John David: And he wore just a loincloth?

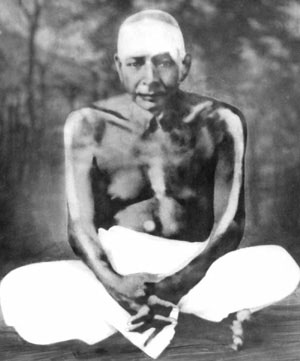

David Godman: In the beginning, for the first few months, he was naked. A couple of months after he arrived, there was a big festival in the temple. Some devotees lifted him up and dressed him in a loincloth because they knew that he might be arrested if he sat in a prominent place with no clothes on. For most of his life he only wore a loincloth, occasionally supplemented by a dhoti that he would tie under his armpits, rather than round his waist. It gets quite cold here on winter mornings, but he never seemed to want or need more clothes.

John David: When did the ashram begin to get big?

David Godman: Coming down the hill was the big move in Bhagavan’s life. When his mother died in 1922, she was buried where the ashram is now located. The spot was chosen because it was the Hindu graveyard in those days. Bhagavan continued to live at Skandashram, but about six months later he came down the hill and didn’t go back up. He never gave any reason for staying at the foot of the hill. He just said he didn’t feel any impulse to go back to Skandashram. That’s how the current Ramanashram started.

John David: So the ashram’s actually built on a Hindu burial ground?

David Godman: Yes. In those days the graveyard was well outside the town. Now the town has expanded to include Ramanashram, and the present Hindu graveyard is now a mile further out of town.

John David: How did the ashram come to take over the land round here?

David Godman: The place where Bhagavan’s mother was buried was actually owned by a math, a religious institution, in town. The man who headed that organisation had a high opinion of Bhagavan, so he handed over the land to the emerging Ramanashram. When Bhagavan’s mother died, the devotees had to get permission from the head of this math to bury her on this land, but there was no problem since he was also a devotee.

John David: And the first building, was it the shrine over the mother’s grave?

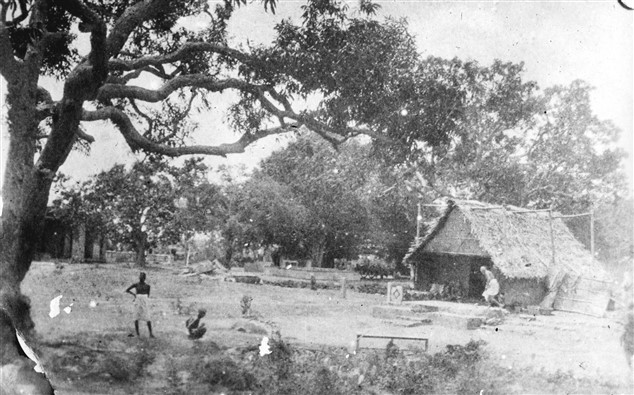

David Godman: Well, shrine is a bit of a fancy word. A really wonderful photo was taken here in 1922, shortly after Bhagavan settled here. The only building is a coconut-leaf hut. It looks as if one good gust of wind would blow it over. People who came to see him that year have reported that there wasn’t even room for two people in the room where Bhagavan lived. That was the first ashram building here: a coconut-leaf hut that probably leaked when it rained.

John David: It’s very beautiful now – water, trees, peacocks. It must have been very primitive eighty years ago.

David Godman: I talked to the man who cleared the land here. He told me there were large boulders and many cacti and thorn bushes. It wasn’t really forest. It’s not the right climate for a luxuriant forest, and there isn’t much soil. The granite bedrock is often close to the surface, and there are many rocky outcrops. This man, Ramaswami Pillai, said that he spent the first six months prising out boulders with a crowbar, cutting down cacti and leveling the ground.

John David: When the building started, was Bhagavan himself involved in that?

David Godman: I don’t think he built the first coconut leaf hut but once he moved here he was very much a hands-on manager. The first proper building over the Mother’s Samadhi was organised and built by him. Have you seen how bricks are made round here?

John David: Possibly.

David Godman: It’s like making mud pies. You start with a brick-shaped mould. You make a pile of mud and then use the mould to make thousands of mud bricks that you put out in the sun to dry. After they have been properly dried, you stack them in a structure the size of a house that has big holes in the base for logs to be put in. The outside of the stack is sealed with wet mud and fires are lit at the base. Once the fire has taken, the bottom is sealed as well. The bricks are baked in a hot, oxygen-free environment, in the same way that charcoal is made. After two or three days the fires die down, and if nothing has gone wrong, the bricks are properly baked. However, if the fires go out too soon, or if it rains heavily during the baking, the bricks don’t get cooked properly. When that happens, the whole production is often wasted because the bricks are soft and crumbly – more like biscuits rather than bricks. In the 1920s someone tried to make bricks near the ashram, but the baking was unsuccessful and all the half-baked bricks were abandoned. Bhagavan, who abhorred waste of any kind, decided to use all these commercially useless bricks to build a shrine over his mother’s grave. One night he had everyone in the ashram line up between the kiln and the ashram. Bricks were passed from hand to hand until there were enough in the ashram to make a building. The next day he did the bricklaying himself as he and his devotees raised a wall around the samadhi. Bhagavan did a lot of work on the inside of the wall because people felt that, since it was going to be a temple, the interior work should be done by brahmins. This was the only building that he constructed himself, but years later, when the large granite buildings that make up much of the present ashram were erected, he was the architect, the engineer and the building supervisor. He was there every day, giving orders and checking up on progress.

John David: You say he ‘abhorred waste’. Can you expand on that a little?

David Godman: He had the attitude that anything that came to the ashram was a gift from God, and that it should be properly utilised. He would pick up stray mustard seeds that he found on the kitchen floor with his fingernails and insist that they be stored and used; he used to cut the white margins off proof copies of ashram books, stitch them together and make little notebooks out of them; he would attempt to cook parts of vegetables, such as the spiky ends of aubergines, that are normally thrown away. He admitted that he was a bit of a fanatic on this subject. He once remarked, ‘It’s a good thing I never got married. No woman would have been able to put up with my habits.’

John David: Going back to his building activities, how involved in day-to-day decisions was he? Did he, for example, decide where the doors and windows went?

David Godman: Yes. Either he would explain what he wanted verbally, or he would make little sketches on the backs of envelopes or on scrap pieces of paper.

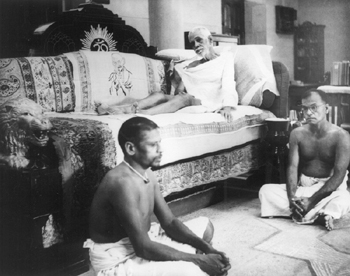

John David: What you’re describing now is a totally different Bhagavan from the one who sat in samadhi all day. Most people think that he spent his whole life sitting quietly in the hall, doing nothing.

David Godman: He didn’t like sitting in the hall all day. He often said that it was his prison. If he was off doing some work when visitors came, someone would come and tell him that he was needed in the hall. That’s where he usually met with new people. He would sigh and remark, ‘People have come. I have to go back to jail.’

John David: ‘Got to go sit on the couch.’

David Godman: Yes. ‘Got to go and sit on the couch and tell people how to get enlightened.’ Bhagavan enjoyed all kinds of physical work, but he particularly enjoyed cooking. He was the ashram’s head cook for at least fifteen years. He got up at two or three o’clock every morning, cut vegetables and supervised the cooking. When the new ashram buildings were going up in the 1920s and 30s, he was also the supervising engineer and architect.

John David: I think what you’ve just been speaking about is in a way very important in general. People have set ideas about Bhagavan. Most people have an image of him as a man who sat on a couch, looking blissful and doing nothing. What you are describing is a completely different man.

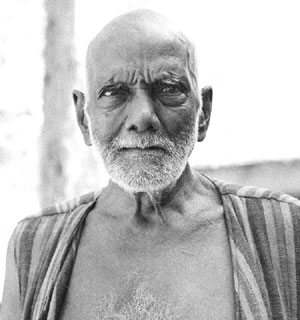

David Godman: His state didn’t change from the age of sixteen onwards, but his outer activities did. In the beginning of his life here at Arunachala he was quiet and rarely did anything. Thirty years later he had a hectic and busy schedule, but his experience of who he was never wavered during this later phase of busy-ness.

John David: I like the way you’re speaking because in a way you’re debunking a lot of spiritual myths.

David Godman: Bhagavan never felt comfortable with a situation in which he sat on a couch in the role of a ‘Guru’, with everyone on the floor around him. He liked to work and live with people, interacting with them in a normal, natural way, but as the years went by, the possibilities for this kind of life became less and less. One of the problems was that people were often completely overawed by him. Most people couldn’t act normally around him. Many of the visitors wanted to put him on a pedestal and treat him like a god, but he didn’t seem to appreciate that kind of treatment. There are some nice stories of new people behaving naturally and getting a natural response from Bhagavan. Major Chadwick wrote that Bhagavan would come to his room after lunch, go through his things like an inquisitive child, sit on the bed and chat with him. However, when Chadwick once put out a chair in the expectation of Bhagavan’s arrival, the visits stopped. Chadwick had made the transition from having a ‘friend’ who dropped by to having a Guru who needed respect and a special chair. When this formality was introduced, the visits ended.

John David: So he saw himself as a ‘friend’ not as ‘the Master’.

David Godman: Bhagavan didn’t have a perspective of his own, he simply reacted to the way people around him thought about him and treated him. He could be a friend, a father, a brother, a god, depending on the devotee’s way of approaching him. One woman was convinced that Bhagavan was her baby son. She had a little doll that looked like Bhagavan, and she would cradle it like a baby when she was in his presence. Her belief in this relationship was so strong, she actually started lactating when she held her Bhagavan doll.

Bhagavan seemed to approve of any Guru-disciple relationship that kept the devotee’s attention on the Self or the form of the Guru, but at the same time he still liked and enjoyed people who could treat him as a normal being. Bhagavan sometimes said that it didn’t matter how you regarded the Guru, so long as you could think about him all the time. As an extreme example he cited two people from ancient times who got enlightened by hating God so much, they couldn’t stop thinking about Him.

There is a Tamil phrase that translates as ‘Mother-father-Guru-God’. A lot of people felt that way about him. Bhagavan himself said he never felt that he was a Guru in a Guru-disciple relationship with anyone. His public position was that he didn’t have any disciples at all because, he said, from the perspective of the Self there was no one who was different or separate from him. Being the Self and knowing that the Self alone exists, he knew that there were no unenlightened people who needed to be enlightened. He said he only ever saw enlightened people around him. Having said that, Bhagavan clearly did function as a Guru to the thousands of people who had faith in him and who tried to carry out his teachings.

John David: During which period was Bhagavan actively involved in the building work?

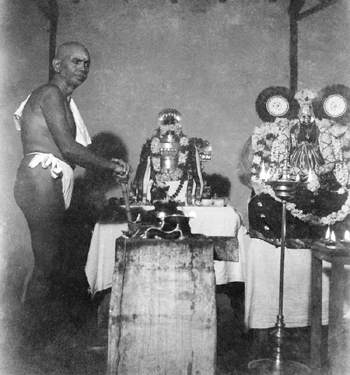

David Godman: The ashram started to change from coconut-leaf structures to stone buildings around 1930. The big building phase was 1930-42. The Mother’s Temple was built after that, but Bhagavan wasn’t supervising the design and construction of that so much. That work was subcontracted to expert temple builders. Bhagavan visited the site regularly, but he wasn’t so involved in design or engineering decisions.

John David: If anybody had visited during those twelve years they would have found a Bhagavan who was not sitting on the couch. They would have found him out working, supervising workers?

David Godman: It would have depended on when they came. Bhagavan had a routine that he kept to. He was always in the hall for the morning and evening chanting – two periods of about forty-five minutes each. He would be there in the evening, chatting to all the ashram’s workers who could not see him during the day because of their various duties in different parts of the ashram. He would be there if visitors arrived who wanted to speak to him. He walked regularly on the hill, or to Palakottu, an area adjacent to the ashram. These walks generally took place after meals. He would fit in his other jobs around these events. If nothing or no one needed his attention in the hall, he might go and see how the cooks were getting on, or he might go to the cowshed to check up on the ashram’s cows. If there was a big building project going on, he would often go out to check up on the progress of the work. Mostly though, he did his tours of the building sites after lunch, when everyone else was having a siesta.

He supervised many workers, not just the ones who put up the buildings. Devotees in the hall would bind and rebind books under his supervision, the cooks would work according to his instructions, and so on. The only area he didn’t seem inclined to get involved in was the ashram office. He let his brother have a fairly free rein there, although once in a while he would intervene if he felt that something that had been neglected ought to be done. In earlier years, up to 1926, he would also walk round the base of Arunachala quite regularly.

John David: Would a few people follow him?

David Godman: Yes, large crowds would go with him in the later years, and when he passed through town there would be even more people waiting for him, trying to feed him, or attempting to get him into their houses. He turned down all these invitations. After the 1890s he never entered a private house in town. He stopped going round the hill in 1926 because people started fighting over who should stay behind in the ashram. No one wanted to be left behind, but someone always had to remain to guard the property. Finally he said, ‘If I stop going there won’t be any more fights about who is going to stay behind’. He never did the walk again.

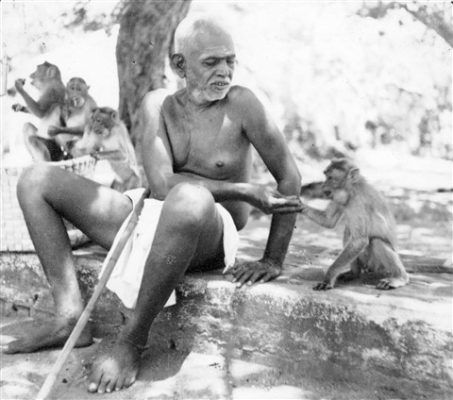

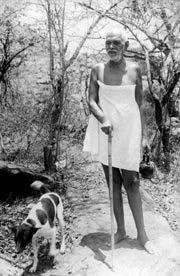

John David: You were saying he was a very natural person who liked very natural people. I presume he also liked animals.

David Godman: Almost all of them. I have read that he didn’t particularly like cats, but I don’t know what the evidence is for that. As far as I can make out, he loved all the animals in the ashram. He showed a particular fondness for the dogs, the monkeys and the squirrels.

John David: And they, presumably, lived in the ashram as well?

David Godman: Bhagavan used to say that people in the ashram were squatting on land that belonged to the animals, and that the local wild animals had prior tenancy rights. He never approved of animals being driven away either to make more room for people, or because some people didn’t like having animals around. He always took the side of the animals whenever there was any attempt t

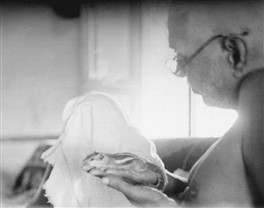

o throw them out or inconvenience them in any way. He had squirrels on his sofa. They moved in and made nests in the grass roof over his head, they ran all over his body, and had babies in his cushions. Once in a while he’d sit on one and accidentally suffocate it. They were all over the place.

John David: He sounds like a very natural person who felt it normal and natural to have animals around him.

David Godman: It was natural and normal for him, but it was not natural and normal for many the people who congregated a

round him. Bhagavan always had to fight in the animals’ corner to make sure they got proper treatment, or were not unnecessarily inconvenienced. The big new hall, the stone building in front of the Mother’s Temple, was built for Bhagavan in the 1940s. The old hall that he had lived in since the late 1920s was by then too small for the crowds of people that wanted to see him. The new hall was a large, grandiose, granite space that resembled a temple mantapam, but it was an intimidating place for some people and for all of the animals.

When Bhagavan was shown where he was going to sit, he asked, ‘What about the squirrels? Where are they going to live?’ There were no niches for them to sit in, or grassy materials to raid for their nests. Bhagavan also complained that the building would intimidate some of the poor people who

wanted to come and see him. He always saw things like this from the side of the underdog, whether animal or human.

John David: That large stone couch somehow seems to be for the wrong person.

David Godman: Yes, that wasn’t his style at all. There was a sculptor making a stone statue of him at the same time that the finishing touches were being made to this new hall. When Bhagavan was told that this new carved, granite sofa was for him, he remarked, ‘Let the stone swami sit on the stone sofa’. He eventually did move into this hall because there was nowhere else where he could meet with large numbers of people, but he didn’t stay there long.

John David: And that was about a year before he gave up his body?

David Godman: The temple over his Mother’s samadhi was inaugurated in March 1949, and Bhagavan moved into the new hall shortly afterwards. He developed a cancer, a sarcoma, on his arm that year. It physically debilitated him to the extent that he couldn’t walk to his bathroom and back. At that point his bathroom was converted into a room for him. That’s where he spent the last few months of his life.

John David: That’s the place they call the samadhi room?

David Godman: Yes. An energetic Tamil woman, Janaki Mata, came to the ashram in the 1940s. When she asked to be shown to the women’s bathroom, she was told that there wasn’t one. She arranged for one to be built, and this was the room that Bhagavan spent his final days in. It was the nearest bathroom to the new hall that he moved into in 1949. It became his bathroom at that time because no one wanted to inconvenience him by making him walk any further. He refused to let anyone help him when he walked to this bathroom, even when he was extreme

ly weak. Have you seen the video of him in his last year?

John David: Probably.

David Godman: It’s excruciating to watch. His knees have massive swellings on them, and they seem to shake from side to side. It is clear from this footage that he was extremely debilitated, but he would never let anyone help him to move around. There is an elaborate stone step in the doorway of the new hall. Devotees would have to stand by, completely helpless, as Bhagavan would attempt to climb over this obstruction. No one was allowed to offer assistance. Eventually, when this step proved to be too much of an obstacle, he moved into the bathroom and stayed there until he passed away in April 1950.

John David: Is it right that during that time he was still available?

David Godman: He was very insistent that anyone who wanted to see him could have darshan at least once a day. When people realised he wasn’t going to be here much longer, the crowds increased. For the last few weeks there was a ‘walking darshan‘. People would file past his room and pranam to him one by one.

John David: And that went on until his last day?

David Godman: Yes, he gave his final public darshan on the afternoon of the day he died.

John David: Yes, I actually met someone who walked past him the day before he died.

David Godman: He insisted that the public should have as much access as possible. Up until the 1940s, the doors of his room were open twenty-four hours a day. If you wanted to see him at 3 a.m., no one would stop you from walking in and seeing him. If you had some problem, you could go and tell him in the middle of the night.

John David: So even though he was doing a lot of work – cutting vegetables, working on the buildings and so on – he was, in fact, always available?

David Godman: In that era of his life there weren’t too many people around him. You are talking about the years when he was actively involved in cooking and building work. In those days, if a group of people came to see him, he would go to the hall to see what they wanted. Everybody who lived in the ashram had a job. You were either working in the cowshed or the kitchen, the garden, the office, and so on. These ashram residents were not allowed to sit with Bhagavan during the day because they had work to do. In the evening all the ashram workers would gather around Bhagavan, and for a few hours they would generally have him to themselves. The visitors would usually go home in the evening. The people whom he saw during the day in the hall would be visitors to the ashram, along with a few devotees who had houses nearby.

John David: Was everyone free to question him?

David Godman: In theory, yes, but many people were far too intimidated to approach him. He would sometimes talk without prompting, without being questioned. He liked to tell stories about famous saints, and he often told stories about what had happened to him in various stages of his life. He was a great storyteller, and whenever he had a good story to tell, he would act out the parts of the various protagonists. He would get so involved in the narratives, he would often start crying when he came to a particularly moving part of the story.

John David: So the impression of him being silent is not really true?

David Godman: He was silent for much of the day. He told people that he preferred to remain in silence, but he did speak, often for hours at a time, when he was in the mood. I’m not saying that everyone who came to see him got a prompt verbal answer to his or her question. You could come and ask an apparently earnest question, and Bhagavan might ignore you. He might stare out of the window and show no sign that he had even heard what you had said. Someone else might come in and ask a question and get an immediate reply. It sometimes looked like a bit of a lottery, but everyone in the end got what they needed or deserved. Bhagavan responded to what was going on in the minds of the people who were in front of him, not just to their questions, and since he was the only person who could see what was going on in that sphere, his responses at times seemed to outsiders to be occasionally random or arbitrary. Many people would ask something and not get a spoken answer, but they would find later that merely sitting in his presence had given them the peace or the answer they required. This was the kind of response that Bhagavan preferred to make: a silent, healing stream of grace that gave people peace, not just a satisfactory spoken answer.

John David: When did he begin to give out teachings, and what were they? I have been told that when he was living in a cave on the hill someone came to him and asked what his teachings were. He apparently wrote them out in a small booklet. Can you say something about this?

David Godman: This was 1901. He didn’t even have a notebook. A man called Sivaprakasam Pillai came and asked questions. His basic question was ‘Who am I? How do I find out who I really am?’ The dialogue developed from there, but no words were spoken. Bhagavan wrote his answers with his finger in the sand because this was the period in which he found it difficult to articulate sounds. This primitive writing medium produced short, pithy answers. Sivaprakasam Pillai didn’t write down these answers. After each new question was asked, Bhagavan would wipe out his previous reply and pen a new one with his finger. When he went home, Sivaprakasam Pillai wrote down what he could remember of this silent conversation. About twenty years later he published these questions and answers as an appendix to a brief biography of Bhagavan that he had written and published. I think there were thirteen questions and answers in this first published version. Bhagavan’s devotees appreciated this particular presentation. Ramanashram published it as a separate booklet, and with each edition more and more questions and answers were added. The longest version has about thirty. At some point in the 1920s Bhagavan himself rewrote this series of questions and answers as a prose essay, elaborating on some answers and deleting others. This is now published under the title Who Am I? in Bhagavan’s Collected Works, and separately as a small pamphlet. It is simply Bhagavan’s summary of answers written with his finger more than twenty years before.

John David: It sounds fairly brief.

David Godman: Yes, it is probably about eight pages in most books.

John David: The key is this question ‘Who am I?’ Is that right?

David Godman: It’s called Who am I? but it covers all kinds of things: the nature of happiness, what the world is, how it apparently comes into existence, how it disappears. There is also a detailed portion that explains how to do self-enquiry.

John David: You could say something on that. I’ve personally been reading about self-enquiry for many years but it’s never quite clear exactly what it is. Is it something you do in the morning as a practice? Is it something you do once or regularly? Is it like a breathing technique or a type of meditation?

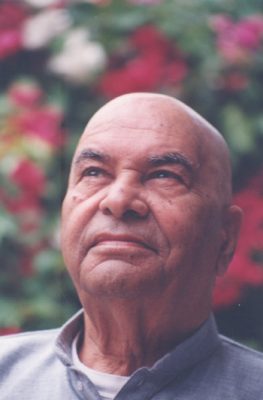

David Godman: Papaji always used to say, ‘Do it once and do it properly’. That’s the ideal way, but I only know one person who has got the right answer first time.

John David: Was that Papaji?

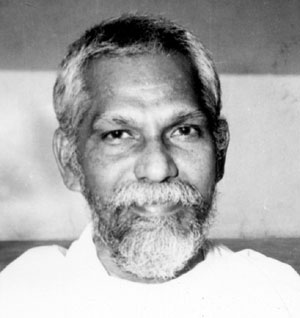

David Godman: Papaji never did self-enquiry, although he did advocate it vigorously once he started teaching. The person I am thinking of is Lakshmana Swamy. He, too, had not done any self-enquiry before. He had been a devotee for only a few months and during that time he had been repeating Bhagavan’s name as a spiritual practice. In October 1949 he sat in Bhagavan’s presence and closed his eyes. The question ‘Who am I?’ spontaneously appeared inside him, and as an answer his mind went back to its source, the Heart, and never appeared again. In his case it was a permanent experience, a true Self-realisation. In both cases there had been no prior practice of self-enquiry, and in both cases the question ‘Who am I?’ appeared spontaneously within them.

It wasn’t asked with volition.

In my opinion being in the physical presence was just as important as the asking of the question. Many other people have asked the question endlessly without getting the result that he got from having the question appear in him once. I should also like to point out that he had his Self-realisation experience in the last few months of Bhagavan’s life. Though his body was disintegrating, physically enfeebling him, his spiritual power, his physical presence, remained just as strong as ever.

John David: Are you saying that self-enquiry is not a practice, that it is not something that we should do laboriously, hour after hour, day after day?

David Godman: It is a practice for the vast majority of people, and Bhagavan did encourage people to do it as often as they could. He said that the practice should be persisted with, right up to the moment of realisation. It wasn’t his only teaching, and he didn’t tell everyone who came to him to do it. Generally, when people approached him and asked for spiritual advice, he would ask them what practice they were doing. They would tell him, and his usual response would be, ‘Very good, carry on with that’. He didn’t have a strong missionary zeal for self-enquiry, but he did say that sooner or later everyone has to come to self-enquiry because this is the only effective way of eliminating the individual ‘I’. He knew that most people who approached him preferred to repeat the name of God or worship a particular form of him. So, he let them carry on with whatever practice they felt an affinity with. However, if you came to him and asked, ‘I’m not doing any practice at the moment, but I want to get enlightened. What is the quickest and most direct way to accomplish this?’ he would almost invariably reply, ‘Do self-enquiry’.

John David: Is he on the record as saying that it is the quickest and most direct way?

David Godman: Yes. He mentioned this on many occasions, but it was not his style to force it on people. He wanted devotees to come to it when they were ready for it.

John David: So even though he accepted whatever practices people were involved in, he was quite clear the quickest and most direct tool would be self-enquiry?

David Godman: Yes, and he also said that you had to stick with it right up to the moment of realisation. For Bhagavan, it wasn’t a technique that you practiced for an hour a day, sitting cross-legged on the floor. It is something you should do every waking moment, in combination with whatever actions the body is doing. He said that beginners could start by doing it sitting, with closed eyes, but for everyone else, he expected it to be done during ordinary daily activities.