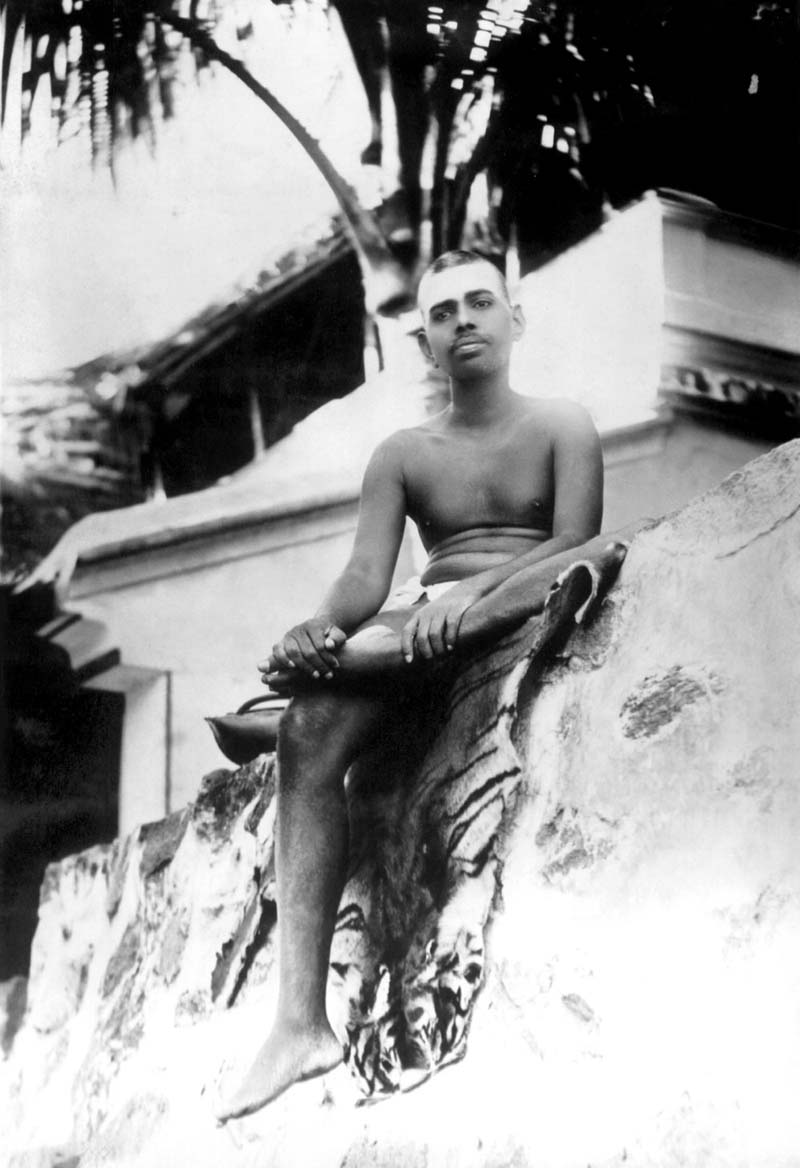

Yogi Ranganathan, Madurai

[This account is by Rangan, one of Bhagavan’s childhood friends. I included a chapter about him in The Power of the Presence (part one, pp. 1-38). I took the first few pages of my account from a chapter in one of Chalam’s books. Going through this Call Divine account, which I was not aware of when I compiled The Power of the Presence, I can see that Chalam himself used it extensively in his Telugu version.]

My father, an Inspector of Police, was transferred to Tiruchuzhi in 1885. Bhagavan’s father Sundaram Aiyar was then practising there as a vakil [unlicensed lawyer]. The two became close and intimate friends. I was a classmate of Bhagavan. My elder brother was in the same class as Bhagavan’s elder brother. Our two families moved on the friendliest terms, almost as close relations.

Around the middle of 1888 my father was transferred to another place and we left Tiruchuzhi. Bhagavan and his brother went to Dindigul for education and from there came to Madurai to continue their education. By that time we had also come to Madurai for our education. Bhagavan was first reading in the Mission School, whereas I was attending the Native College. However, the institutions were adjacent to each other. If my school closed earlier I would wait for Bhagavan; and if his school closed earlier, he would wait for me. I and my brother, along with Bhagavan and his brother, would go to the Vaigai River, play on the sands and return home. Other boys would join us. I was just one year older than Bhagavan. Bhagavan left Madurai in August 1896. After that, I didn’t see him again for a long time.

When I saw him for the first time in Tiruvannamalai, I was accompanied by my wife, mother and daughter. I asked Bhagavan whether he recognised me. His reply sounded as if he was speaking from the back of his throat.

‘Rangan,’ he croaked.

In those days Bhagavan spoke rarely, and he had almost lost speech through lack of practice.

Turning to Palaniswami, he pointed out my mother and asked him ‘Do you recognise this lady?’

‘Yes,’ he replied.

She had visited Bhagavan when he had been living at Pavalakundru in the 1890s. I spoke to Bhagavan for some time.

As I was taking leave of him I remarked, ‘You have attained a great stage’.

His reply was, ‘Distance lends enchantment to the view’.

I learned later from the many teachings that he gave to me directly, and from advice given to other people that I overheard, that he was implying ‘A householder’s life was as good as that of an ascetic, and could equally lead one to jnana’.

On my next visit, when I was still ten or fifteen steps from Skandasramam, Bhagavan, who was then cleaning his teeth near the parapet wall, observed my coming and told his mother, ‘Mother, Rangan is coming’.

She said, ‘Let him come. Let him come.’

When I got up after prostrating before Bhagavan, he said, ‘It is a rare privilege to get the darshan of saints. It is good to go and visit them frequently. They will weave the cloth and give it to you.’

From this I gathered that if one had Bhagavan’s grace one could gain jnana, even without any effort on one’s own part.

During my next visit, when Bhagavan, his mother and I were alone together, I told Bhagavan’s mother, ‘I have also a right to a share in all that Bhagavan has gained’.

Mother asked Bhagavan, ‘Did you hear what Rangan said?’ Bhagavan laughed and said, ‘Is he not also one of us? He has also a share.’

On another occasion I came to Bhagavan on my way to Madras where I wanted to try for a job.

When I got up after prostrating, Bhagavan asked me, ‘Men can go anywhere and somehow eke out a livelihood. But what arrangements have you made for your wife and children?’

I replied, ‘I have provided for them’.

I stayed for a few days with Bhagavan and then went away to Madras. A few days later my elder brother visited Bhagavan. Bhagavan made kind enquiries of him whether my wife and children were getting on well, without any hardship.

My brother had to tell him, ‘He left some money when he started for Madras. All that has been exhausted and they are now suffering great hardship.’

Then he continued his journey to Madurai.

When, after making some efforts for a job at Madras, I returned to Bhagavan, he asked me, ‘You told me you had provided for your wife and children. Your elder brother told me they are undergoing hardship.’

I did not make any reply. Why? Because Bhagavan knows all and is also all-powerful. I again went to Madras and, finding my efforts for a job there were in vain, returned to Bhagavan and stayed with him for some time.

During that time, one night, when I was sleeping outside on a double cot that was lying there, Bhagavan suddenly came and sat near my feet. Seeing this I got up.

Bhagavan asked me, ‘What is the matter with you? Are you restless and not getting sleep because of your family troubles? Would it he enough for you if you get Rs 10,000?’

I kept silent. Once when Bhagavan and I were going round the hill he said, ‘There are herbs on this hill which can transmute base metals into gold’.

That time too I kept silent. Bhagavan used to often joke with me and laugh, asking, ‘Oh, are you suffering very much?’

He then told me, ‘When a man sleeps, he dreams he is being beaten and that he is suffering terribly. All that would be quite real at the time. But when he wakes up, he knows it was only a dream. Similarly, when jnana dawns, all the miseries of this world will appear to be merely a dream.’

A few days later I returned to Madurai and through a friend got a manager’s job in a motor company. Later, I was also appointed as agent for the sale of buses in Ramnad and Madurai by another company, with a commission of 5% on all sales effected by me. From this and in other ways I got Rs 10,000, which I spent on clearing off my debts and marrying two of my daughters.

I never used to mention my family troubles to Bhagavan, nor ask him for anything. He was himself looking after me and my family. Why, then, should I make any requests for this or that particular thing? I left everything to him. It never occurred to me to ask him for any wealth.

I frequently used to tell Bhagavan, ‘I have entrusted my body, possessions, soul, all to you. The entire burden of my family is hereafter yours. From now on I am only your servant, doing only what you ask me to do. I am a puppet moved by your strings.’

Bhagavan would just laugh.

Once, at Skandasramam, when Bhagavan was standing, I felt his legs from the knee downwards, running my hands over them.

I remarked, ‘When in the old days we played together, I used to feel as if I was pricked with thorns whenever your legs came in contact with my body. Your skin in those days was rough and scaly. Now I find your legs are soft, like velvet.’

Bhagavan responded by saying, ‘My body has completely changed. This is not the old body.’

One day Bhagavan told me, ‘Let us go to Pandava Tirtham and swim in it. Can you still swim?’

I told him I had not forgotten and that I would be happy to go with him. The next morning, at 3 a.m., we went and swam there, playing as we did in the old days. We returned before people came there for their early bath.

Bhagavan said, ‘Let us do it again tomorrow. But we have to go early and return before people come there for their morning baths.’

I agreed and we went swimming there every morning for the next few days.

One day, before dawn, when I was restless in my bed, rolling from one side to another, Bhagavan came to me and asked, ‘Are you not getting sleep? What are you worried about?’

I told him, ‘I am thinking of taking up sannyasa. If I do it here my people would discover it. So, I want to go away to a distant place like Banaras and become a sannyasi there.’

Bhagavan went away and came back with a copy of Bhaktha Vijayam. He read from it the portion dealing with Vithoba’s determination to remain a sannyasi in a forest, along with the advice from his son Jnandev that the same mind goes with a man whether he stays at house or retires into a forest. He told me I could attain jnana while continuing to be a householder.

I asked Bhagavan, ‘Why then did you become a sannyasi?’

He replied, ‘That was my destiny’.

Then he added, ‘Though it is irksome to remain a householder, it is easy to attain jnana that way.’

Once at Skandasramam, after Bhagavan and I had taken a bath and he was drying his body with a towel, I noticed that from his knee to his ankle the skin had peeled off and blood was oozing. I asked him what the matter was with his leg. He said he didn’t know.

I asked, ‘Is it not your legs that blood is oozing from? You seem to know nothing about it!’

He replied very casually, ‘When I was sitting down, the fire from the charcoal brazier in which incense powder was being burnt might have burnt my skin and caused this sore’.

I at once sent for some ointment and applied it to his legs. From this I learnt how completely detached from the body Bhagavan was. He lived only in the Self.

One day, Bhagavan and I went round the hill by the forest foot path close to the foot of the hill. After I had gone a little distance on that path, which was full of thorns and sharp stones, I stepped on a thorn.

As I was lagging behind, Bhagavan observed me, came back to me, removed my thorn, and said ‘Now, we can continue’.

We carried on together but after a few yards he too stepped on a thorn. Noticing this, I ran up to him, lifted up his foot and saw the marks of several thorns there. I then examined his other foot and found several marks there too.

Bhagavan said, ‘Are you going to remove the new thorn or the old thorns?’

Then, with the greatest indifference, he pressed his foot on the ground, pushed it forward, and the thorn broke off. We then continued with our walk. It confirmed for me that he was living completely detached from his body. I further imagined that both of these incidents were somehow staged by Bhagavan to impress on me that he was not his body.

On another occasion Bhagavan said to me, ‘You think you are undergoing great troubles. Hear some of mine. I was once climbing the hill up a precipitous track and when I caught hold of a rock above me. The rock dislodged itself and I fell on my back. The moving rock dislodged others, all of which fell on top of me while I was lying on the ground. I managed to remove the rocks that were covering me and climb out. I found my left thumb was dislocated and hanging loose. I forcibly brought it back to its place and reattached it there.’

At that stage in the narration Bhagavan’s mother appeared and remarked, ‘Don’t ask for that horrid story. He came home with blood all over his body. It was too heart-rending a spectacle.’

I cannot understand who came and removed the rock, treated his wounds and fixed up the thumb. Who was that doctor?

One day Bhagavan’s mother told me in his presence that once, while he was standing, she saw various kinds of snakes all over his body, round his neck, chest, waist, legs. She became very afraid, but after some time the snakes all went back to their places. I believe that this was one of the visions vouchsafed by Bhagavan to his mother to wean her from the belief that Bhagavan was her son and to impress on her that he was God Himself.

Once, at Skandasramam, when Bhagavan, his mother and I were the only people there, mother told the following story: ‘About ten days ago, at about this time, ten in the morning, I was looking at Bhagavan. His body disappeared gradually and transformed into a lingam like the one in Tiruchuzhi Temple. The lingam was lustrous. At first I could not believe my eyes. I rubbed them, looked again, and still saw the same sight. I became afraid because I thought he might be leaving us. But slowly and gradually his body reappeared in place of the lingam.’

After hearing this account I looked at Bhagavan, who smiled at me. From this I gathered he was confirming his mother’s account. When I returned home I mentioned this to the members of my family. My eldest son, who was writing an account of what he called ‘Bhagavan’s marriage with his bride jnana’, included this incident in it.

Later, when that work was being read out before Bhagavan by my son and this incident came up, Bhagavan asked ‘Who told you this?’

My son, of course, replied ‘My father’.

Then Bhagavan said, ‘Oh, that fellow came and told you everything, did he?’

Some of the devotees who were listening to the work being read out asked what exactly was the incident referred to. Bhagavan dismissed it, saying it was nothing. I myself gathered from this vision of Bhagavan’s mother that Bhagavan was God himself, and that the vision was granted to mother to impress on her that she was no longer to think of him as her son, but as God Supreme.

One day, when Bhagavan and I were climbing the hill, I told him that because I have had the good fortune to have Bhagavan’s darshan, all my sanchita and agami karma had been burnt away like a bale of cotton by a spark of fire, and that only my prarabdha karma was left.

He replied, ‘Even prarabdha will remain only so long as the mind remains. If the mind is destroyed, to whom does the prarabdha belong? Think over that deeply.’

From that I understood that once the mind is killed and jnana is attained, there is no such thing as prarabdha.

Once a devotee who had behaved improperly towards Bhagavan asked me what he might do to expiate his offence. I advised him to do pradakshina round Bhagavan three times.

He walked around him three times, prostrated before him and said, ‘Bhagavan should not keep in his mind the mistake I have committed’.

Bhagavan replied, ‘Where do I have a mind? Only if I have a mind can I keep something there’.

It is clear from this that Bhagavan has attained mano nasa, extinction of the mind.

When Bhagavan was in Skandasramam, a gentleman from Malabar, greatly learned, and an expert in yoga sastras, came and lectured for four hours on yoga.

After he had finished, Bhagavan said, ‘Now, you have finished, I hope, everything that you wanted to say. The end of all your yoga is seeing lights and hearing sounds. The mind will be in laya (a suspension of mental activity) while the sound or light is there. When they disappear, the mind will again emerge. The real thing is to achieve mano nasa or extinction of the mind. That is what is called jnana.’

The other man said, ‘What you say is the truth,’ and took leave of Bhagavan.