This article is about devotees and seekers who, at various times during the 20th century, ended up doing sadhana on the lower slopes of Arunachala. I hit upon this theme when I was sent a link to this Youtube clip about Swami Abhishiktananda and his time in Tiruvannamalai:

Before I discuss the content and subject of the clip, here is a list that gives some of the places with a Bhagavan connection that appear in the film:

0.58 Bhagavan’s samadhi at Ramanasramam. The black statue at the back appeared there around 1980, so I am guessing that this was filmed in the early 80s.

2.21 Adi-annamalai temple courtyard.

3.54 A sadhu sitting on the lower slopes of Arunachala, looking out towards Pavalakundru, the temple where Bhagavan lived in 1898. This is the place where his mother finally found him.

5.45 Guhai Namasivaya temple. Bhagavan lived there in 1902. It was here that Sivaprakasam Pillai met him and recorded the teachings that are contained in ‘Who am I?’

5.53 The mantapam next to Guhai Namasivaya’s samadhi. Bhagavan lived in this mantapam, as did Keerai Patti, the devotee who (according to many ashram accounts) was reborn as Lakshmi the cow.

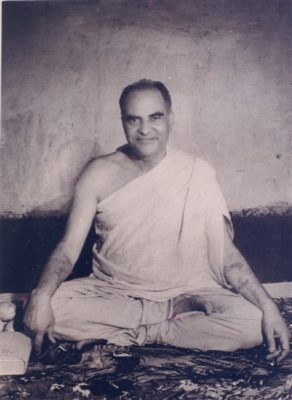

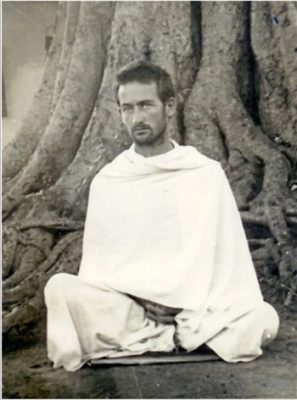

7.12 Mani Swami meditating. Mani Swami was the caretaker of Virupaksha Cave for about twenty years until the late 1980s.

9.12 Inside Virupaksha Cave, with Mani Swami singing. The lingam to his left contains the remains of Virupaksha Devar, the Virasaiva saint who occupied the cave in the 1500s, and after whom the cave is named. At his death, Virupaksha Devar turned himself into vibhuti, and this vibhuti is still reputed to be under the lingam. Bhagavan repaired the plinth under the lingam during his stay in the cave since some of the vibhuti was apparently starting to leak out.

10.25 Pachaiamman Koil, temple on the outskirts of Tiruvannamalai where Bhagavan occasionally stayed in the first decade of the 20th century. Ramanasramam parties would also camp there for the night in the early 1920s when Bhagavan and his devotees would do slow pradakshinas of the mountain that would sometimes take three days to complete.

10.43 The girivalam road, probably around 1980. In those days it was still a deserted dirt road.

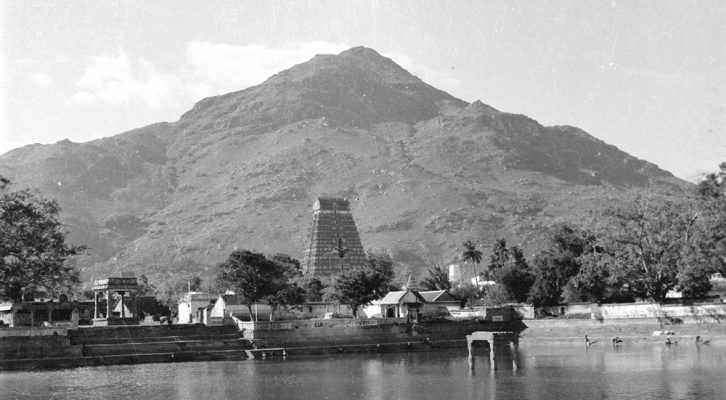

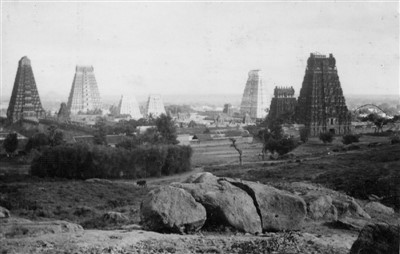

The events narrated in this film took place between 1949 and 1953, but most of the film footage seems to date from the late 70s or early 80s. In those days the hill was still mostly bare rock, and the pradakshina road was a deserted area with no electricity. The temples that lined the route were mostly quiet, sombre and empty. Today they tend to be neon-lit, painted garishly, and are often filled with sadhus who vie for the attention of passing pilgrims.

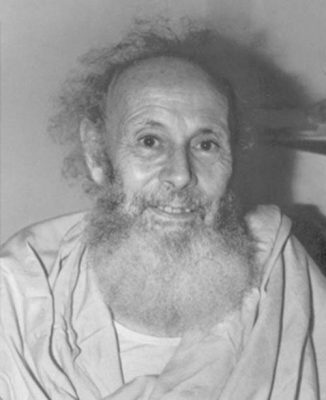

The Youtube clip mostly concerns itself with the French Catholic monk Swami Abhishiktananda, and the time he spent at Arunachala. He had darshan of Bhagavan in 1949, and in the early 1950s he came back to Arunachala to spend time meditating in its caves. An account of his meeting with Bhagavan (who made a huge and very positive impression on him) and the months he spent meditating in the caves of Arunachala can be found in his book The Secret of Arunachala which was published in the late 1970s, a few years after its author had passed away.

Before coming to India Swami Abhishiktananda had spent more than twenty years as a Benedictine monk in a French monastery, where he was known as Father Henri le Saux. After some time in India he adopted the robes and lifestyle of a Hindu sannyasi and called himself ‘Swami Abhishiktananda’. Despite the change of outfit and name, for many years he clung tenaciously to the basic tenets of the Catholic faith that he had been brought up in, feeling that the highest Christian experience and teachings were superior to their Hindu counterparts. For those who might be interested, I outlined the evolution of his theological convictions in an article that first appeared in The Mountain Path, and which now appears on my site:

At 6.43 in the Youtube clip he speaks about an important meeting he had with a man he calls ‘Harilal’. This was the name that Papaji was using at this stage of his life. His full name was Hariwansh Lal Poonja, which he abbreviated in later years to H. W. L. Poonja.

Abhishiktananda narrates in The Secret of Arunachala the story of how Harilal found him in his cave on the lower slopes of the hill and started to engage him in conversation. Abhishiktananda took it be a chance encounter, but when I spoke to Papaji about this meeting many years later in Lucknow, he told me that he had made a point of seeking him out.

I was shopping in town when I noticed this man who was also stocking up on food. It struck me that he was someone who was ready for a direct experience of the Self, so I made some enquiries, found out where he lived, and then went to visit him.

Papaji discovered that he was a Catholic priest who was still very attached to his Christian ideas about God. He encouraged Abhishiktananda to drop his concepts and instead have a direct experience of Him. In the Youtube clip Abhishiktananda paraphrases this advice by saying that Harilal told him, (7.06) ‘Free yourself from the last bonds that are holding you back. You are ready for it.’ The bonds were his Christian concepts and practices. At this stage of his life Abhishiktananda had no interest in dropping his Christian ideas. Though he had many deep experiences while he was meditating on the mountain, the direct experience of the Self eluded him.

Abhishiktananda and Papaji continued to meet regularly over the succeeding twenty years, and each time Papaji would encourage him to abandon the ideas he had about God, but without success. One meeting in North India, on the banks of a river, encapsulates the dynamic that existed between the pair of them over the years that they visited each other.

Abhishiktananda asked him, ‘What is preventing me from experiencing the Self right now?’ to which Papaji replied, ‘Throw your bag in the river and you will get it immediately’.

In the bag were Abhishiktananda’s portable altar, his Bible and prayer book, and all the paraphernalia required to conduct a Catholic mass. Papaji was saying, in effect, ‘Voluntarily give up your attachment to these things and the Self will reveal itself to you’.

The bag stayed on the river bank.

Papaji told me, ‘They made a movie about this man’s life, and this scene was included. There were two actors playing me and Abhishiktananda, and the actor playing me told him to throw the bag in the river. He refused.’

Papaji tried and failed for many years to get him, metaphorically, to throw his bag into the river, but he eventually gave up. However, something happened that caused Abhishiktananda to spontaneously abandon the beliefs that had been veiling the experience of the Self.

In 1973 he had a heart attack on the streets of Rishikesh that left him unconscious and temporarily paralysed. When he finally recovered his faculties, he instantly became aware that the Abhishiktananda who had held tightly to Catholic doctrine throughout his life had vanished, leaving just an impersonal experience of the underlying ‘I am’. This is how he wrote about it in letters to friends:

Who can bear the glory of transfiguration, of man’s dying as transfigured; because what Christ is I AM! One can only speak of it after being awoken from the dead … .

It was a remarkable spiritual experience … While I was waiting on my sidewalk, on the frontier of the two worlds, I was magnificently calm, for I AM, no matter what in the world! I have found the GRAIL! (Swami Abhishiktananda, by James Stuart, ISPCK, 1989, p. 346)

The finding of the grail was inextricably linked to losing all the previous concepts he had had about Christ and the Church. Commenting on this experience in the same book, he wrote:

So long as we have not accepted the loss of all concepts, all myths – of Christ, of the Church – nothing can be done.

From this new experiential standpoint he was able to say, from direct experience, that it was the ‘I’, rather than a collection of sectarian teachings and beliefs, that gave reality to God:

I really believe that the revelation of AHAM [‘I’] is perhaps the central point of the Upanishads. And that is what give access to everything; the ‘knowing’ which reveals all ‘knowing’. God is not known, Jesus is not known, nothing is known outside this terribly solid AHAM that I am. From that alone all true teaching gets its value. (Swami Abhishiktananda, by James Stuart, ISPCK, 1989, p. 358)

In addition to writing several books that attempted to bridge the gap between Hinduism and Christianity, Abhishiktananda had been a regular contributor to seminars and conferences on the future development of Indian Christianity. After his great experience, he received an invitation to attend a Muslim gathering in France to give a Christian point of view. In declining the invitation, he revealed how all his old ideas had been swept away, and how he no longer felt able to expound a specifically Christian viewpoint:

The more I go [on], the less able I would be to present Christ in a way which would still be considered as Christian … For Christ is first an idea which comes to me from outside. Even more after my ‘beyond life/death experience’ of 14.7 [.73] I can only aim at awakening people to what ‘they are’. Anything about God or the Word in any religion, which is not based on the deep ‘I’ experience, is bound to be simple ‘notion’, not existential.

I am interested in no Christology at all. I have so little interest in a Word of God which will awaken man within history … The Word of God comes from/to my own ‘present’; it is that very awakening which is my self-awareness. What I discover above all in Christ is his ‘I AM’ … it is that I AM experience which really matters. Christ Is the very mystery ‘That I AM’, and in the experience and existential knowledge all Christology has disintegrated. (Swami Abhishiktananda, by James Stuart, ISPCK, 1989, pp. 348-9)

Then, confirming that a lifetime’s convictions had been dropped, he went on to explain that the final Christian experience of ‘I am’ could not differ from its Hindu equivalent:

What would be the meaning of a ‘Christianity-coloured’ awakening? In the process of awakening all this colouration cannot but disappear … The colouration might vary according to the audience, but the essential goes beyond. The discovery of Christ’s I AM is the ruin of any Christian theology, for all notions are burned within the fire of experience … I feel too much, more and more, the blazing fire of this I AM in which all notions about Christ’s personality, ontology, history, etc. have disappeared. (Swami Abhishiktananda, by James Stuart, ISPCK, 1989, p. 349)

After a lifetime of meditation and research he had finally conceded that no explanation or experience could impinge on the fundamental reality, ‘I am’. Years before he had predicted that this standpoint would be the inevitable consequence of a full experience of ‘I am’:

Doctrines, laws and rituals are only of value as signposts, which point the way to what is beyond them. One day in the depths of his spirit man cannot fail to hear the sound of the I am uttered by He-who-is. He will behold the shining of the Light whose only source is itself, is himself, is the unique Self … What place is then left for ideas, obligations or acts of worship of any kind whatever?’ (Saccidananda by Abhishiktananda, ISPCK, 1974, p. 46)

When the Self shines forth, the ‘I’ that has dared to approach can no longer recognise its own self or preserve its own identity in the midst of that blinding light. It has, so to speak, vanished from its own sight. Who is left to be in the presence of Being itself. The claim of Being is absolute … All the later developments of the [Jewish] religion – doctrine, laws and worship – are simply met by the advaitin with the words originally revealed to Moses on Mount Horeb, ‘I am that I am’. (Saccidananda by Abhishiktananda, ISPCK, 1974, p. 45)

It would seem that Papaji’s initial impression that Abhishiktananda was ready for an experience of the Self was fundamentally correct, but it took him decades and a traumatic life-threatening experience to separate him from the ideas that were impeding a full awareness of the Self.

Three minutes into the Youtube there is a sequence of shots, taken on the lower slopes of the hill, of a sadhu bathing and meditating. At around 3.50 he is seen outside cave door. I have not visited this area for many, many years, but it looks to me like the entrance to the cave that Abhishiktananda lived in in the early 1950s. He first lived inside a cave that was close to Pai Gopuram Street, the street between the back of the Arunachaleswara Temple and the mountain, but that area was consumed by the expanding suburbs of the town before I arrived in Tiruvannamalai. I believe his original cave was somewhere behind the Sakti cinema. I know about the second cave that features on the film because it was next door to the house of an Australian friend of mine, Narikutti Swami.

Narikutti Swami’s original name was Barry Long. He was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1930 and lived a fairly normal life there until, around 1957, he went to the cinema to see The Razor’s Edge, a film about a western seeker who goes to India and meets an Indian guru who transforms his outlook on life. Somerset Maugham, the author of the novel that was later turned into this film, visited Ramanasramam in the late 1930s. The guru in his novel is clearly identifiable as Ramana Maharshi, although in the book he is called ‘Sri Ganesha’, and his ashram is located near Trivandrum. If anyone wants more information on how this fictional portrayal of Bhagavan came to be created, I have written about it here:

Narikutti Swami told me that he left the cinema with tears streaming down his face and a determination to go to India. He left his job in an architect’s office and travelled to Sri Lanka in April 1957 where he soon made contact with Yogaswami, a well-respected spiritual teacher in Jaffna who had briefly spent time in India with Ramana Maharshi. Narikutti Swami took him as his guru and decided to stay with him in Sri Lanka, rather than travel on to India, which had been his original intention. However, Yogaswami somehow intuited that it was Narikutti Swami’s destiny to live on Arunachala and told him to move there. Narikutti Swami must have been reluctant to do this because he waited until several years after Yogaswami passed away before he moved to Tiruvannamalai in 1970. He took up residence in a place called ‘Lakshmi Amma Cave’ and stayed there until ill-health forced him off the mountain in the early 1990s.

Since Swami Abhishiktananda’s cave was next door to where he lived, he was occasionally visited by students and fans of Abhishiktananda who wanted to see the Arunachala cave he had written about in The Secret of Arunachala. Swami Abhishiktananda became something of a cult figure in Europe in his later years, becoming famous as the man who had gone to India as a French Catholic priest before embracing and directly experiencing the traditions of Hindu religious life.

Narikutti Swami was the first person to begin reforestation on the slopes of Arunachala. By the 1960s (as you can see from the portions of the Youtube film that show the mountain) Arunachala had been almost completely denuded of all its original forests. Narikutti Swami began planting and nurturing trees in the area between Mango Tree Cave (where Bhagavan occasionally lived in the summer months) and Guhai Namasivaya Temple. Many of the trees he planted are still there and nowadays the eastern slope of the hill has better forest coverage than at any time in the last 100 years.

Incidentally, for those who are curious about his adopted name, it means ‘Little Jackal Swami’, a nickname he acquired soon after his arrival in Tiruvannamalai. A small feral dog attached itself to him in his early days on the mountain, and Narikutti did little to discourage it. Because of his association with this animal, he ended up being called the equivalent of ‘Little Dog Swami’.

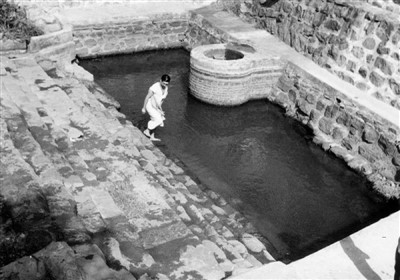

In the decades that he lived on the hill Narikutti Swami helped the local sadhus who lived alongside him with building projects and repairs. His architectural background and knowledge came in handy when the back retaining wall of Mulaipal Tirtham collapsed into the tank. Mulaipal Tirtham was and still is the main source of water for sadhus on the hill. In Bhagavan’s time at Virupaksha Cave it was the primary source of water for the devotees who congregated there.

Narikutti Swami went on a fund-raising drive and single-handedly raised the money required to repair and remodel the tirtham. He then personally supervised the building work to make sure that the water from the bathing and clothes-washing areas would never contaminate the drinking water section.

In the 1970s and 80s there were a few other foreigners who lived as sadhus in caves or temples on the eastern side of the hill. There was a French woman called Therese who had been the dentist of the Mother of Aurobindo Ashram before she moved to Tiruvannamalai in the 1970s. Her partner Richard was also a dentist, but before he came to India he had been a talented and professional pianist in Greece. He too had practised dentistry in Pondicherry before moving to Tiruvannamalai with Therese. Richard extensively remodelled a cave on the south-western side of the hill, while Therese built a house close to Mango Tree Cave which is still there today. During their many years in Tiruvannamalai Therese and Richard both used their medical expertise to maintain the health of the colony of sadhus who lived in a row of huts close to Mulaipal Tirtham.

At 5.45 of the Youtube clip there is some film of the Guhai Namasivaya Temple. A Canadian friend of mine, Nadhia Sutara, lived there as a sadhu for several years in the 1980s. Bhagavan himself lived there briefly around 1902, and in the succeeding years the mantapam, which is attached to the temple, was occupied by Keeraipatti, a woman who served Bhagavan when he lived at Virupaksha Cave. Keeraipatti is an affectionate nickname derived from keerai which are edible green leaves, and patti, which is an both an affectionate and a respectful form of address for elderly women.

The front of the mantapam where Keeraipatti stayed appears at 5.53 in the film. On the left side of the entrance is a pillar that is stained black on one side. The black stain comes from oil that Keerapatti used to do puja to an image of Ganesha that appears as a bas-relief on this pillar.