After his retirement in 1966, Papaji travelled extensively all over India, rarely staying in one place for more than a few weeks. However, once he had arranged and attended the marriages of his children in January, 1967, he felt an urge to spend more and more time in Rishikesh and Hardwar, the pilgrimage towns in northern Uttar Pradesh that are located at the place where the River Ganga leaves the foothills of the Himalayas and enters the plains. The towns are close to each other, with Rishikesh being twenty-four kilometres further upstream than Hardwar.

For most of my life I have been travelling to Rishikesh and Hardwar and spending time there. When I was a child my parents took all the family to Hardwar for the summer holidays. For most of my life I adjusted my schedule so that I could spend one or two months there every year. When I had no other commitments, I would spend much more time there. Sometimes I stayed on for years.

These are holy places. People have been meditating in Rishikesh and Hardwar, by the banks of the Ganga, for thousands of years, and many have won enlightenment there. These are the places I always like to return to when I have had long or extensive trips to meet devotees.

After performing the marriages of my son and daughter at Agra and Delhi, I decided to leave my family and relatives once and for all. It was clear that my duties had been fulfilled. I felt no desire to continue the role of a householder.

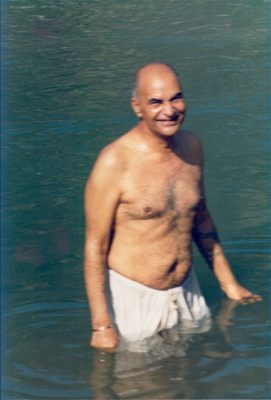

I decided to go to Rishikesh and live the life of a sadhu. I wanted to live by the Ganga, and I wanted to be alone. I moved into a cave that was located near the main ashrams of Rishikesh. As it was very close to the waterline, on several occasions the water level rose, flooding my cave. I didn’t care. When it was too wet to stay in the cave, I moved out to a nearby banyan tree that had a good, strong platform around it. The tree and the cave were not far away from the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the man who started the T.M. [Transcendental Meditation] movement. In those days, this ashram was his headquarters.

Papaji tried out several other caves in the neighbourhood. In one of them, located near a waterfall about fifteen minutes’ walk from the Ganga, he not only had to contend with the weather and the primitive living conditions, he also had to deal with the local animals who shared his water source.

For some time I tried out a nice cave that was located in the forest. About halfway to Phool Chatti on the old Badrinath pilgrimage road there is a stream that flows into the Ganga. About one kilometre upstream, away from the Ganga, there was a nice waterfall that had a cave adjacent to it. I lived there for some time.

In those days there were still many tigers around. The nearby stream was the only safe source of water for all the animals in the forest, so they all used to come there. There were also bears and elephants in the neighbourhood, and they too occasionally came to have a good drink. I could watch them from my cave without disturbing them. We lived together very peacefully. The elephants used to come and bathe under the waterfall because they liked the pressure of the falling water on their backs. They would suck up vast amounts of water with their trunks and then squirt it against their bodies. Sometimes they would shake their trunks as they were blowing out the water. When this happened, I would also get a shower while I was sitting in my cave.

I only had one close encounter with a tiger. I was down by the pool when a tiger came to have a drink. He looked at me with evident curiosity before beginning his drink. I got the feeling that he had just had a good meal, so he was more interested in drinking than in eating me.

It was around this time that Papaji had an interesting experience in which all his past lives appeared before him. This is the account he gave of it in the Papaji Interviews book:

I was quietly sitting by the banks of the Ganga in Rishikesh between Ram Jhula and Lakshman Jhula, watching the fishes moving through the water. As I sat there I had an extraordinary vision of myself, the self that had been ‘Poonja’, in all its various incarnations through time. I watched the jiva [reincarnating soul] move from body to body, from form to form. It went through plants, through animals, through birds, through human bodies, each in a different place in a different time. The sequence was extraordinarily long. Thousands and thousands of incarnations, spanning millions of years, appeared before me. My own body finally appeared as the last one of the sequence, followed shortly afterwards by the radiant form of the Maharshi. The vision then ended. The appearance of the Maharshi had ended that seemingly endless sequence of births and rebirths. After his intervention in my life, the jiva that finally took the form of Poonja could incarnate no more. The Maharshi destroyed it by a single look.

As I watched the endless incarnations roll by, I also experienced time progressing at its normal speed. That is to say, it really felt as if millions of years were elapsing. Yet when my usual consciousness returned, I realised that the whole vision had occupied but an instant of time. One may dream a whole lifetime but when one wakes up one knows that the time that elapsed in the dream was not real, that the person in the dream was not real, and that the world which that person inhabited was not real. All this is recognised instantly at the moment of waking. Similarly, when one wakes up to the Self, one knows instantly that time, the world, and the life one appeared to live in it are all unreal. That vision by the Ganga brought home this truth to me very vividly. I knew that all my lifetimes in samsara were unreal, and that the Maharshi had woken me up from this wholly imaginary nightmare by showing me the Self that I really am. Now, freed from that ridiculous samsara, and speaking from the standpoint of the Self, the only reality, I can say, ‘Nothing has ever come into existence; nothing has ever happened; the unchanging, formless Self alone exists’.

That is my experience, and that is the experience of everyone who has realised the Self.

A few years later, when I was staying in Paris, someone showed me a copy of the Nirvana Sutra. I read it and found that the Buddha had had a similar experience.