When Thayumanavar approached him and asked if he could become his disciple, Mauna Guru nodded his head, thereby giving his consent. Thayumanavar then asked if he could follow him wherever he went. Mauna Guru responded by telling him ‘Summa iru,’ which can mean ‘Be still,’ ‘Be quiet,’ and also ‘Remain as you are’. This one phrase apparently brought about a major spiritual transformation in Thayumanavar. In later years, when he began to write ecstatic devotional poetry, he frequently mentioned this event, this phrase, and the effect it had on him. He frequently called it ‘the unique word’ in his verses (including the one cited in the last quotation). ‘Summa iru‘ becomes one word in written Tamil by the addition of a ‘v’ as a euphonic connection: ‘summaviru‘. The same process operates in Tiruvannamalai where the ‘v’ connects a word that ends with the letter ‘u’ and a word that begins with an ‘a’.

This phrase was also used by Bhagavan, often with similarly dramatic effect. Muruganar has written in several of his poems that Bhagavan enlightened him by uttering this phrase:

Saying, ‘Enough of dancing, now be still [summa iru],’ Padam [Bhagavan] bestowed on me the state of true jnana that exists forever in my Heart as my own nature.

The sovereign grace of Padam completed my sadhana with the words ‘Be still’. What a wonder is this! (Padamalai, ‘Padam’s Grace Towards Muruganar’, vv. 168, 170, p. 354)

In a recent issue of The Mountain Path ( ‘Aradhana’ issue, 2004, pp. 75-83) there was a report of how a shorter version of this phrase, ‘iru‘, meaning ‘be’ or ‘stay’, effected a life-transforming change in Tinnai Swami.

The ‘unique word’, summa iru, uttered by a qualified Guru, has an immediate and liberating impact on those who are in a highly mature state. For the vast majority, though, hearing this word from the Guru’s lips is not enough. Bhagavan discussed this in the following dialogue, which he illustrated with more verses from Thayumanavar.

A young man from Colombo asked Bhagavan, ‘J. Krishnamurti teaches the method of effortless and choiceless awareness as distinct from that of deliberate concentration. Would Bhagavan be pleased to explain how best to practise meditation and what form the object of meditation should take?’

Bhagavan: Effortless and choiceless awareness is our real nature. If we can attain it or be in that state, it is all right. But one cannot reach it without effort, the effort of deliberate meditation. All the age-long vasanas carry the mind outward and turn it to external objects. All such thoughts have to be given up and the mind turned inward. For that, effort is necessary for most people. Of course, every book says ‘Summa iru‘, i.e., ‘Be quiet or still’. But it is not easy. That is why all this effort is necessary. Even if we find one who has at once achieved the mauna or supreme state indicated by ‘Summa iru‘, you may take it that the effort necessary has already been finished in a previous life. So, that effortless and choiceless awareness is reached only after deliberate meditation. That meditation can take any form which appeals to you best. See what helps you to keep away all other thoughts and adopt that method for your meditation.

In this connection Bhagavan quoted verses 5 and 52 from ‘Udal Poyyuravu’ and 36 from ‘Payappuli’ of Saint Thayumanavar. Their gist is as follows. ‘Bliss will follow if you are still. But however much you may tell your mind about the truth, the mind will not keep quiet. It is the mind that won’t keep quiet. It is the mind which tells the mind “Be quiet and you will attain bliss”.’ Though all the scriptures have said it, though we hear about it every day from the great ones, and even though our Guru says it, we are never quiet, but stray into the world of maya and sense objects. That is why conscious deliberate effort is required to attain that mauna state or the state of being quiet. ( Day by Day with Bhagavan, 11th January, 1946)

This is the full version of the three verses that Mudaliar summarised:

‘Remain still, mind, in the face of everything!’

This truth that was taught to you,

where did you let it go?

Like wrestlers, bent upon their bout, you raised your arguments.

Where is your judgement? Where, your wisdom?

Begone! (‘Udal Poyyuravu’, verse 5)Bliss will arise if you remain still.

Why, little sir, this involvement still with yoga, whose nature is delusion?

Will [this bliss] arise

through your own objective knowledge?

You need not reply, you who are addicted to ‘doing’!

You little baby, you! (‘Udal Poyyuravu’, verse 52)Though I have listened unceasingly to the scriptures

that one and all declare,

‘To be still is bliss, is very bliss,’

I lack, alas, true understanding,

and I failed even to heed

the teachings of my Lord, Mauna Guru.

Through this stupidity

I wandered in maya’s cruel forest.

Woe is me, for this is my fated destiny. (‘Payappuli’, verse 36)

Bhagavan also quoted ‘Udal Poyyuravu’, verse 52 in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, talk no. 646.

One may presume from the complaints in the last verse that Thayumanavar was not one of the fortunate few who attained liberation instantly merely by hearing his Guru tell him ‘Summa iru‘. As Bhagavan remarked in an earlier quotation, it is necessary for almost all people to make some conscious effort to control the mind. Thayumanavar’s Guru accepted that this was the case with Thayumanavar and he consequently gave him detailed instructions on how he should pursue his sadhana. Thayumanavar recorded many of these instructions in his verses, some of which were selected by Bhagavan and included in the Tamil parayana at Ramanashram.

During Bhagavan’s lifetime Tamil poetic works were chanted in his presence every day. Initially, at Skandashram, only Aksharamanamalai was chanted, but as the years went by, more and more works were added. By the 1940s there was a prescribed list of poems, all selected by Bhagavan himself, that took fifteen days to complete at the rate of about one hour per day.

These are some of the verses from Thayumanavar that Bhagavan selected. The first three describe the suffering inherent in samsara, while the remainder contain Arul Nandi Sivachariar’s prescriptions for transcending it:

In all people, as soon as the ego-sense known as ‘I’ arises to afflict them,

the world-illusion, manifesting as multiplicity, follows along behind.

Who might have the power to describe the vastness

of the ocean of misery that grows out of this:

as flesh; as the body; as the intellectual faculties;

as the inner and the outer; as the all-pervasive space;

as earth, water, fire, and air; as mountains and forests;as the multitudinous and mountainous visible scenes;

as that which is invisible, such as remembering and forgetting;

as the joys and sorrows that crash upon us, wave upon wave, in maya’s ocean;

as the deeds that give rise to these;

as the religions of manifold origin that [try to] put an end to them;

as their gods, as their spiritual aspirants, and as the methods

described in many a treatise that bear witness to their practices;

and as the doctrinal wrangling amongst them?

It is like trying to count the fine grains of sand on the seashore.In order to teach me to discern the truth

of how all these woes, impossible to measure –

which spontaneously accumulate, multiplying bundle by bundle –

were insubstantial, like the spectacle of a mountain of camphor

that disappears entirely at the touch of a flame,

he associated with food, sleep, joy, misery, name-and-place,

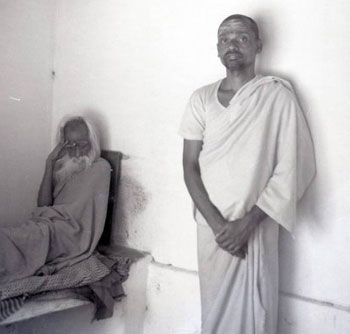

and wearing a bodily form similar to my own, he came as the grace-bestowing Mauna Guru

to free me from defilement, in just the same way that a deer

is employed to lure another deer. (‘Akarabuvanam-Chidambara Rahasyam’, vv. 15-17)