John David: Am I right in thinking that from then on he pretty much stayed within the confines of the temple?

David Godman: After this dramatic arrival, he stayed in various parts of the temple for several months. The day he arrived he threw away all his money into a local tank; he shaved his head, which is a sign of physical renunciation; he threw away all his clothes and he just sat quietly, often in a deep samadhi in which he was completely unaware of his body or his surroundings. It was his destiny to stay alive and become a great teacher, so people force-fed him and looked after him in other ways. Without that particular destiny to fulfill, he would have probably given up his body or died from physical neglect. For the first three or four years he was here, he was mostly unaware of anything around him. He rarely ate, and at one time his body started to rot. Portions of his legs became open, festering sores, but he didn’t even notice.

John David: This is when he was sitting down in that kind of basement?

David Godman: Yes. have you been there? It’s called Patala Lingam. He was in that place for about six weeks. At the end of that period he had to be physically carried out and cleaned up. In his early years here he said that he would open his eyes, without knowing how long he had been oblivious to the world. He would stand up and try to take a few steps. If his legs were reasonably strong, he would infer that he had been unaware of his body for a relatively short period – perhaps a day or two. If his legs buckled when he stood to walk, he would realise that he had probably been in a deep samadhi for many days, possibly weeks. Sometimes he would open his eyes and discover that he was not in the place where he had sat when he closed his eyes. He had no recollection of his body moving from one place to another within one of the temple mantapams.

John David: Did anyone recognise him as a great saint, or at least as someone special?

David Godman: There were a few. Seshadri Swami, who was also a local saint, spotted him while he was sitting in the Patala Lingam. He tried to look after him and protect him, but without much success. Bhagavan has spoken of one or two other people who intuitively knew that he was in a very elevated state, but in those days, they were very few in numbers.

John David: Were they people in the temple?

David Godman: Seshadri Swami lived all over the place. There were probably two or three other people who even then recognised him as being something special. Some people revered him simply because he was living such an ascetic life, but there were other people who seemed to know that he was in a high state. The grandfather of a man who later became the ashram’s lawyer was one who Bhagavan said had a full appreciation of who he really was.

John David: In those days you could easily take his behavior as a sign of being a bit crazy, yes? For example, there was a man in the ashram this morning wearing a loincloth, rather like Bhagavan’s loincloth, with a French accent. He could be a famous saint or he could be a loony. It wouldn’t be very easy to decide at the moment.

David Godman: People get the benefit of the doubt here, especially if they are sitting all day, absolutely still, and not eating. That’s hard to fake. You don’t sit in full lotus, absolutely motionless, for a few days just to get a free meal. But at the same time, it doesn’t prove you are enlightened. There was a man here in Bhagavan’s time who sat eighteen hours a day in full lotus with his eyes closed. His name was Govind Bhat and he lived in Palakottu, a sadhu colony adjacent to Ramanashram. He tried to attract devotees even while Bhagavan was alive, but he didn’t do very well. In the end it is the enlightenment not the physical antics that attracts the real devotees.

John David: So how did it happen that he moved from there up onto the hill?

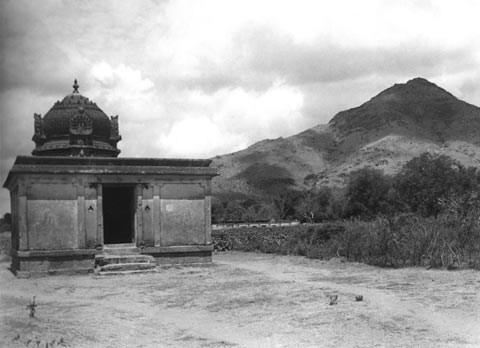

David Godman: Have you been to a place called Gurumurtham? It’s a temple about a mile out of town. A man who was looking after Bhagavan invited him to go and stay in a mango orchard that was next to this temple. He moved out there for about a year and a half. That was the furthest away from the mountain he ever went in all his fifty-four years here. Even there he was mostly unaware of his body and the world. He said his fingernails grew to be several inches long. He didn’t comb or wash his hair for a couple of years. Many years later he commented that if one doesn’t comb one’s hair it becomes very matted and it grows very quickly. By the end of his time at Gurumurtham, he had long matted hair and long fingernails. He has said that he could hear people whispering outside, saying, ‘This man’s been in there for hundreds of years’. Because of the extent of his asceticism, he looked old even when he was eighteen.

John David: From the way you’re telling the story, it has always been clear that he was a saint.

David Godman: Clear to whom? It is easy to say this in hindsight, but at the time there were many local people who had no opinion of him at all. The population of Tiruvannamalai around 1900 was probably in the region of 20,000. If twenty people came to see him regularly, and the rest didn’t bother, that means 99.9% of the local people either didn’t know anything about him, or didn’t care enough to pay him a visit. His uncle, who came in the 1890s to try and bring him home, asked people in town, ‘What’s he doing? Why is he behaving like this?’ The replies he received were not positive. His uncle was led to believe that he was just a truant who should be taken home. Even in later years there were many people in Tiruvannamalai who didn’t have a high opinion of him. The people who became his devotees are the ones who left some records, so the published opinions of him are a bit one-sided.

John David: So, when he was already twenty or so, were there devotees already coming to spend time with him?

David Godman: He arrived when he was sixteen and for the next two or three years he sometimes had one full-time attendant, plus a few people who occasionally came to see him. It wasn’t really until the early years of the last century that people started coming regularly. By the beginning of the first decade of the twentieth century he had a small group of followers. A few people brought him food regularly and a few others were frequent visitors. A large number of curiosity seekers would come to have a look at him and go away. Apart from these tourists, he seems to have had perhaps four or five regular devotees.

John David: Were those people local people?

David Godman: They were mostly locals. One woman called Akhilandamma, who lived about forty miles away, used to come from her village and bring him food once in a while. Another, Sivaprakasam Pillai, lived in another town, but he came for darshan regularly. Just about everyone else lived here in Tiruvannamalai.

John David: And he went from the mango orchard up onto the hill?

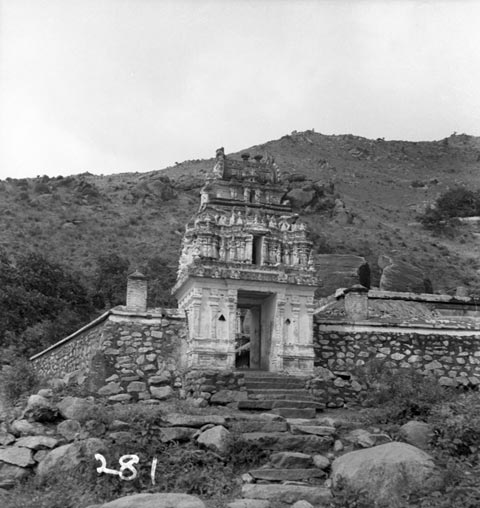

David Godman: Around 1901 he moved up to Virupaksha Cave and stayed there for about fifteen years, but it was not a good place to live all year round. In summer it was too hot.

David Godman: Things move on.

John David: But in fact there’s a stream that runs right past the cave. Whenever I’ve been there…

David Godman: It doesn’t run all year, and when Bhagavan moved into the cave it wasn’t there at all. There was a big thunderstorm one summer that produced an avalanche that carried away many of the rocks that were near the cave. After the debris had been cleared away, it was discovered that a new spring was coming out of nearby rocks. The devotees said that it was a gift from Arunachala, and Bhagavan seemed to agree with them.

John David: It seems a nice little water supply.

David Godman: It’s very seasonal. We have just had a week and a half of good rain. If it doesn’t rain, within a week it will dry up, so it’s not that good a source.

John David: Is that the same spring that goes through Skandashram?

David Godman: No, Virupaksha Cave has an independent spring. Skandashram probably has the best spring on that side of the hill. That spring also didn’t exist when Bhagavan first moved onto the hill. He went on a walk there – it’s a few hundred feet higher up the mountain from Virupaksha Cave – noticed a damp patch and recommended that it be dug out to see if there was a good water source there. There was, and the stream that now flows through Skandashram is the highest source of permanent water on the hill. It’s about 600 feet above the town.

John David: Does that mean Skandashram didn’t exist in those days?

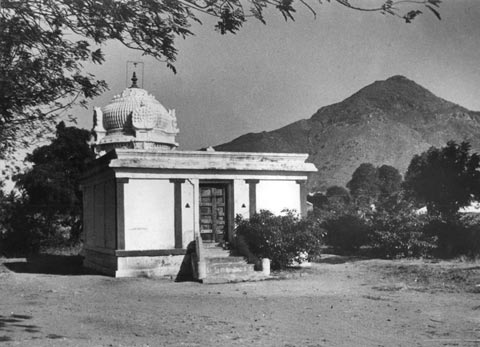

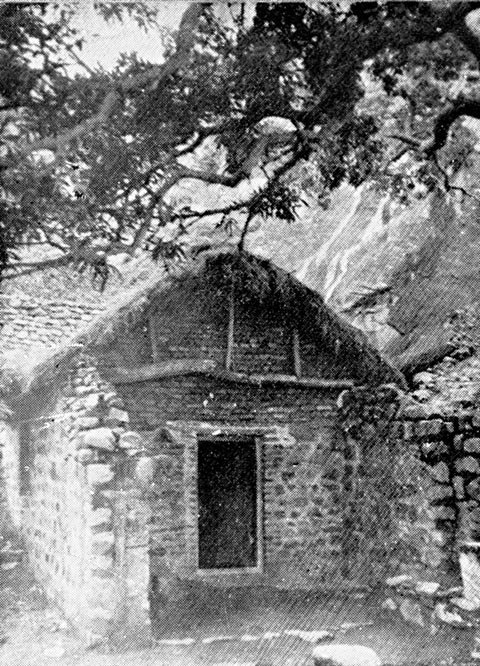

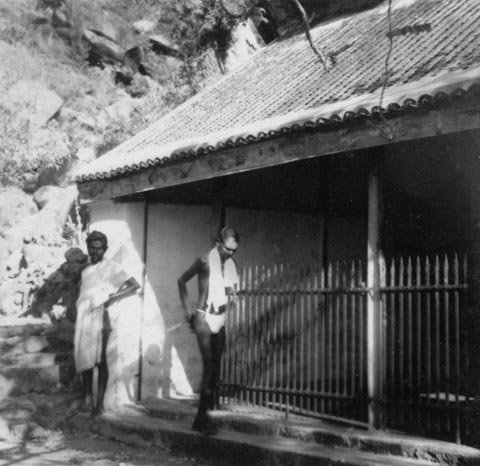

David Godman: No. It’s named after a man called Kandaswami who started building it in the early years of the last century. Kandaswami did a massive amount of work on the site. When he started it was a 45-degree scree slope. He dug back into the side of the hill and used the excavated soil and rocks to make a flat terrace on the side of the hill. He planted many coconut and mango trees, which are still there. It’s a beautiful place now, a shady oasis on the side of the hill.

John David: So when Bhagavan moved up there, it was pretty well set. There were some buildings and a terrace?

David Godman: The terrace was there and the young trees had been planted, but there was only one small hut that was not big enough for everyone. The devotees of the time did some fundraising and erected the structure that can be seen there today.

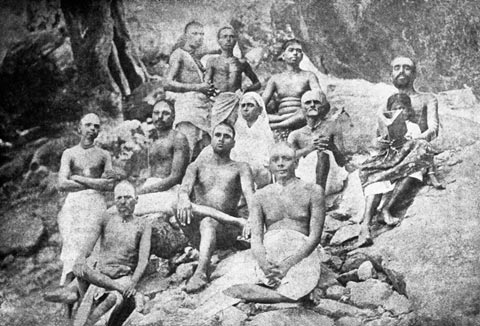

John David: Do you know how many people were there with Bhagavan? Half a dozen?

David Godman: In Virupaksha Cave about four or five would be a good average. By the time Bhagavan moved to Skandashram, the average numbers were probably up to ten or twelve. I am talking about people who lived with Bhagavan full time, and who slept with him at night. There were many other people who just visited and left.

John David: So even in the cave there were in fact people living there with him?

David Godman: Yes, they ate with him and slept there at night. Many of them left during the day to do things elsewhere. They were not sitting there all the time. They were all men, by the way. Until Bhagavan’s mother arrived in 1914, only men were allowed to sleep in Virupaksha Cave. Even though there was no formal structure, the people who lived with Bhagavan tended to regard themselves as celibate sadhus. They regarded the cave as a men-only ashram. Initially these sadhus didn’t want Bhagavan’s mother to move in with them. However, when Bhagavan declared, ‘If you make her leave, I will also leave along with her,’ they had to back down and allow her to stay.

John David: So, when he lived in the cave he wasn’t in ‘retreat’ or in ‘solitary silence’. You know, the image of Bhagavan is always of this totally silent, totally alone person.

David Godman: He behaved differently in different phases of his life. In the late 1890s, when he was in his late teens, he almost never interacted with anyone. Most of the time he just sat with his eyes closed, either in the temple or in nearby temples and shrines. He knew what was going on because in later years he would often talk about incidents from this era, but he hardly ever spoke. The period of

rarely speaking lasted for about ten years, up to about 1906. He hadn’t taken a vow of silence, he had just temporarily lost the ability to articulate sounds. When he tried to speak, a kind of guttural noise would initially come out of his throat. Sometimes he would have to make three or four attempts to get the words out. Because it was so hard to speak, he preferred silence. Around 1906-7, when he recovered his ability to speak normally, he began to interact verbally with the people around him. By this time he was also spending a lot of time wandering around by himself on Arunachala. He loved being out on the mountain. It was his main passion, his only attachment.

John David: And that would be alone? He would go around alone?

David Godman: Occasionally he would take people out for brief walks but mostly he was alone.

John David: Is it on record who was his first disciple? Or perhaps we shouldn’t say who was the earliest disciple?

David Godman: There were people who looked after him in his early years here who

could be regarded as his earliest devotees. The most prominent was Palaniswami who looked after him from the 1890s until he passed away in 1915. The two of them were inseparable for almost twenty years.

John David: So this man would have lived at the cave with Bhagavan?

David Godman: Yes, he was the full-time attendant at Virupaksha Cave. He also lived with Bhagavan at Gurumurtham.

John David: And gradually other people were attracted and would become fairly permanent. Presumably, there was no formal initiation?

David Godman: I really don’t know who decided, ‘OK, you can sleep here tonight’. There was no management, no check-in department. Everyone was welcome to come and sit with Bhagavan – all day if they wanted to. And if they were still there at night, they could also sleep there. If food was available, everyone who was present would share. Bhagavan never had much to do with who was there and who wasn’t, who was allowed to stay and who wasn’t. If people wanted to stay they stayed, and if they wanted to leave they left.

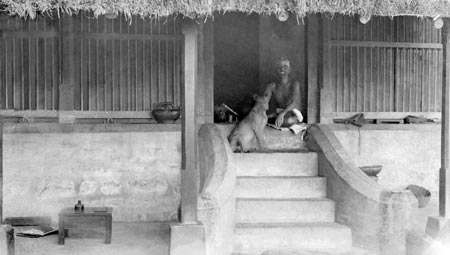

John David: And presumably that continued. I mean, he was never actively involved in managing the ashram, was he?

David Godman: In the Virupaksha period there wasn’t a lot of work going on. It was a community of begging sadhus who just stayed with Bhagavan whenever they felt like it. People would go to town, beg on the streets, collect the food, and bring it back to Virupaksha Cave. Bhagavan would mix it all up together, distribute it, and that was the food for the day. If not enough food was begged, people went hungry. Nobody was cooking, so there was no work to do except for occasional cleaning. After his mother came in 1914, the kitchen work started. Slowly, slowly it got to the situation where if you wanted to live full time with him, you had to work. Even today the people who eat and sleep full time in the ashram have to work there. It’s not a place for people who want to sit and meditate all day. If you want to do that, you live somewhere else.

John David: So that would have been when they moved to Skandashram?

David Godman: It got a bit more organised when Bhagavan moved to Skandashram, but it was still a community of begging sadhus right up to the early 1920s. Bhagavan himself went begging in the 1890s. I wouldn’t say he encouraged begging, but he thought it was a good tradition. Go out and beg your food, eat what people give you, sleep under a tree and wake up the next day with nothing. He heartily approved of a lifestyle like this, but it wasn’t one he could follow himself once he settled down and an ashram grew up around him.