By Smt. Padma Venkataraman

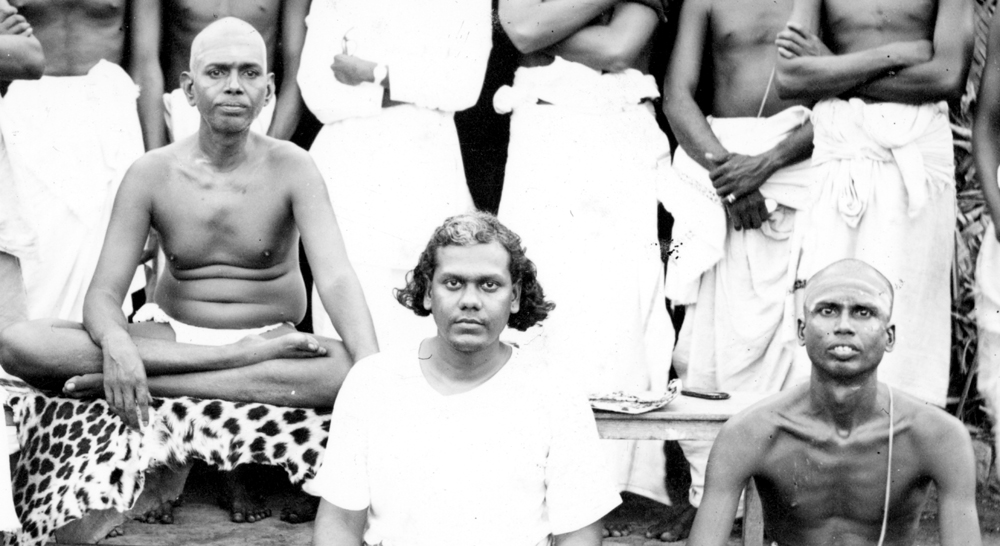

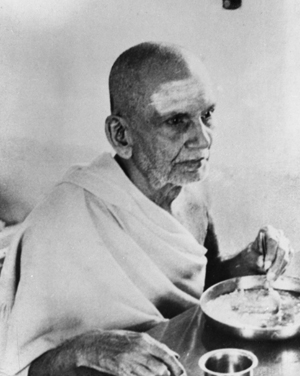

Padma Venkataraman had the good fortune both to serve Muruganar and be taught Bhagavan’s teachings by him. This account of her years of association with Muruganar has been taken from Ramana’s Muruganar a book brought out in 1992 by the Ramana Maharshi Centre for Learning, Bangalore, to commemorate the centenary of Muruganar’s birth.

* * *

1947 is a memorable year in Indian history as the year of Independence. That year is an unforgettable one in my personal life too. My husband took me to Bhagavan and that opened up an altogether new chapter in my life. By the grace of Bhagavan I had the rare good fortune of being able to serve Muruganar Swami. I developed a deep devotion for him on hearing about his supreme state from inmates of the ashram, and by reading Ramana Sannidhi Murai. I used to visit him often and seek clarifications from him about his works.

Muruganar had lost his separate identity in Bhagavan. He would not accept any other God except Bhagavan. He was the very picture of humility.

On many occasions during my visit to his house I would notice that the eatables, fruits and even medicines lay untouched.

If I asked, he would say, ‘Amma, I forgot’.

He had no consciousness of the body, nor a sense of time. His only feast was to enjoy the beauty of Ramana in a thousand and one ways through his poetry. I used to pray to Bhagavan that I could have the opportunity to serve this unique sage. Soon I was blessed with such a chance.

I would set the songs of Ramana Sannidhi Murai to music and sing before him. He would not tolerate any mistake and would advise that one should sing the words with clarity and perfection. While hearing the songs on Bhagavan, he would simply lose himself. Tears would flow involuntarily. He would give vent to his feelings by writing more poems in a continuous unbroken chain.

Somasundaram Pillai and his family had great regard and affection for Muruganar and would send food for him. Then they had to leave for some time for Cuddalore. At that time I was staying in the outhouse of Manavasi Ramaswany thatha. He too was deeply attached to Muruganar, so he took on this responsibility of feeding him. In the mid-afternoon Muruganar would come for bhiksha in the scorching sun. I could not bear the sight and would be moved very much. Once the wife of thatha [who did the cooking] had to go out of town. I requested him not to inform Muruganar for he would then stop coming. I took over the cooking and prepared several tasty dishes for him the next day.

Muruganar came as usual. He was brought to the outhouse where I was staying. I heard his voice asking for bhiksha. When I came out I saw him standing there, full of luster. I had brought the various dishes which I had prepared. Muruganar asked me to put all the items together in a towel which he had brought. What a difficult situation! I had prepared dishes with different tastes, but he, the jnani without any attachment, seemed to treat all items as one. What a difference between our attitudes and his!

I decided that he should not be troubled any further to come for food in the hot sun. I felt that I should somehow take the food to him personally. So thinking, I went to his place and pleaded for his permission. I would not budge till he gave his consent to my serving the food at his place.

He remarked, ‘I am noted for my stubbornness. You beat me hollow.’ But he finally agreed.

I used to go regularly to his house with the dishes and serve him at a time convenient to him. The thought that this privilege would be lost to me if aunt [thatha’s wife] returned nagged me. I found a way out. I told Muruganar that out of consideration for the old age of the aunt, I should be allowed to take over. He could not refuse when it was put that way. I managed to convince thatha also with the same reasoning. Thus I had the opportunity of serving Muruganar for several months.

Bhagavan’s health started deteriorating. Muruganar could not bear this. He would submit each day a song ending with the words ‘live for a hundred years’. Bhagavan would scrutinise these verses. Muruganar asked me to sit in front of the devotees in Bhagavan’s presence at 6.30 in the evening regularly [and sing these compositions]. I was only too happy to do so. The old devotees like T. P. R., Toppiah Mudaliar and K. K. Nambiar would be particularly moved. At the request of Janaki Matha’s group, I would sing the songs again outside the ashram.

The song for that day would be given to me in the afternoon. I would read it before Muruganar to avoid mistakes while singing in the evening. On the fourth day I made a mistake while reading it. The words were ‘Oonamara nooru andu vazh’ meaning ‘live healthily for a hundred years’. I read it as something else. I do not recall the exact mistake I had made. Muruganar was irritated.

He asked me, ‘Are you reading the one composed by me, or have you written something yourself?’

I felt bad at making a vital mistake and left immediately, after prostrating to him. However, that evening I sang the venba [verse] without any mistake. After coming out I asked Muruganar if my rendering was alright.

‘Yes, yes, it was fine,’ he said. I am sure it was only due his grace.

In one of the songs he had referred to Bhagavan as ‘Jnanabhandara nayaka’ – ‘custodian of the treasury of jnana’. I read it as ‘bokkisham’, also meaning ‘treasury’. Immediately Bhagavan noticed the mistake and enquired through the attendant Sathyananda Swami if Muruganar had used those words. Bhagavan knew so perfectly Muruganar’s style of writing.

As Bhagavan’s mahasamadhi approached he gave up all food and lived only on kanji. That too was practically stopped towards the end. All this distressed Muruganar. When Bhagavan attained mahasamadhi, Muruganar could not control his grief. He rolled on the ground unable to contain his sorrow. The pain of physical separation was too much for him to bear. Other devotees like Premji had to somehow console him. It was not that Muruganar was unaware that Bhagavan’s presence envelops the entire universe. Yet such was the physical intimacy, the cutting of the bonds made him inconsolable.

After Bhagavan’s mahasamadhi most of the devotees left the ashram for pilgrimages to different sacred places associated with Siva. Muruganar was taken to Melaisivapuri by the devotee Chettiar. Kanaka and I also went to sacred places. When I returned alone after some months, I could not find any suitable place to stay. The ashram authorities permitted make to occupy a room in Dr T. N. K.’s house where Muruganar used to stay. I was given the room adjacent to his. They had locked up his belongings in a room. What belongings? Just one bench and a bundle of books.

Suddenly one day a devotee came and cleared up Muruganar’s room, saying that he was returning. I was simply delighted. This would give the rare opportunity of serving him again, this time at close quarters, and to learn about Bhagavan’s teachings directly from him. What can I say? Surely, it was only the showering of grace on me by Bhagavan.

Muruganar Swami came the next day. I had prepared food for him that day. He agreed to take it but added, ‘Do not cook for me from tomorrow. Everything will happen as it should.’

It is difficult to describe how heart-rending these words were. Somehow I managed to gather courage and told him, ‘How can I stay in the next room and yet not serve you?’

Muruganar relented.

‘All right. I give consent only subject to one condition. Some lady should sleep with you at night.’

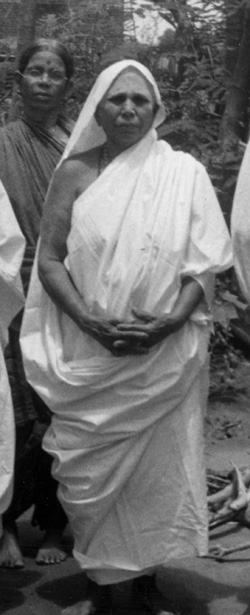

Then I was only twenty-two. I was moved by his concern for me. It was like a mother keeping a watchful eye on her grown-up daughter. In those days water was quite a problem. The houses were not near either. I requested Shantammal Granny to sleep with me. Fortunately, she said ‘Yes’.

On the days she could not come I would close my room by 6.30 at night and go to her house. Once she absented herself without notice. I was also sick but did not wish to show it lest the swami should refuse permission for me to cook. I kept waiting but Santammal did not come. I had no choice except to brave it in the dark. So I started.

But hardly had I stepped forward a few steps when an old lady accosted me and asked, ‘Where is Dr T. N. K’s house? I came to the ashram but I was told I could not stay after nightfall. Seeing that I could not walk a long distance, they suggested that I could sleep for the night in T. N. K’s house.’

Even I recall this incident now, I am thrilled to the core at the thought of the invisible and constant protection of the swami.

Swamini Anantammal, Smt. T. K. Duraiswami Iyer, Kanakamma, other devotees and I made an ardent request to Muruganar to teach us the complete works of Bhagavan. We impressed on him that this would be the only solace for us grieved as we were by the physical separation of Bhagavan. He remained silent for some time with tears flowing freely from his eyes.

Finally he said, ‘Let me see’.

But we would not let him go. The same day in the afternoon several of us gathered before him, each with a copy of the Collected Works. Finding that he could not refuse our insistent request, the swami began to teach us.

Once he started he would have no regard for the time taken nor did he have any concern for the trouble he had to take. As a consequence he would sometimes suffer from a splitting headache.

I would ask, ‘Swami, why did you not stop earlier? You are suffering so much.’

Childlike he would reply, ‘I do not know how to stop when talking about Bhagavan’s teachings’.

It was such a joy to be his student. He would explain everything so clearly, bringing out the majesty and beauty of Bhagavan’s teachings. He would begin with a soft voice but as the class proceeded, the volume of his voice would keep going up. At the end of the class he would often feel exhausted because of this.

One day, out of consideration for his health, I hesitantly asked him, ‘Why not teach in a soft tone throughout? Cannot the loudness be avoided?’

I was afraid that he would be annoyed.

However, he laughed profusely and said, ‘Listen, when I was a teacher, my tone used to be very loud. The teacher from the next class would come and request me to tone down my voice as he was unable to proceed with his own class. I would of course oblige and try my best to talk softly. But it would be of no avail. Soon I would find my colleague peeping into my room again. Immediately I would lower my voice.’

The innocent tone which he narrated this was very touching.