This was an article I wrote for The Mountain Path in 1990. It was published there, without the concluding poem, in 1990, pp. 26-35.

Prior to the advent of Ramana Maharishi, Tiruvannamalai’s most famous saint was probably Arunagirinatha, a Murugan bhakta who lived at the foot of Arunachala in the fourteenth century. Reliable information about him is hard to come by because the earliest account of his life was not published until the nineteenth century, about 500 years after he died. This hagiographical version, which has several variations, contains the following principal elements.

Arunagirinatha was born in Tiruvannamalai and spent the greater part of his life there. He was reputed to be the son of a courtesan called Muttammai. As he grew up, he found the company of courtesans so attractive, he spent most of his time in their houses. When his mother died, all the properties he inherited from her were squandered to pay for his lust.

Arunagirinatha had a sister, Adi, who was very fond of him. Taking advantage of her affection, Arunagirinatha persuaded her to part with her jewels and all her other possessions so that he could continue to indulge his appetite for the local courtesans. He continued with this way of life for many years. As he became older, his body became diseased and the better class of courtesan began to jeer at him and avoid his company.

The major turning point in his life occurred when he had spent all his sister’s money. Not knowing that she was destitute, he approached her again in the hope of getting another hand-out. His sister, who had nothing left except the clothes she was wearing, told him that her funds were exhausted. Since she still loved her brother, and since she still wanted to be of assistance to him she offered him her own body, saying, ‘If your lust is so insatiable, you can use my body for your sexual satisfaction’.

These words deeply affected and shamed Arunagirinatha. He mentally reviewed the wasted years of his life and came to the conclusion that he had been committing crimes against God. As his sense of shame deepened, he decided to commit suicide by jumping off one of the gopurams in the Arunachaleswara Temple. He climbed the tower, but before he was able to jump, Lord Murugan manifested before him and held him back. In some versions of the story, Arunagirinatha actually jumped and Murugan had to catch him before he died on the paving stones below.

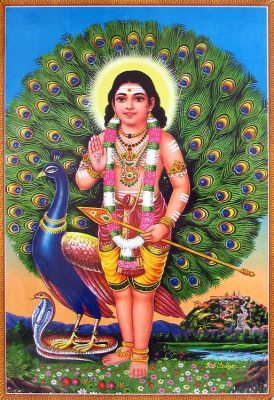

Murugan embraced him. Then, with his vel, (the spear that he always carries) he wrote a mantra on Arunagirinatha’s tongue, gave him a japa mala and commanded him to sing songs in praise of him. Arunagirinatha was initially hesitant, claiming that he had no knowledge of Tamil prosody, but when Murugan encouraged him by giving him the first line of a song, Arunagirinatha found that he could effortlessly compose and sing the remainder. Murugan disappeared, leaving Arunagirinatha a totally transformed man. His diseases vanished and he became an ecstatic bhakta whose devotion manifested as a stream of new songs, all in praise of Murugan, his deliverer. He toured the town of Tiruvannamalai, composing and singing songs as he went. Later on, he travelled throughout India, still singing his songs, and visited many of the country’s famous pilgrimage centres. Traditional accounts say that he composed more than 16,000 songs in praise of Murugan. Most of them have been lost, but more than 1,300 of the surviving ones have been collected together in a work called Tiruppugazh (The Glory of God), which has now become one of the classics of Tamil devotional literature.

So much for the traditional account. If one turns from this to the historical evidence and the biographical and cultural references in Arunagirinatha’s poetry, one is likely to conclude that this account, though it contains a large germ of truth, has been greatly embellished and sensationalised.

From one reference in the Tiruppugazh it is clear that Arunagirinatha came from a Hindu family whose ancestral deity was Murugan:

O Skanda [Murugan]! Glorious God of the hills! Pray bestow your blessings, accepting the ardent worship of this humble son to you, my ancestral deity.

All the translations of Arunagirinatha’s poems in this article have come from Saint Arunagirinatha, by Swami Anavananda, published by Pongi Publications, Madras, 1975. Two of the translated extracts are from Kandar Alankaram, while the remainder are from Tiruppugazh.

Though there is little doubt that the verses of the Tiruppugazh were brought into existence by divine inspiration, a study of their contents reveals that Arunagirinatha was a highly educated man. His songs exhibit a familiarity with the Tevarams, the Tirukkural and numerous other Tamil scriptural and philosophical works. His compositions are also sprinkled with Sanskrit words and expressions which indicate that he had studied the Itihasas, the Puranas, the Gita, the Upanishads, the Agamas and the Mantra and Tantra Sastras. Some commentators feel that the vast erudition he shows in his compositions indicates that he must have come from a family of brahmin pandits. It is not therefore likely that he was the son of a courtesan, for with such a background he would not have received a scholarly education.

It was the lot of many learned men in Arunagirinatha’s day to earn their living by composing poems in praise of rich men. Arunagirinatha himself admits that he took up this profession in order to be able to afford the fees of the local prostitutes:

To me who seek the company of prostitutes all the time, spending on them whatever little money I earn by bestowing lavish praises on men who lack wisdom, who never pray to your holy feet, who are dunces, who indulge in devilish activities and who have no sense of gratitude – pray, Murugan, grant me moksha [from all this].

One can deduce from this that he was already a reasonably competent poet before his encounter with Murugan and that Murugan merely enhanced his talent, enabling him to compose extempore verses that were both devotional and literary masterpieces.

Some references in the Tiruppugazh show that he was a married man and that his immoral behaviour outraged his family and made him the laughing stock of everyone in town:

[I was] ridiculed and jeered at by my wife, by the people of the town, by the women of the place, by my father and my relatives. I was treated as a despicable person by the very people whom I have loved. With everyone scolding me or indulging in loose talk about me, my mind became confused and full of gloom. I thought within myself, ‘Is it for this that I strove to obtain this human body which is a treasure indeed?’

This mention of his family seems to contradict the traditional story that casts him as an orphan who frittered away his inheritance on sensory indulgences.

Arunagirinatha was clearly aware that his immoral behaviour was sinful in the sight of God. In one of his verses he lamented: ‘Will I ever get to know how to attain your holy feet before becoming too old? I am wasting my youth by indulging in sinful and sexual pleasures.’

His life took a change for the better when he came into contact with an unknown mahatma who advised him to meditate on Lord Murugan. Arunagirinatha at first ignored the advice, but after some time he began to meditate in the manner prescribed by the mahatma. For several hours each day he sat in front of an image of Murugan, but his mind, weakened by years of dissipation, was unable to concentrate for any length of time. In despair Arunagirinatha decided to end his life. It was at this opportune moment that Lord Murugan appeared on a dancing peacock, halted him in the act and took possession of him. There is no support in any of Arunagirinatha’s verses for the well-known story that his suicide attempt was precipitated by his sister’s offer of her body, nor is it indicated anywhere that his chosen method of suicide was to jump off one of the gopurams. However, the attempted suicide and the divine intervention that prevented it are clearly documented:

When I was about to shed life from my body, out of compassion for me and to elevate me to a better and praiseworthy status, you came upon the scene, dancing, accompanied by your celestial devotees and showered grace on me.

In some of his other verses Arunagirinatha attempted to convey the joy that this first darshan brought to him and the transforming effect that it had on his mind:

The kadamba garland that he wore suffused me with its cloying fragrance. My breath was held. His moon-like countenance and tender smile caused such joy and ecstasy that my mind was lost. The moment he looked at me a cool liquid light poured out from his long lotus eyes. It filled my heart, tasting like nectar, and I was lost to him forever.

Overwhelmed by the experience, Arunagirinatha surrendered wholeheartedly to Lord Murugan and resolved to keep an awareness of the Lord’s name continuously in his mind:

O mind of mine, it’s good you decided to surrender. See him on his peacock vahana. He has now taken charge of you. Doubt not, there is no greater state. Dwell on his holy name always …

After his dramatic conversion Arunagirinatha made extensive tours of India, singing Murugan’s praises and repeating his name. On many occasions during his travels his devotion was rewarded when Murugan appeared to him in the form of a vision. It is worth examining some of these verses that he sang, for they give a revealing insight into his spiritual state, his beliefs and the practices he enjoined on others.

We can begin with a description of his own exalted state. In the following verse he recalls how he transcended his dualistic relationship with God and established himself in the supreme state of Self. As Ramana Maharshi would do centuries later, he utilised the term ‘mauna’ or ‘silence’ to convey the essence of this indescribable state:

It [mauna] has no length and breadth and its extent cannot be comprehended by anyone. [It is] where everything becomes clear. No longer engaged in outward puja, I experienced profound wisdom and spread flowers of joyous love. Can I [now] worship that form of Siva which is beyond the Vedas, beyond thought and speech, beyond conscious self-effort and beyond, beyond all subtle desires?

Arunagirinatha never stated explicitly how long it took him to attain this realisation; he merely said that it came about sometime after his first encounter with Lord Murugan:

The appointed day of Yama’s coming having passed by, the desire to be always sporting with women having left me, having cut asunder the troubles caused by the five senses, I began to sing the glory of your lotus feet. I meditated upon you, O Lord of Tiruchendur [Murugan], and having come to know you, wisdom dawned upon me. O Kanda, I have known you, known you well. Going on the path of inner experience, I attained the true knowledge, destroying the I-am-the-doer sense at its root. [Afterwards], the ever-functioning mind was dead. Speech ceased to be …

‘The appointed day of Yama’s [the god of death’s] coming’ might be a reference to his attempt to commit suicide. Having survived his destined date with death, he became a transformed man whose focus switched exclusively to his relationship with Murugan.

Although Arunagirinatha seems to have realised the Self fairly quickly, probably because of his latent spiritual maturity, he recognised that most devotees could only progress slowly, step by step. Like many other teachers before and after him, he told such people that they should first learn to quieten their minds:

Before I go down the steps of the bhakti ghat to bathe in the sea of ananda, the restless waves of the mind, free of all silt, must first subside.

To effect this subsidence Arunagirinatha recommended that devotees should live a life of purity and follow traditional practices:

By engaging in charity, by observance of festivals, by external worship of God; by the study of scriptures, by the control of the senses, by purity of thought and action, by observance of dharma, by adopting an attitude of compassion, and lastly, by rendering personal service to the Guru, one soon attains purity of mind.

When these practices mature, the grace of the Lord manifests in full measure and takes one to the goal:

Control your mind, give up anger, always perform charity, remain in the sattvic state of repose, free from rajas and tamas. Jnana Vel [the spear of jnana wielded by Murugan] of its own accord, without seeking or effort, will [then] bestow its grace on you.

Having been transformed by the grace of the Lord from a life of debauchery to a state of Self-knowledge, Arunagirinatha could speak with authority on the redeeming power of grace, the necessity of surrender, and the effectiveness of meditating on the name and form of the Lord. As a result of his own experiences Arunagirinatha clearly felt that the path of devotion and surrender was the easiest and most direct route to God. He therefore discouraged his listeners from engaging in other practices, deeming them to be either counter-productive or futile. For example, in several of his verses, written from the standpoint of a devotee, he makes very blunt and outspoken remarks about the uselessness of traditional yoga practices. In other places he is equally negative about pandits and philosophers who get bogged down in intellectual disputes about religion.

The practice of yoga to make the body steady by controlling the breath, … the awakening of the fire [kundalini] in the solar plexus and the resulting preoccupation with such practices that cause mental anxiety should be given up. I should strive to control the five senses of the body by rooting out their mischief completely. I should give up the sense of doership. I desire to attain the mauna state where there is no feeling of insufficiency, the brahmic state of non-differentiation and the house of moksha by surrendering at the lotus feet of God Kumara [Murugan].

I have had enough of the company of those persons belonging to one or the other of the six religious faiths, shouting, doubting, disputing, asserting and debating with each other about the superiority of the tenets of their respective faiths. Also [I have had enough] of those who have only taught themselves for the purpose of engaging in such controversies or for the sole purpose of performing ritualistic worship. Enough also of those who spend their times in mantras and calculations concerning yantras and chakras, their layouts with angles and junctions as found in Siva Tantras and Agamas. O Lord Murugan! Grant me moksha without my having to meander by fruitless and circuitous routes.

O yogis, by concentrating your two eyes on the tip of your nose and by controlling your breath from the muladhara to the head so that not even a single breath goes out of your body, you are trying to get moksha. You have forgotten to follow the easier and simpler way. If you concentrate your mind on Vallinayaka’s [Murugan’s] feet, it is easy to get moksha.

I do not want to be a foolish yogi by practising the control of respiration and consuming large quantities of herbs and roots, hoping to preserve and protect this mortal body as long as one wishes. Bless me, O Muruga, to avoid the ordeals of such disciplines that produce a certain rigidity by mala maya [the contaminating power of maya] and instead lead me to a daily life disciplined by jnana and possessed of religious piety. Bless me further, O Lord, to become a great yogi established in the reality of Siva, a state without differentiation of the Self from the objects around.