliation with him than in the later years, after they had become seasoned followers. Has he not himself exclaimed in the first of his Five Hymns to Arunachala:

You showed your heroic prowess, but having subdued, you do nothing at all now, O Arunachala.

This is not to say that nothing bad or painful will ever happen to a devotee. There would still be cases where some calamity, disaster, sickness or pain has to come, as per one’s prarabdha, which it would not be proper even for great souls such as Bhagavan to prevent altogether. In such cases I have found Bhagavan greatly softens the blow, or at the very least grants all help and resources in various ways so as to enable the devotee concerned to tide over the crisis and bear it easily. I have seen all this happen in my own case, as well as in the case of others. Even now I am just passing through the effects of a small mishap which befell me recently. But while the mishap had to come, Bhagavan has seen to it that it came at a time and place, and under circumstances which were the best for one in my position to face.

Once when I asked Bhagavan how, in answer to our earnest prayers to him for help, we get relief, seeing that he has no mind which can desire to send us the required relief, he was pleased to say, ‘All will still happen. It will happen automatically.’

There is another trait that I have observed in Bhagavan. Though he was equally accessible and kind to all alike, and though thousands of visitors came and went over the years, there was a small coterie of followers among all this crowd whom he definitely took over for his special care. Here again it must be said that he was not making any choice, for where was there a mind in him to make a choice? Such things were happening automatically. However, to all alike he was immeasurably kind.

Now I must draw attention to another characteristic of Bhagavan. He was extremely humble, affable and accessible, and yet kept all at a distance. There was a royal dignity that clothed the naked Bhagavan, and few could ever allow themselves to forget it. Also, even in his kindest and most indulgent moods, even in dealing with children or grown-up children (which some of his disciples like me were), he would never make a concession in stating the truth or advising its pursuit. Kind and loving as he undoubtedly was, he was, unlike some saints, more the strict father than the indulgent mother. I myself used to call him my father-mother in all my letters to him. Whenever anyone used to sing a Tamil song in which that phrase occurred, Bhagavan would look at me and smile. I mention this here merely to illustrate what great attention he was always paying to his devotees.

I wrote of Alamelu Ammal and the Kannan song she used to sing. About two years before Bhagavan’s mahasamadhi, after she had passed away, somebody came and sang that song. Bhagavan said ‘Alamelu used to sing that song’. While apparently indifferent to the hordes who came and went, he was really closely attentive to all that was happening, and helping wherever he could. Bhagavan has himself said that as soon as someone appears before him, that person was an open book for him. Nothing about us was hidden from him.

Though Bhagavan’s main teachings are well known and need no further publicity, I shall refer briefly to them here. His whole teaching was succinctly expressed in the biblical quote, ‘Be still and know that I am God’. That is to say, one should attain quiescence or real mauna and realise the Self that is within each of us as ‘I am’. To attain this state of thoughtlessness Bhagavan asked us to concentrate on the question ‘Who am I?’ He wanted us to find the source of this I-thought, which is the root of all other thoughts. Through this enquiry, he said, the individual ‘I’ will disappear and the Self will emerge. Though Bhagavan always said this vichara method was the best, he almost always added, ‘If you say this method is too hard for you, or if you are too weak to follow it, you had better completely surrender to God. The same result will follow.’

Thus he advocated the bhakti method almost in equal measure, saying that the bhakta will eventually come to realise there is only the Self and not a dichotomy of God and devotee. I never, however, saw Bhagavan recommend either the karma yoga or raja yoga methods.

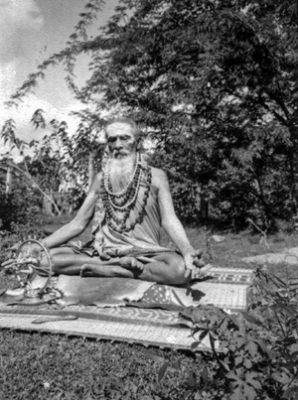

Yogi Shuddhananda Bharati, Yoga Samaj, Vadalur

November 20th: Krithikai Day. The ashram is busy with the pouring crowds. Bhagavan is sitting outside his cottage. The ashram was then just a cottage of thatched leaves. I was sitting inside. I did not stir from my perch from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. Even the call for food did not shake me. My friends had come that day to take me to Pondicherry. I was rather unwilling to leave the presence of this dynamic force. I could not even open my lips for permission. For my mission and its fulfilment were clear before me. I was hanging and swinging between ‘this’ or ‘that’, ‘here’ or ‘there’. My friends sat before me putting questions to me. Silence was my answer. They went to Maharshi and rolled out their conundrums. Silence was the answer. We were in silent heart-to-heart communion as my friends pestered him.

What is the good of remaining mum like this? What is the goal of man? What is God? What is ‘I’? Why are we born? How to get swaraj [self-rule] for the country? Violence or non-violence? What is Vedanta? What is Siddhanta? What is the meaning of the Vedas? A series of serried questions and a cascade of thrilling silence followed. One self-sufficient man lost his patience; he was a follower of modern education. His brain was full with Kant and Descartes. He had very poor opinion about our Sankaras and Gaudapadas. He had more regard for hatted and booted western armchair philosophers than for realised bald heads.

He hurried up to me and remarked, ‘Swamiji, you, as a well-educated man, must not be like this. You must be more like Bergson, Berkeley, Jung, Huxley. You must go to America and London and acquire name and fame.’ My reply: silence.

At this time Maharshi rose up and came inside. The crowd was melting away for supper. The evening was solemn. Maharshi sat quite near me. I touched his feet, and then caught hold of his hands. His force was flowing into me. I saw his eyes; for Maharshi to me was his vision in and out. I saw the fire of knowledge radiating from those two red binocular-like eyes that saw the world around like a cinema show. His eyes darted into me. Tears flowed from my eyes. I did not move my tongue. Maharshi was reading my heart and mind, which were being saturated with divine consciousness. Silence for five minutes.

Then Maharshi spoke out in a calm, mellow, silvery voice: ‘Bharathi, take refuge in silence. You can be here or there or anywhere. Fixed in silence, established in the inner I, you can be as you are. The world will never perturb you if you are well founded upon the tranquility within. You have a sankalpa – to write out your inspirations, to bring out the Bharata shakti [power of India]. It is better to finish off sankalpas here and now and keep a clear sky within. But do it in silence. Gather your thoughts within. Find out the thought centre and discover your Self-equipoise. In storm and turmoil be calm and silent. Watch the events around as a witness. The world is a drama of gold, women, desire and envy. Be a witness, inturned and introspective.’

I wept and mumbled, ‘Do you want me to remain?’ I felt I must come back the next day. Maharshi, after a deep silence, saw my face. After his gaze had sunk into me he whispered, ‘You must come back, and you will. For every one must come to this path. Wind wanders before returning to the silence of the akasa.’

‘Are you saying that I will not return in a week?’

Maharshi smiled now and said, ‘Why a week? Even after years you must come here. Only take refuge in silence. Allow karma to work itself out and march on in faith. You will not miss the goal.’

With this he fell into trance while I fell at his feet. One hour passed. Then half an hour more. My philosophically inclined friend also stood there, struck dumb. His questions were rushed into silence. I placed a lump of dates into the hands of the Maharshi. He took a piece and returned the rest to me. I understood, ‘Today’s date is a sweet one. It is the date when I received the message of silence. I must taste in silence each date of my life by having communion with the divine.’

For two decades I was silence itself. Years later I returned. The former simple ashram had disappeared; the body of the Maharshi had disappeared. But the vibrating presence whispered into me ‘Silence, yet more silence!’

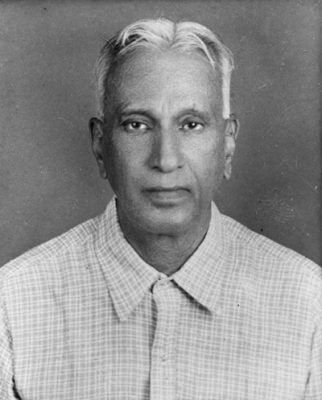

Prof. V. B. Athavale, M.Sc., F.R.G.S., Kirloskarwadi

I had the good fortune of meeting Sri Ramana Maharshi in April 1944 and observed for one week his state of supreme consciousness in which worldly knowledge appears insignificant and produces no worries.

When Paul Brunton asked, ‘Will the world soon enter a new era of friendliness and mutual help, or will it go down into chaos and war ?’ Maharshi replied, ‘There is one who governs the world. He knows how to look after it. He bears the burden of the world and not you.’

Maharshi’s reactions to my unspoken intentions were, however, very tender and marvellous. I reached his Tiruvannamalai ashram with my wife on 16th April. To investigate the relation between Gita and the Vedic literature with regard to the Vedic quotations explicitly referred to by Maharshi Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa, (the author of the Gita) I had prepared a genealogical chart of some 350 persons mentioned in the Rigveda. I intended to show this chart to Sri Ramana Maharshi and talk to him about my Gita study. But when I found that no one talked in the hall, I dropped the idea and decided not to talk about it unless the Maharshi showed some interest himself.

Next day, when I entered the hall at 8 a.m., I was surprised to find that the Maharshi had asked Mr Iyer to hand over a Gita book to me that contained 746 verses instead of the normal 700. Mr Iyer had also been asked to get my opinion on this difference. Thus I got the chance of opening the Gita topic. To avoid disturbing the peace in the hall, Maharshi asked me to meet a pandit that afternoon to talk about the Gita. The pandit was going to relay our discussion to the Maharshi later. I ended up talking to this pandit for four days.

Maharshi eventually saw my genealogical chart and asked me, via the pandit, what I had to say about ‘tenaiva rupena chaturbhujena’, the reference to the four hands of Krishna in the 11th chapter. I explained to him that Arjuna has addressed Krishna twice as ‘Vishno’ in the 11th chapter. In the 10th chapter we are told that Krishna was Vishnu out of Adityas. Though this expression is usually interpreted to mean the sun in the twelve signs of the zodiac, it cannot be correct. Because, the next words say ‘I am the sun among the stars’. The Rigvedic expression ‘Astau putraso Aditeh’ tells that Aditi had eight sons and Adhvaryu Brahmana tells that Vishnu was one of the eight sons of Aditi. Yajurveda states, ‘Narayanaya vidmahe Vasudevaya dhimahi tanno Vishnuh prachodayat’. It means that Vishnu was called Vasudeva patronymically. Thus Krishna and Vishnu had the identical name Vasudeva patronymically.

According to old traditions Vishnu holds in his four hands (1) Shankha, (2) Chakra, (3) Gada, (4) Padma. Krishna had in his normal two hands the famous panchajanya conch and the reins of the four horses. Arjuna first saw the four-handed form of Vishnu. Hence the 17th verse mentions only ‘gada’ and ‘chakra’ to be the two weapons, which were not in the hands of Krishna. The Mahabharata states that Krishna had decided not to wield any weapon in the war. In verse 44 Arjuna says, ‘I am terrified by this thousand-fold form. Please show me your original form with four hands. Verse 45 again mentions the same two weapons ‘gada’ and ‘chakra’. Verse 51 refers to the normal human form of Krishna.

Maharshi was pleased when he heard the explanation. He gave me his blessings for the study and suggested that I should write a commentary on the Gita. On 23rd April I was sitting as usual in the hall. One gentleman, who was sitting near me, was reading some English passage from a book in a loud whisper. I heard the sentence, ‘A siddha is inferior to a conjuror’. I thought that the author of the sentence had committed a mistake, but didn’t intervene. On 24th April I went into the hall in the morning and informed Maharshi that I was leaving in the evening and requested him to give his autograph. The secretary told me that Maharshi never signed his name. I expressed regret for my ignorance of the rule and said that I merely wanted the handwriting of Maharshi and not his signature. The gentleman, whose sentence I had heard the previous day, was sitting near me. I was thinking of asking him the name of the author who had written that a siddha was inferior to a conjuror. I wanted to point out the mistake and demand its rectification.

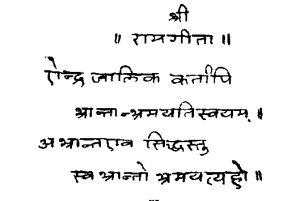

Meanwhile, Maharshi took a pen and a piece of paper in his hand and asked Mr Iyer to tell me that he was writing a reply to my query. Mr Iyer told me that my wish had been fulfilled and that Maharshi was giving his handwriting to me. The verse that Maharshi wrote was a reply to my unspoken query to the gentleman, as well as to my mental comments about the sentence I had heard.

The book which the gentleman was reading was the English translation of a Tamil rendering by Maharshi of an old Sanskrit poem, called Rama Gita. The verse says, ‘A conjuror deludes others by his tricks but he himself is never deluded. A siddha who manifests his siddhis is, however, deceiving others as well as deceiving himself.’

When Maharshi handed over the Devanagari script to me, a flash in his eye suggested that I was free to point out the mistakes of the author of the statement.

Dr Hafiz Syed, M.A., Ph.D., D.Litt., Allahabad

It was in March 1935 that a friend of mine, Mr. Bertram Keightly gave me a copy of A Search In Secret India by Paul Brunton. I devoured it, felt interested in Ramana Maharshi, and longed to meet him. The same year during the Christmas week I paid my first visit to Madras to attend the Theosophical Society convention. From there I went to Mysore in response to the invitation of Sir Mirza Mohd. Ismail. On my return to Bangalore I accidentally met Maurice Frydman. His ascetic life made me curious to know who he was and what made him lead an austere life. It was he who told me a great deal about Ramana Maharshi and roused my sleeping interest in him.

Through his good offices I arrived in Tiruvannamalai one morning and was ushered into Maharshi’s presence by Paul Brunton himself. After three days’ stay there, while taking leave of the Maharshi, I begged him to give me his ashirvad [blessings] before I left him. He was gracious enough to nod his assent, which meant a great deal to me.

Next year, 1936, I visited him again during Dassara holidays. In 1937, the most momentous year in my life, I was attacked by a series of misfortunes. I had to stay in one of the rooms in the ashram itself for more than a month on account of a serious illness. It was during those days that I realised vividly his greatness as a divine man who was endowed with all spiritual and human qualities. While I was lying ill with a high fever, Maharshi was considerate enough to visit me three times and prepared upma [wheat porridge] for me with his own hand. My eyesight was affected by the high fever. When parting with him to start for Madras for treatment, I took hold of his toes and touched my eyes with them. For me, that was a sufficient guarantee that my eyesight would not fail me. So it has not. I shall never forget the grace he gave me during my serious illness. I had no idea what it was till I returned to my place in North India and felt its purifying effect on my life. I never felt so light and free from all taint of desire as I did in those days.

In 1939 I went on a sacred pilgrimage to him during the summer vacation. As there was a big crowd in the ashram, I could not take leave of Maharshi before leaving Tiruvannamalai. The result was that, somehow or other, I was deprived of the inestimable privilege of having Maharshi’s darshan for three years. From 1943 onwards I never let a year pass without visiting him. I was present during his final illness and saw him undergoing an operation for sarcoma without any sigh, shriek or anaesthetic. The doctors were amazed at his composure and an unheard-of peace of mind.

During his serious illness he was so considerate and thoughtful of the feelings of others that, despite his intense suffering, he did not deprive any one of the privilege of having his darshan. His sense of humanity was as great as his sense of spirituality.

Once, during one of his birthday celebrations, I read out an article in the hall that contained the statement, ‘The more a person is spiritual, the more he is human’. I asked about this, and he agreed that it was true. The sight of suffering, or a mere tale of it, touched his heart.

I invariably noticed during my close contact with him that he was indifferent to his body, as he believed that it was transitory. The real in him, and in others, was beyond any change.

One of the plainest teachings he gave to seekers of truth was self-surrender to God or Guru. He recommended it because he himself had surrendered himself to the divine and reaped its fruit. This method of approach to truth, he said, was the easiest and the safest if one had an earnest desire to attain liberation. I have often felt strongly that his method of approaching truth was so definite, clear and direct, it must appeal to the modern mind because it is essentially scientific. Maharshi never expected anyone to pin his faith in any particular scripture, or practise any sadhana, or repeat any mantra. All he expected of us was to closely and critically analyse the content of our own being, to discover what we really were to see if there was any thing in us which survived the decay of our bodily frame. His words went straight into our heart because he lived what he taught. His grace was ready for those who were ready for it; in other words, those who had made themselves fit recipients of his grace.

The dominating feature of his philosophy was the unity of life, the oneness of the divine essence which is the indwelling Self of all. In view of this deep-seated conviction of his, we noticed that he made no distinction in everyday life between great and small, rich or poor, holy or profane. He treated all alike. He habitually saw the one life vibrant in all. Another remarkable and distinguishing feature of his life was that he showered grace on every one whom he considered eligible for it, whether they were frequent visitors to his ashram and attached to him or not. Those who came from other ashrams and were the disciples of other Gurus received the same transmissions of grace, if they were ready.

I heard him repeatedly say that there is one who governs the world and that it is his task to look after the world. He who has given life to the world knows how to look after it also. It is he and not us who bears the burden of the world. He would also say that each was helped according to his nature, in proportion to his understanding and devotion.