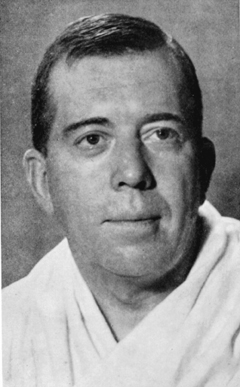

Sri Mouni Sadhu, Australia

Those who ‘knew’ Sri Bhagavan Ramana know him forever. This is because even a single encounter with the great rishi on our life’s path is an event that can never be forgotten or dimmed in our consciousness by the passage of time. For some of us, it meant a complete change in the course of our present and future lives, and this could never have happened otherwise.

The scope of the subject is far too broad to be described in detail within the framework of such a short article. I am therefore compelled to condense it as much as possible.

The first time I met him I had come directly from the cart that had brought me from the Tiruvannamalai railway station. Before visiting the ashram, I had been conversant with Sri Maharshi’s teachings for some four years and the many photographs I had seen had made his features quite familiar to me. When I was ushered into the dimly lit dining hall, I was therefore able to recognise him immediately, even though at that time his figure was much more meagre than in the pictures I had seen. He was sitting close to a wall, eating his evening meal. I bowed in greeting, and with an incomparable expression of kindness on his face, he asked me where the other devotee was who had come with me. I wondered at his very sharp memory because the letter announcing my proposed visit had been written many months before. My friend’s absence was explained; he had not been in a position to come. Sri Bhagavan then asked that supper be brought to me.

When I became conscious that at last I had found what I had been seeking all my life, this knowledge did not come through conscious deliberation but via an intuitive flash. I immediately became absorbed into the presence of the Master. At first I was worried about his precarious physical state, but my grief quickly became dissolved in his spiritual radiation. The outer appearance soon merged into that mysterious inner link with him that has remained unbroken from that moment up to the present time. While I was at his feet, I learned to stop the thought-current in my mind, a thing that formerly had devoured long years of effort, and which had never been completely successful, despite the many exercises of various occult systems. I never returned to those exercises; they were quite inadequate in the sublime spiritual atmosphere surrounding the Master, which in itself permitted much faster development.

The key to it – concentration – came of itself. Firstly, and most importantly, I became aware that there is a thing above all things that I had never known before. This cannot be adequately described in words, but nevertheless, perhaps some direct hints will give an idea about it. The eyes of the Master conveyed in silence that there is a state which is beyond and untouched by all human troubles, a state which is certainty and peace in itself, in which we know everything. For in that state everything is in us. This mysterious process in consciousness was induced by Sri Bhagavan, or rather by his presence, for he was himself all harmony and peace.

I tried to analyse the changes that arose in me when I meditated at his feet. I found that the mind was easily freed from thoughts, and that memory – in the usual meaning of the word – was no more. Also absent was the concomitant subdivision of time into past, present and future. Instead, there appeared something that cannot be properly described in words. Perhaps a conception of living eternity would be best. There were no visions but, strangely enough, one knew that there could be nothing unknown to him, for by completely directing the attention, one could know everything. These experiences have been more explicitly described in the book In Days of Great Peace.

In some wonderful way the Maharshi seemed to supervise these inner processes in us, just as an operator watches the work of complicated machinery that he knows thoroughly. Moreover, he mysteriously helped in these inner experiences, but how he did it still remains a mystery to me. At the same time, without any deliberation from my side, a potent love for him was created in my heart, simply because it could not be otherwise. Altogether, a man emerged from these experiences greatly changed and quite often with a totally different idea about everything in this world. I myself called it ‘the spiritual alchemy of the Master’. As time passed, I ceased to consider Sri Bhagavan as a being of flesh and blood. This was the most wonderful experience and conquest. From that time on the Master could never be lost to me, although I was only too well aware that his days on this earth were numbered and few remained. I saw the spiritual essence of the man, the indestructible core instead of just the mortal frame. This was the chief factor that enabled me to bear his physical departure without any inner catastrophe.

The word ‘spirit’ is plainly misused by a world that cannot connect the term with anything real, often confusing it with emotional and mental impressions, creating from them an idea of something indefinite and dim. All his long life Sri Maharshi taught that the true reality is beyond all forms, no matter to which plane of existence they belong. And yet, for many people this remains merely a myth or theory. After the Master left this earth, I tried to analyse what it was in his manifestation amongst us that was the most important thing for future generations to remember him for. I reached the conclusion that it was that he himself showed the example of what final attainment is, thereby making it accessible to everyone else. An eternal wisdom lies in all his utterances. He confirmed the truth of them by being that wisdom himself. For example, Maharshi demonstrated that he was not the body and that his true Self never suffered when that body was attacked by a painful disease, one that would be terrifying for an average person to undergo. However, we all felt that, though he was detached from his bodily pains, he could have overcome the disease if such an outcome had been necessary.

When such a sage testifies to the immaterial truth of being, and daily pointed us all towards it, how could I ever seek something apart from it? The Maharshi himself knew very well the decisive role he played in the lives of those who were fortunate enough in their karmas to come to him from all sides of the world.

He says, ‘Association with the sages who have realised the truth removes material attachments. These attachments being removed, the attachments of the mind are also destroyed. Those for whom attachments of the mind are destroyed become one with That which is ever motionless. They attain liberation while yet alive. Cherish, therefore, the association with such Sages.’

Such a sage was and is Sri Ramana, and there are many of us who used to know and revere him.

M. K. S., Karachi

No man can be happy without the knowledge of God. Scriptures are our guides in the path to the Godhead. It is said in the Bible, ‘Many are called but few are chosen’. Religion is essential for all. Man needs spiritual bread for his sustenance in the struggle of life. A stage arrives in the evolution of a human soul when man is not satisfied with mere teachings and promises of a life hereafter. He longs for God. He thirsts for God. He gets intoxicated in his love of God. He sets aside his Bible, his Koran, his Gita, his Gathas. He wants to see God face to face. He yearns and pines for his visual revelation. He discards everything in life. He is prepared to go through all the trials, tests and ordeals that may be necessary for attaining the object of his heart. He starts on the journey in the quest of truth. He yearns to unravel the secrets of the universe and be merged in God.

In July 1947 I was ordered by my Spirit Master to pay a visit to Tiruvannamalai and sit at the feet of the Sage of Arunachala, Bhagavan Sri Ramana. The journey was long but the longing to see the sage was greater. Accompanied by my wife, we embarked upon the journey, a distance of more than two thousand miles by rail. Passing through Bombay and Madras we arrived at Sri Ramana’s ashram with hearts gladdened by the prospect of attaining spiritual enjoyment. We arrived when the moon was shining in the sky, casting its shimmering, pale, silvery light through the foliage of trees, through which we passed to reach our destination. It was all so quiet.

We stayed in a cottage, named ‘Detachment’. The very name of the cottage was enough to send thrills of delight through every nerve and fibre of our being. It appeared God was preparing in His subtle manner for the great future that was awaiting.

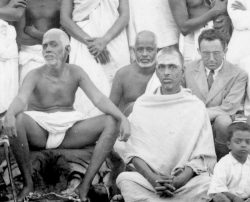

The next day we were in the presence of the sage in the hall. Prostrating at full length, we sat near him on the floor. My friend Doraiswami, the Honorary Secretary of the Spiritual Healing Centre, Coimbatore, had also accompanied us from Madras. As I sat for hours and hours together without being fatigued or exhausted in that hall, with many other devotees squatting on the floor, my eyes were rivetted upon the magnetic personality of the sage. Naked, except for a loin cloth that he wore, his face kindled with the fire of the inner light, his deep, searching eyes that seemed to penetrate into the soul of every devotee gathered in that silent throng, his majestic look, his tall frame made slender by the years of abstinence and tapas practised in the forests and the caves where he communed alone with his God – all this made a deep impression upon our minds.

Sri Ramana appeared to be the very soul of India. This country has been known as a land of rishis. And it is India’s pride that in spite of the wave of materialism that is sweeping all over the world, this tradition of her spirituality has been maintained so beautifully. In fact, India’s greatest contribution to the world is her spirituality. We are living in an age of rush and crash. Passivity is decried and activity is hailed as a mark of progress in all phases of life. We do not deny the role of human activity in the economy of life. But it is incorrect to say that passivity is alien to progress and that it is tantamount to sin. The life of the sage of Arunachala is a most salient and solid rejoinder to this vile accusation. This man lived all his life in the vicinity of Arunachala. He lived a life of silence, seclusion and solitude, away from the maddening crowds, in utter renunciation, and he realised God. God-realisation is the only real goal of life.

This is lost sight of by westerners, and passivity is wrongly criticised. By passivity, we mean, passivity of the right type, when man yearns for God and in his yearning, he is prepared to forego everything and seeks Him by the marga of silence, seclusion and deep meditation. Ramana left his home, when he was just a lad studying in a school, when the longing came to him to give himself up solely to God. He went in search of his Lord and found Him in the seclusion of his heart in the midst of surrounding quietude of nature, away from the dust and din of a skeptic world steeped in ignorance of God’s light and beauty. To sit at his feet in that silent hall vibrant with the radiance of his soul pervading the whole atmosphere was a feast for the soul.

Devotees of various classes come for his darshan. Some come in the hope of solving their difficulties. Some come for his blessings. Some come out of sheer curiosity. Some come with an understanding heart, that the sage in his invisible, subtle manner, would kindle a fire and let loose the soul from the bondage of the body. I was fully aware that this miracle would be performed by him.

On the last day, before bidding adieu to the Sage, I sat for a long time, squatting on the floor and lo! to my surprise, I fell into a sort of samadhi – the first of its kind experienced. It was like awakening in a new world. It was all rapturously divine. The sage had worked his miracle. The secret purpose of my visit was understood. He opened the inner valves and gave me freedom. My soul was free. I left the sage of undying fame and his ashram with a heart bounding with joy and bursting with gratitude.

Sri M. S. Madhava Rau, Mangalore

My claim to write is that of one who saw Him. I dare not say ‘I know Him’. Twice I and my wife had the beatific privilege of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi’s darshan, with a space of ten years intervening. A decade after the last visit I am now writing of the deep and abiding impression he made on me.

My first visit was in the company of Maurice Frydman from Bangalore. Suddenly one morning, early in 1934, he said that he was going to Tiruvannamalai that night. He asked us if we would like to accompany him. He had been there many times before but never invited us. Nor had we ever thought to ask if we could accompany him. This time, though, the question and our own wishes were beating in unison.

The offer came at an unfortunate moment since we didn’t at that time have the money required for the trip. However, almost immediately, the post brought a letter from relations in Mangalore asking us to meet that day a person to whom some of our articles had been sent. We called on her and received the parcel. Inside, among other things, was an envelope containing some currency notes. An accompanying note said that in the haste and confusion of our departure from her house a few months earlier this money had been left in a cupboard in their home. We counted it out and discovered that the newly acquired sum would be just sufficient for a trip to Tiruvannamalai and back. And so we went with Maurice.

At the ashram Maurice introduced us to the Maharshi. He welcomed us with a gracious smile and made enquiries about where we were from. When we replied ‘Mangalore’, the Maharshi said that M. S. Kamath (of the Sunday Times) was a frequent visitor to the ashram. He then told the other people in the hall a few interesting tidbits about the languages, customs and so on of that part of the country. When he learnt from us that for some years we had lived and worked in the Theosophical Society, Adyar, he smiled again and said that we would then easily make ourselves at home in the ashram. And we did, very happily too.

The Maharshi’s serene and busy life reminded us of Dr Annie Besant in several respects. In the evening a visitor arrived, a big and prosperous-looking Punjabi Sikh gentleman, dressed completely in European clothes. Noting his discomfort while he was attempting to perform the full pranam that Indian etiquette requires, the Maharshi immediately set him at rest, saying it was unnecessary. He also arranged for a chair for him to sit in. The gentleman said plaintively that he was pining for peace of mind. The Maharshi asked who it was that was pining. The visitor was puzzled. In humble and anxious tones he pleaded that he was too ignorant and busy for such deep introspection. However, he added that he would be grateful for some japa, prescribed in the Maharshi’s own words, and conveyed with his blessings. He promised to do the japa in whatever spare time he had.

The Maharshi told him that devoting the same amount of time he had to spare for his japa to enquiry instead would be more beneficial, and that, with practice, it would amply repay his efforts and could even be done at the times when he was busy at work. This was not what the Sikh visitor wanted to hear. After he had failed in his repeated attempts to persuade the Maharshi to give him some japa, he asked, sadly, whether, having come with such high hopes, the Maharshi was now going to send him away empty handed. The Maharshi assured him in a compassionate way that he should not think in this way.

The following morning the Maharshi cited some verses to the Sikh visitor that came from an edition of Yoga Vasishta that had been printed by Maurice Frydman. This appeared to revive his spirits and he left for his train in a good mood.

That evening Frydman and I took Bhagavan’s permission to return to Bangalore and come back. Bhagavan repeated the ‘come back’ part of the request in an affectionate and slightly quizzical way. We did come back, but not for another ten years.

In 1944 my wife and I came with Mr and Mrs Sanjiva Rao. That time we put more planning and organisation into our trip. The ashram premises and the neighbourhood around it had expanded immensely in our absence. There were many more visitors, and more ashram activities had been added. The Maharshi had clearly advanced in age. He looked much older, and he had grown weak as well. We spoke to Dr K. Shiva Rao about it and he confirmed that Bhagavan’s health was in decline. We were told that he consistently refused to take any special food that might improve his condition, saying that he would only take what was offered to everyone else in the ashram.

We were introduced to him again. He looked at us and said that the introduction was superfluous since we had been introduced by Frydman many years before. He remembered us. Life in the hall was more active and varied than on our earlier visit. There were numerous visitors who had come from all over the world. Mothers frequently brought their babies for a blessing, which he bestowed on them with a tender smile. The morning and evening prayer times were silently vibrant with a power that stirred and pacified one’s innermost being. People mostly sat quietly or meditated, and as they did so Bhagavan’s eyes would impersonally scan the room, imperceptibly alighting for a moment on the people who were sitting there. Animals came and went freely and often left with food given by Bhagavan himself. One day I saw a brahmin woman, dressed in rags, come into the hall and begin to wail in a pitiful way. Bhagavan rose from his seat and met her half way. He enquired about the cause of her misery and learned that she was an ill-treated and abandoned wife who had been driven from her home. Bhagavan asked her to stop crying and invited her to sit down and have a rest. She followed his advice and shortly afterwards looked consoled and calm.

On one afternoon there was discussion among a small group over an ignorant questioning of the Maharshi’s teaching in some British or American philosophical journal. The Maharshi joined in with a few brief remarks, and resolved the doubts of those who had raised questions about the contents of the article. He ended the discussion in a humorous way, speaking partly in English and partly in Tamil, by saying, ‘Indian philosophy begins where western philosophy ends’.

The sublime and the mundane were readily mixed. Early one morning he was making a joke about a laxative he had concocted himself. He said that one devotee, in an excess of zeal, had taken an overdose and paid for it by having no rest for several hours.

One experience impressed itself on me indelibly. Before beginning meditation in his presence, I decided that at some point during that day I should ask the Maharshi about a personal problem I had been agonising over for some time. As I sat there meditating, the answer flashed before me, and along with it I was filled with an indescribable flow of happiness. Without needing to vocalise the problem to him, I had received both an answer and the experience of his power and grace. This experience in his presence was sufficient for me to sense the truth of both his message and his silent teaching.