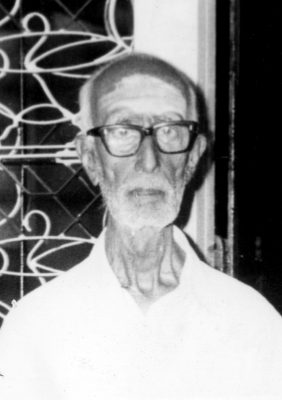

A few months ago (written in 2018) I was going through the text of The Power of the Presence, getting it ready and improved for a new edition that I hope will come out later this year. At one point I found myself adding photos to the chapter written by N. R. Krishnamurti Aiyer, a retired physics professor from Madurai who had many extraordinary experiences in Bhagavan’s presence. It brought back many pleasant memories of the times I spent with him.

I first met him in the mid-1980s in his house in Tiruvannamalai. In Ramanasramam I had seen a small booklet that contained a few of his translated verses from The Ribhu Gita. I went there hoping to persuade him to translate a larger portion of the book since I knew that it was one of Bhagavan’s favourites. At that time there were no English translations available. Since he didn’t seem very interested in the project, I didn’t press the matter. Instead, we chatted about his time with Bhagavan. One of the pleasures of living in Tiruvannamalai in that era was unexpectedly coming across people who had had contact with Bhagavan and who had extraordinary tales to tell. Once, for example, I was in a side street of Tiruvannamalai, close to Krishnamurti Aiyer’s house, when I saw a man I had noticed in Ramanasramam a few times. We had never spoken before, but we both recognised each other. I stopped to greet him and then, since he looked old enough, I asked him if he had ever met Bhagavan in person.

Much to my amazement he replied, ‘Oh yes, I am a native of Tiruvannamalai. When I was a little boy, I used to go up to Virupaksha Cave and play marbles with Bhagavan.’

He looked about sixty, not old enough to have that kind of story in his CV. However, when I politely enquired about his age, he told me he was well over eighty, which meant he could have been about nine years old in 1912. His closely-cropped hair was all white, but he had a smooth complexion that had very few wrinkles. I had noticed at Ramanasramam that he had a permanent happy smile on his face. Perhaps that was why he looked so young.

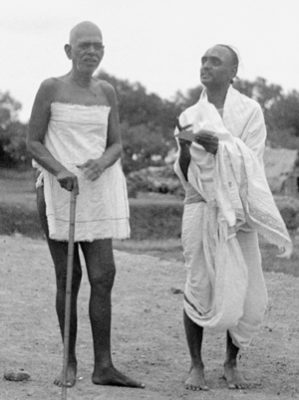

I had been introduced to Krishnamurti Aiyer by V. Ganesan, who at that time was editing The Mountain Path and managing most of the business in the Ramanasramam office. Their association went back a long way. Krishnamurti Aiyer mentioned that Chinnaswami, Bhagavan’s brother, had personally invited him to attend Ganesan’s Akshara-Abhyasam in 1941 when Ganesan was only five years old. This is the ceremony when young boys are ceremonially taught to write the Tamil alphabet for the first time. Ganesan was fortunate enough to have Bhagavan himself preside over this ceremony.

One summer, probably around 1984 or 1985, Ganesan invited Krishnamurti Aiyer to stay in a Ramanasramam room in the Morvi Compound and write down the story of his life with Bhagavan. He readily agreed. I used to visit him from time to time to listen to his anecdotes and to see how the book was progressing. One afternoon, when the book was almost completed, Krishnamurti Aiyer ended our session by saying he needed a nap. At that time he was already well into his eighties. I asked him if I could borrow the manuscript for a few hours to type out some of the stories that were in it. I had no idea what I would do with them; I just wanted to have a record that wasn’t solely dependent on my memory.

The handwritten manuscript was probably about 150 pages long at this point. Much of it contained information about his personal life and his scientific career. I wasn’t interested so much in those episodes. I just wanted to record all the details of his experiences with Bhagavan. This was the pre-computer era. I don’t think we even had copying machines in those days. I went back to my own ashram room and typed out about forty pages of material on a manual typewriter. It was a long session because I had promised to have the manuscript back in his hands in time for his next writing session.

The manuscript was eventually completed and handed over to Jayaraman, the Ramanasramam librarian, who had agreed to edit it for publication. I waited for the book to come out, but it never appeared. In the succeeding years I forgot all about it. My own abridged version lay neglected in one of my folders. About fifteen years later, when I was deciding what to include in the first volume of The Power of the Presence, I remembered these notes I had taken and decided they would make an excellent chapter. I was assuming at this point that Ramanasramam had decided, for some reason, not to publish the original book.

I went to see Sundaram, the Ramanasramam president, and asked him if he was still planning to bring out Krishnamurti’s Aiyer’s memoirs.

He frowned and replied, ‘The whole manuscript got lost. We sent it to the press but it never arrived. It turned out to be the only existing copy. The whole book has disappeared.’

I told him that I had typed out the portions of the book that dealt with Krishnamurti Aiyer’s experiences with Bhagavan and asked him if he would mind if I published them as a chapter in my own new book. He had no objection, so I went ahead. Since Krishnamurti Aiyer had passed away at this point, there was no possibility of getting a new version from him.

It seems extraordinary that the ashram would put its only copy of a valuable memoir in an envelope and post it, hoping that it would arrive at its destination, but this was not the only Bhagavan text to disappear in transit. Many years before, a portion of the Guru Vachaka Kovai manuscript was left on a bus by a devotee who was taking it to a press in Bangalore. It was later discovered to be the only copy of that portion of the text.

I had a minor role in the discovery and publication of one ashram manuscript that had been presumed lost. In the early 1980s I was going through a cupboard in the Ramanasramam office that contained all sorts of manuscripts and books. Ganesan had given me the key since I had just started work on cataloguing the ashram’s archives.

When he gave it to me, he said, ‘We are playing dog-in-the-manger with this cupboard. We bark if anyone goes near it, but we have no idea what’s in it, or if any of it is valuable. Have a look and see what you can find.’

It turned out to be a veritable treasure trove of materials on and by Bhagavan, including many manuscripts in his own handwriting that are now stored and properly preserved in the Ramanasramam archives building. Stuffed behind one of the shelves in this office cupboard was a typed manuscript that had been written by T. K. Sundaresa Iyer. It had clearly been destined for publication since there were instructions for the printer in the margins. It was a lovely little book that eventually came out under the title At the Feet of the Master. It seemed to have been written in the 1960s. I guessed it had spent about fifteen years gathering dust at the back of this cupboard.

Long after its publication I asked Ganesan why the manuscript had not been published in the 1960s.

He laughed and told me, ‘We were very poor in those days. I wanted to publish the book but the ashram’s accountant said we didn’t have any spare funds. In the end he took it off me. He must have hidden it at the back of this cupboard to stop me sending it to the press. It has been there ever since. We had no idea what had happened to it until you showed it to me.’

Nowadays, it seems hard to imagine a time when the ashram didn’t have enough money to bring out a book that is only about 100 pages long.

Krishnamurti Aiyer lived well into his nineties, retaining all his mental faculties, and seemed more than averagely healthy for his age. But he had not always been like this. In his younger days he had been chronically ill, and no amount of medical intervention had made any difference to his state. He claimed that Bhagavan had eventually cured him, but only after a long period of intense pain and suffering. I was sitting with him in his house in Tiruvannamalai when he told me the following story that dated from this era:

I had been sick for a long time. I was confined to bed and my pain and suffering were so great, I was seriously contemplating suicide, simply because I couldn’t stand the pain any more.

One day I decided that I couldn’t take any more pain. I went up to the roof of my house in Madurai with the intention of throwing myself off the parapet wall. As I stood on the roof, summoning up the courage to execute the act, Arunachala-Siva appeared before me, glowing resplendently.

‘What are you doing here?’ he asked.

I was ashamed to admit what I was doing, but I couldn’t tell a lie.

‘I have been sick for a long time. The pain is excruciating. I can’t take it any longer. I came up here to throw myself off the roof because living is too painful for me.’

Siva reprimanded me: ‘You think your problems are great, but are you the only one who experiences pain? In Tiruvannamalai people dig holes in me and light fires on me, but I don’t react. I don’t decide to commit suicide. I lie there unaffected by all these events. Now you go downstairs and behave the same way.’

Chastened by this reprimand, I went back to my bed and never contemplated suicide again.

Krishnamurti Aiyer experienced so many wonderful visionary experiences during his years with Bhagavan, when it came time for him to write his life story at Ramanasramam, this one wasn’t even included. I ended up adding it as a footnote to a passage where he was narrating at some length the story of his various ailments, and how Bhagavan eventually cured him of them.