Viorica Weissman Interviews David Godman

Page 2

Question: Your journey to Tiruvannamalai shows a strong determination to reach Ramanasramam. When you were asked how long you wanted to stay in the ashram, you answered ‘A few weeks’. What where your plans and expectations about those few weeks you intended to spend there? Did you have any? How did you see your future life in India at that time? What was it that you were really looking for? How did things really turn out to be? I ask because those ‘few weeks’ actually extended to a life time.

Answer: I don’t think I had any expectations because I had no idea what to expect. The period of ‘a few weeks’ was a bit arbitrary. I didn’t think I could afford to stay there much longer, and I definitely didn’t go there with any idea of settling down. I had a gap of a few months in my life, some money in my pocket, and a desire to connect with Bhagavan.

I had spent most of the previous year in Ireland, doing self-enquiry in a small rented house, and growing most of my own food. I had to give up living there because my landlady, who had gone to live in Australia with her husband, wanted to reclaim it. Her husband had had a major accident, and with no medical insurance, she needed to sell the house to pay his bills. I then went to Israel for a few months, primarily because I didn’t want to have a cold and wet winter in the UK or Ireland. My plan was to return to another house in Ireland once I had finished my spell in Israel and completed my pilgrimage to India.

What was I looking for? I don’t think I was looking for anything. I just felt an irresistible urge to come to Tiruvannamalai to connect with the place where Bhagavan lived most of his life. In retrospect it seems such an odd and bizarre thing for me to have done. I am sure I had reasons at the time that made perfect sense to me, but looking back on that period I can’t recollect any sensible ones.

With hindsight I would say that Arunachala pulled me here, and that whatever reasons I might have had at the time were just my mind’s attempt to construct a coherent narrative and justification for what was going on.

I remember Bhagavan telling a visitor once that it was the power of Arunachala that brings everyone here, including him. Our brains might think of a sensible reason or excuse to go to Arunachala once that power has manifested, but it is the pulling power of the mountain that is the real cause of our journey.

Some of us have a script, a prarabdha, to be here. The body and mind will feel the pull, start moving in this direction, after which we think up a rational reason to justify the trip.

There have been some interesting experiments in neuroscience in the last few years. It is possible to monitor the parts of the brain that make the body do things, while simultaneously checking other corners of the brain that take the decision to perform the actions. Much to the scientists’ consternation, it has been discovered that the body starts to perform an act a few seconds before the decision to do it manifests in the brain. This has rather alarming implications for our belief in free will. It seems that the body has a script, that it starts executing its actions before the ‘I’ inside us ‘decides’ to do them. If the experiments stand the test of time, they really will demonstrate that the ‘I am the doer’ idea is an artificial construct, one that is there merely to sustain the mistaken idea that we are in charge of our destiny, and that we can choose and decide the things we do in this life.

So, some power drew me here and kept me here, and my mind had to run along behind, justifying it.

It didn’t take me long to fall in love with this place. Quite early on I knew that I wanted to stay in this place as long as possible. Again, I don’t know why. However, in opposition to this there was a recurring feeling: ‘I don’t have much money. Sooner or later I will have to go home.’

Destiny had other plans, though. At some point in my first year here I was walking around Bhagavan’s samadhi when it suddenly dawned on me, ‘I don’t have to go home. This is my home. I don’t need to go anywhere at all.’

It was like a great weight being suddenly lifted off my shoulders. I didn’t need to go anywhere because I had found my way ‘home’.

When I lived in Lucknow there was a woman there called Almira who had come from Hawaii to be with Papaji. She had come for a few weeks, wanted to stay longer, but had a plane ticket that had to be used within a particular time.

Me, Papaji and Almira in Lucknow, 1996

When she told Papaji about this, he just said, ‘Your ticket has expired’.

‘No,’ she said, ‘it’s still valid. I can show you.’

He refused to look at it when she produced it. When she attempted to get him to read the date, he waved it away. He just repeated his earlier pronouncement: ‘Your ticket has expired.’

Eventually, Almira took the decision that she was going to let her ticket run out and stay on in Lucknow.

When she told Papaji of her decision, he said, ‘See, I told you. Your ticket has expired.’

The expiry had nothing to do with the calendar. Papaji just knew that she was destined to remain in Lucknow. She stayed more than five years and didn’t leave until after Papaji had passed away.

I didn’t have a ticket printed on a piece of paper, but I did have a similar fixed idea that I would have to leave within a few weeks of my arrival. I had put aside enough money to get back to the UK and assumed I would have to buy a ticket to return there once I had no more money to support myself in Tiruvannamalai. That moment in the samadhi hall dissolved a self-imposed layer of mental agitation: that I would have to leave when I didn’t want to, and that my time at Arunachala was limited.

I think all of us waste a lot of time and energy agonising over choices and decisions in our lives because we think we are in charge of what happens to us, and we further believe we have to plan and scheme to change the circumstances in our lives, or keep them the way they are.

Ramaswami Pillai once asked Bhagavan, ‘Life is full of apparent choices. We waste a lot of energy thinking about what we should do. When a choice presents itself, how can we tell if it is something that we have to do, or whether it is something that will waste our time and lead us in the wrong direction.’

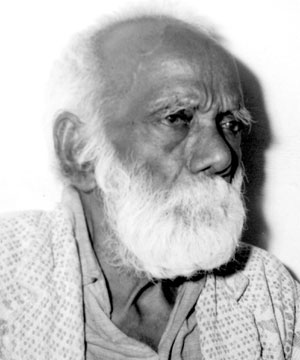

Ramaswami Pillai

Before I give Bhagavan’s reply I should say that in Tamil Nadu destiny is often conceived as a load that one carries on one’s head.

Bhagavan told him, ‘Throw it down three times. If it jumps back three times, then it is something you have to do.’

If we have a mind, we can’t tell what things are destined for us. A jnani might see and know, and he might even tell us if we are lucky. The rest of us just stumble along, making plans and thinking we are in charge of future events.

I was destined to be in Tiruvannamalai. Hindsight alone tells me that. I ‘threw it off my head’ a few times, but it always jumped back. On several occasions I made attempts to be somewhere else, but they never worked out for long. Sooner or later I would always find myself back at the foot of Arunachala.