About twelve years ago I spent a pleasant hour or so telling a curious visitor, Michelle Mikklesen, a few stories about how some of my books came to be written. She liked some of the anecdotes so much, she came back with a tape recorder and asked me to tell the stories again. Second time round, she played whatever the female equivalent of a straight man is, just prompting me with occasional questions, rather than doing a proper interview. Some days later she was nice enough to supply me with a transcript. The first part of this account is my edited version. Thank you Michelle!

I decided a few days ago (July 2014) to update the presentation by writing my own account of what book projects I have been involved in over the last twelve years. I thought it would be a couple of pages, but I ended up more than doubling the original interview.

Michelle: Can you start by telling me how you became a writer?

David: A series of events led up to it. When I was staying near Ramanasramam in 1977, I became aware that the ashram had many good spiritual books that were hard to get access to. They were locked in a room near the ashram’s cowshed, the key to which was held by a rather grumpy man in the ashram office who wouldn’t let anyone in the room. I volunteered to sort them out and turn the collection into a library that people could use.

There were thousands of books there on all kinds of spiritual topics. When I was finally given the job, I realised that most of these books had been sent to the ashram free of charge because the publishers wanted the books to be reviewed in the ashram’s magazine, The Mountain Path. I then discovered that the reviewing process was in a disorganised and moribund state. Books were being sent out to reviewers who never reviewed them, or if they did, would take so long, when the reviews finally came back, the book would be almost out of print. Realising that the flow of books would stop if I didn’t get the reviewing process properly organised, I began to do reviews myself, just to ensure that the publishers would be satisfied that their books were receiving proper attention. When the editor realised that I could write well, or at least better than most of his regular contributors, I was given other writing and editing jobs. Within a couple of years I ended up editing the whole magazine, primarily, I suspect, because no one else wanted the job. In retrospect I would say that I became a writer simply so that I could have a good supply of books to read.

Michelle: When did it occur to you to write a book, rather than just reviews or articles?

David: I think the idea came from the teachers I have been with. It didn’t seem to originate with me. When I was visiting Nisargadatta Maharaj in the late 1970s, I mentioned that I was writing reviews for The Mountain Path. He gave me a very strong look, almost a glare, and said, ‘Why don’t you write a book about the teachings? It’s the teachings that are important.’ I remember being very surprised by this suggestion. The idea had never occurred to me before. I didn’t follow it up for a long time, but when I finally got round to it, I remembered his words and the force with which he had spoken them. It seemed to be an order rather than just a suggestion.

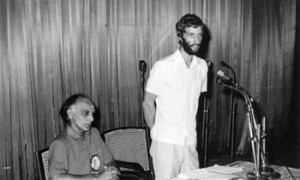

Maharaj encouraged me to write about the teachings, but at the same time he discouraged me from publicly speaking about them. Around 1980 I gave a talk in Delhi on Bhagavan’s teachings. On the way back to Tiruvannamalai I stopped in Bombay and went to see Maharaj for a few days. Someone must have told him about the talk I had given in Delhi. When he called me up to the front of the room, I went up and sat opposite him, facing him. That was where people sat when he put them on the spot.

‘No, no,’ he said, ‘sit next to me, facing the people.’

My spirits sank. I didn’t know what he had planned, but I knew I wouldn’t enjoy it.

He started off making fun of me, saying that whereas only about forty people came to hear him speak, I had just been talking to hundreds of people in Delhi. I was obviously much better than he was at this job, he said, so he invited me to give a speech to all the people there. I tried to back out, but when I realised he was serious, I gave a five-minute summary of what I had said in Delhi. I felt like an undergraduate physics student, trying to give a lecture in front of Einstein. One of his translators gave a simultaneous translation.

When it was over, he said, quietly, ‘I can’t quarrel with anything you have said. What you said was all correct.’

Then he glared at me and added, ‘But don’t waste your time giving spiritual talks until you are enlightened yourself, until you know from direct experience what you are talking about. Otherwise you will end up like that Wolter Keers.’

Wolter Keers was a Dutch advaita teacher who toured around Europe, giving lectures on advaita and yoga in at least three different languages. He was a very fluent and informative teacher and he used to come to see Maharaj regularly. Every time he came, Maharaj would shout at him, telling him he wasn’t enlightened, and that he shouldn’t set himself up as a teacher until he was. I got the message. I have never given a public talk since then.

I received more or less the same advice from Papaji. He very much encouraged me to write about him. In fact, he invited me from Tiruvannamalai to Lucknow to compile the work that was eventually published as Nothing Ever Happened. When I interviewed him for a video documentary in 1993, he said, ‘When you go back to the West, if people ask you about what happened to you in Lucknow, keep quiet. If they ask again, just laugh.’

I was asked by him to write about him, but he didn’t want me appear in front of an audience and speak about him. Other people were encouraged to speak, but were not asked to write. Different people received different orders, different advice.

Michelle: Did any other teachers encourage you to write?

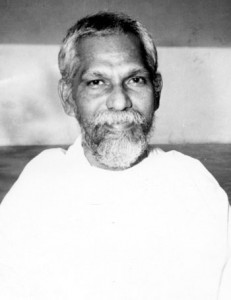

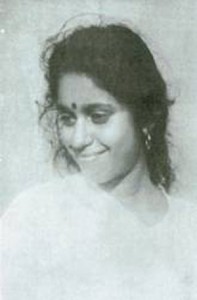

David: When I first went to Lakshmana Ashram in 1982, I was actually running away from writing. I had been working at Ramanasramam, editing their magazine and looking after their library, for several years. I just wanted to meditate and sit at the feet of a realised teacher. Within a couple of weeks of my arrival, Lakshmana Swamy asked me to write a small book about Saradamma. He explained to me that he thought she might give up her body because of her tendency to go into long, deep samadhis from which it was very difficult to bring her back to normal consciousness. He thought that if she had devotees of her own, she would have to externalise her attention more in order to deal with them. The book project was a way of letting the world know that she existed. At that time both of them were virtually unknown. I stayed in their ashram for about seven months that year. During the day there were usually two of us there, apart from Saradamma and Lakshmana Swamy. A few other people would sometimes come in the evenings. For one period of about two weeks, when Saradamma was in town with her family, I was the only person there, apart from Lakshmana Swamy.

Michelle: This was the second book you wrote, the first being Be As You Are.

David: No, it was the first. I wrote it in 1982, but it wasn’t published until around 1986.

Michelle: What happened? Why was there such a delay?

David: It’s a long story. When Lakshmana Swamy asked me to write this book, I, of course, agreed. He said that I should talk to Saradamma and get her story from her. However, when I approached her, I found that she wasn’t interested in talking. She didn’t want the book at all. She didn’t want a lot of people coming to see her, something she knew might happen if this book ever came out. She was quite content with the life she had.

I reported back to Lakshmana Swamy, telling him that Saradamma had no interest in cooperating with this project. He decided that he would have to sit next to her and compel her to tell her story. He knew that she would find it very hard to refuse his request to talk if he was there in person. This was a big bonus for me because it meant that I would get to see them both every day for about an hour while Saradamma narrated various incidents from her life.

Even with Lakshmana Swamy sitting next to her, encouraging her to speak, it was sometimes hard to get information from her. Sometimes she would talk willingly, but at other times she would close down completely and refuse to say anything. After a week or so of interviewing her, she announced that she wasn’t going to cooperate any more unless half the book was about Lakshmana Swamy. He didn’t particularly want a book about himself to be published, but he had to agree in the end because that was the only way he could get Saradamma to carry on telling her stories. The interviews resumed. Neither wanted a book about himself or herself, but both wanted a book about the other.

Lakshmana Swamy had told Saradamma about many incidents from his own life. She wrote down everything she could remember, and then interviewed him privately to get extra information. All this she wrote down in a big notebook that she eventually passed on to me. Once I had the basic story straight, I asked him many supplementary questions that he was always happy to answer.

Saradamma seemed to have almost perfect recall of just about every minute of every day of the years she was doing her sadhana. Lakshmana Swamy occasionally had to prompt her to stick to essentials. Even so, the material I was collecting was rapidly increasing every day. I realised that the ‘small booklet on Saradamma’ that Lakshmana Swamy had originally envisaged was going to be quite a substantial book.

One morning, when I went to the interview session on Lakshmana Swamy’s veranda, he announced, ‘No more research or interviews. You can go off and write the book now. I want you to finish it in two weeks.’

I was stunned. It seemed to me that there were still many more good stories to be collected, and as for writing a book from start to finish in less than two weeks, I couldn’t begin to imagine how that might be accomplished.

Two factors had combined to produce this ultimatum. Lakshmana Swamy only had a very small amount of money available for the publication of this book. He had received an estimate from a local printer that made him realise that he couldn’t afford to print a bigger book. The two-week deadline came from a plan he had to put a copy of the book on Ramana Maharshi’s samadhi on his next visit to Tiruvannamalai. He had budgeted two weeks for me to write the book and about a month to print it.

I sat down to write the book. I wrote out the first few drafts by hand and then later typed the final version on an old typewriter that had a couple of letters missing. I had to fill in the gaps by hand later. I took the two-week deadline very seriously. I seem to remember working round the clock for the last few days. I definitely stayed up all night the day before I was due to deliver the manuscript, and I think I only finished it an hour or so before Swamy’s regular 9 a.m. darshan. In those days he was much more available. Visitors could sit with him and ask questions just about every day. I prostrated before him at 9 a.m. and presented my manuscript. Saradamma wasn’t there that day, but I can’t remember why. He laughed and said that he wasn’t able to read it because he had broken his glasses the day before and wouldn’t be able to get a new pair for several days. This was the first sign that the deadline wasn’t going to be met. The last-minute rush hadn’t really been necessary. Since he couldn’t read any of it himself, at his request I read out the chapter in which Saradamma had realised the Self in his presence. He seemed to enjoy it.