‘Which commandment is the first of all?’ [asked a scribe]. Jesus answered, ‘The first is ”Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one; and you shall love the Lord your God will all your heart and will all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength”. The second is this, ”You shall love your neighbour as yourself”. There is no commandment greater than these.’ (Mark 12:28-31)

In giving this answer Jesus was repeating and embellishing on the great Jewish proclamation of faith and practice that was originally given to the Israelites by Moses (Deuteronomy 6:4-5):

4 Hear O Israel: the Lord our God is one Lord;

5 And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul and with all your might.

The word ‘Lord,’ mentioned three times in these two verses, is, in the original Hebrew, Yahweh, the term the Jews used to denote the ‘I am’ who revealed Himself to Moses. In addition to this rendering, which I have taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, three other readings can be regarded as acceptable translations:

a) Hear O Israel: Yahweh, our God, Yahweh is One.

b) Hear O Israel: Yahweh is our God, Yahweh is One.

c) Hear O Israel: Yahweh is our God, Yahweh.

Once one knows that Yahweh denotes God as ‘I am’, the significance of the following verse becomes more apparent; ‘and you shall love Yahweh, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your might’. That is to say, both Moses and Jesus were saying, indirectly, that heart, soul and mind must be directed exclusively and lovingly towards the ‘I am’ that is God. Jesus said that there was no greater commandment than this, and Moses, emphasising the same point, went on to tell the Israelites:

And these words [Deuteronomy 6:4-5] which I command you this day shall be upon your heart; and you shall teach them diligently to your children and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down and when you rise. And you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. And you shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates. (Deuteronomy 6:6-9)

In fulfilment of this command, orthodox Jews attend their synagogues wearing phylacteries on their foreheads and hands that contain copies of these verses from Deuteronomy. They also have copies in special containers that are attached to their door and gateposts. Some devout Jews even kiss the container reverently each time they enter and leave as a gesture of respect towards Yahweh, the one God who revealed Himself to Moses as ‘I am’. Verse four in particular is the greatest and most widespread affirmation of faith for all Jews. Whatever their mother tongue, and irrespective of what country they live in, all practising Jews regularly recite verse four in the original biblical Hebrew.

The sadhana of loving God as He really is, as ‘I am,’ with all one’s heart, having rejected all other thoughts, is identical to the path of true devotion as taught by Bhagavan on many occasions:

Question: That is why I am asking you whether God could be worshipped through the path of love.

Bhagavan: … Love itself is the actual form of God, If by saying, ‘I do not love this, I do not love that,’ you reject all things, that which remains is swarupa, that is, the real form of the Self. That is pure bliss. Call it pure bliss, God, atma or what you will. That is devotion, that is realisation, that is everything.

If you thus reject everything, what remains is the Self alone. That is real love. One who knows the secret of that love finds the world itself full of universal love. (Letters from Sri Ramanasramam, 2:39)

Jesus instructed his followers that they should not merely love God with all their heart, they should also love their neighbours as themselves. Here Bhagavan is saying that this automatically happens when the first commandment, loving God with all one’s heart, is fulfilled. When one experiences ‘Love … the actual form of God’, the world itself, including all possible neighbours, is experienced as one’s own Self, and is found to be ‘full of universal love’.

The experience of not forgetting consciousness [‘I am’] alone is the state of bhakti, which is the relationship of unfading real love, because the real knowledge of Self, which shines in the undivided supreme bliss itself, surges up as the nature of love. Only if one knows the truth of love, which is the real nature of Self, will the strong entangled knot of life be untied. Only if one attains the height of love will liberation be attained. Such is the heart of all religions. The experience of Self is only love, which is seeing only love, hearing only love, feeling only love, tasting only love and smelling only love, which is bliss. (Guru Vachaka Kovai, vv. 974, 652, 655)

I should not like to give the impression that the interpretations I have given represent the teachings of any major Church or denomination I know about. However, much to my surprise, the Pope devoted his Easter message in 1992 to an explanation of some of ‘I am’ quotes in the Bible. I heard it live on the radio in my room at Sri Ramanasramam and found it to be a stunning example of synchronicity since I was compiling this article at the time. When I discovered that none of my local Catholic churches had received a copy, I wrote to the Vatican directly, expecting to receive the official version of this speech, along with a covering letter from a minor official. Instead, several months later, I received a rather charming letter that stated, ‘His Holiness has been very busy lately and regrets the delay in answering your letter. Enclosed is a copy of his Urbi et Orbi [To the city and to the world] Easter address that you requested.’

URBI ET ORBI ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS POPE JOHN PAUL II

EASTER SUNDAY

(19 April 1992)

1. “I Am” (Jn 8:24).

The women went to the tomb;

they found it empty

and heard the message: He is not here!

Why do you seek among the dead him who is alive?

He has risen! (cf. Lk 24:5-6).

“I Am”.2. Long before, Moses had asked God his Name:

“I am who am” – came the reply

from the burning bush (Ex 3:14).

I AM – the name of God, of “Yahweh”.

And Jesus said to the children of Israel:

Before Abraham was, I AM” (Jn 8:58)

– and then they tried to stone him.

He also said:

“When you have lifted up the Son of man,

then you will know that I AM” (Jn 8:28).

Then they lifted up the Son of man on the Cross

and, when he was already dead,

they struck his side with the lance

and placed his lifeless body in the tomb.

But on the third day, early in the morning,

from the empty tomb comes the confirmation: I AM.

The life and death of the Son of man

are rooted in the immortality

of HIM who IS.3. “I am with you”.

These are Christ’s words to the

and he sends them put into the whole world

to preach the Gospel to all peoples (cf. Mk 16:15).

He sends them out poor and vulnerable.

He says: “You shall be my witnesses” (Acts 1:8).

Take nothing for your journey (cf. Mk 6:8).

Having the witness of the Resurrection and the life

you have everything: I AM with you

“Woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel”

exclaims the Apostle (1 Cor 9-16) … Woe to me!

“The love of Christ controls us!” (2 Cor 5-14).

What other good news could there be,

apart from this, that Christ died

for the sins of all and rose again?

That in him mortal human life

has been rooted in the immortality

of HIM who IS?4. “I AM with you”.

From these words began

all the apostolic journeys,

all the missionary travels

which have carried the Gospel into the whole world.

“I AM with you”:

Although the Pope chose this subject for one of the key speeches in the Catholic calendar, mainstream Christianity has never taught that God can be approached by abiding in the inner feeling of ‘I am’. Those who have advocated such practices have only ever been in a small minority, and they have usually been regarded with deep suspicion by more orthodox members of the Church.

I should like to discuss in the last portion of this article the views and experiences of one man from this small minority who, though a committed Christian, found in the Bible’s ‘I am’ statements a major revelation. They indicated to him both a way to attain union with God and at the same time provided him with a bridge between Christianity and Vedanta.

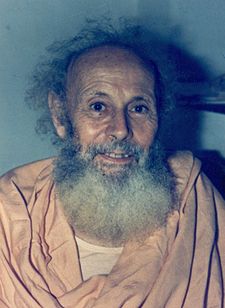

Swami Abhishiktananda was a Benedictine monk and priest who spent twenty years in a French monastery under his original name and title, Father Henri le Saux. He came to India in the 1940s and soon fell under the spell of Ramana Maharshi. His experiences at Sri Ramanasramam in 1949 presented him with a challenge, the resolution of which was to occupy his mind and heart for twenty-five years. The first few quotes are from Saccidananda, by Swami Abhishiktananda, published by the ISPCK in 1974:

In its own sphere, the truth of advaita is unassailable. If Christianity is unable to integrate it in the light of a higher truth, the inference must follow that advaita includes and surpasses the truth of Christianity, and that it operates on a higher level than that of Christianity. There is no escape from this dilemma. (p. 48)

Swami Abhishiktananda came to feel that Christians and Hindus, divided by differing and contradictory theologies, could only meet on equal terms in the ‘cave of the Heart’. In this ‘place’ the followers of both religions could experience the ‘I am’ of God’s real nature: ‘Deep in his heart, the Indian seer heard with rapture the same ‘I AM’ that Moses heart on Mount Horeb.’ (p. 94)

In my own depth, beyond all perceiving, all thought, all consciousness of distinction, there is the fundamental intuition of my being, which is so pure that it cannot be adequately described. It is precisely here that I meet God, in the mystery at once of my own being and of His … In the last resort, what can I say of myself except that ‘I am’… Just so, all that I can truly say of God is simply that ‘He is’. This is what was revealed to Moses at Horeb, and it was also realised intuitively by the rishis: ‘It is only by saying ”He is” that one may reach him.’ [Katha Upanishad 6:12] He is – nothing more can be said of Him. (pp. 167-8)

Christianity teaches that God is a Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and that the three will always remain three even in the final experience of ‘I am’. It also teaches that God can never be fully known in the way that He knows Himself, so knowledge of Him can only ever be partial. Abhishiktananda initially accepted this idea – he was after all a Catholic priest – and speculated that the final ‘I am’ experience for a Christian must necessarily be a Trinitarian one in which God was not fully known:

The mysterious name which the Lord had revealed was beyond all human comprehension. The reply ‘I am who I am’ meant that the Name is permanently withheld from the merely curious enquirer, but at the same time, for the earnest seeker who is moved by love, it constitutes a precious invitation to penetrate to the very heart of the One who essentially is. Yahweh is indeed the name which reveals God, and at the same time conceals Him. (p. 2)

… it is a call to the deepest recesses of the human spirit, a call which itself comes from the secret cave of the heart where alone man is really himself. The call is the most powerful reminder that the name of God is indeed mysterious, as the Bible says, that reason alone is incapable of apprehending God, that he remains essentially the Inaccessible One. (p. 10)

In unveiling for man the secret of God, he [Jesus] reveals the last secret of man’s own being, the secret that his own origin lies deep within God’s infinite love. At the very heart of the dazzling glory of being, he reveals to man the even greater glory of the love in which Being, ‘He-who-is’, has within himself a three-fold communion with himself. (p. 100)

At this stage of his search Abhishiktananda was saying that the ‘I am’ that the rishis experienced was not the highest state. Beyond this, he said, there is the Christian experience of being in which one knows and experiences God as a Trinity. This conclusion was a natural consequence of his dilemma, stated earlier, that Christians must integrate advaita in the ‘the light of a higher truth’ or concede that the truth of advaita ‘surpasses the truth of Christianity’. According to Abhishiktananda, in this final state of being there is an awareness of the sharing and the intermingling of the three distinct Persons of the Trinity:

The mystery of the Holy Trinity reveals that Being is essentially a koinonia [a fellowship or sharing] of love; it is a communion, a reciprocal call to be; it is being-together, being-with, co-esse [Latin for ‘to be with’]; its essence is a coming from and a going to, a giving and receiving. (p. 135)

The book I have taken all these quotes from, Saccidananda, expounded a view of Christianity that is called ‘the theology of fulfilment’. Simply stated, it is the belief that everyone in the world, at some distant future date, will become a Christian. It is underpinned by the belief that the fullest revelation of God can only be had within a Christian framework, and that while other religions may contain interesting and even holy ideas, the practical application of them cannot result in the highest knowledge of God that is available to a Christian. Thus Abhishiktananda could write that a ‘Christian jnani‘ (an oxymoron in my opinion) would have a Trinitarian experience of ‘I am’ that would be superior to the ‘I am’ experiences of Hindu sages. This attitude enabled him to write, without feeling at all patronising, ‘India become Christian would surely feel a quite special attraction to silent meditation on the name of Yahweh‘. (p. 94)

Towards the end of his life Abhishiktananda finally had, as a consequence of a heart attack that left him temporarily paralysed on a street in Rishikesh, a full realisation of ‘I am’ which, judging by his description of it, seemed to convince him that his previous attempts to fit it into a Trinitarian framework were presumptuous These quotations come from an edition of his letters that was published posthumously (Swami Abhishiktananda, by James Stuart, ISPCK, 1989):

Who can bear the glory of transfiguration, of man’s dying as transfigured; because what Christ is I AM! One can only speak of it after being awoken from the dead … It was a remarkable spiritual experience … While I was waiting on my sidewalk, on the frontier of the two worlds, I was magnificently calm, for I AM, no matter what in the world! I have found the GRAIL! (p. 346)

The finding of the grail was inextricably linked to losing all the previous concepts he had had about Christ and the Church. Commenting on this experience, he said, ‘So long as we have not accepted the loss of all concepts, all myths – of Christ, of the Church – nothing can be done.’ (p. 358) From this new experiential standpoint he was able to say, from direct experience, that it was the ‘I’, rather than a collection of sectarian teachings and beliefs, that gave reality to God:

I really believe that the revelation of AHAM [‘I’] is perhaps the central point of the Upanishads. And that is what give access to everything; the ‘knowing’ which reveals all ‘knowing’. God is not known, Jesus is not known, nothing is known outside this terribly solid AHAM that I am. From that alone all true teaching gets its value. (p. 356)

In addition to writing several books that attempted to bridge the gap between Hinduism and Christianity, Abhishiktananda was a regular contributor to seminars and conferences on the future development of Indian Christianity. After his great experience he received an invitation to attend a Muslim gathering in France to give a Christian point of view. In declining the invitation he revealed how all his old ideas had been swept away and how he no longer felt able to expound a specifically Christian viewpoint:

The more I go [on], the less able I would be to present Christ in a way which would still be considered as Christian … For Christ is first an idea which comes to me from outside. Even more after my ‘beyond life/death experience’ of 14.7 [.73] I can only aim at awakening people to what ‘they are’. Anything about God or the Word in any religion, which is not based on the deep ‘I’ experience, is bound to be simple ‘notion’, not existential.

Yet I am interested in no Christology at all. I have so little interest in a Word of God which will awaken man within history … The Word of God comes from/to my own ‘present’; it is that very awakening which is my self-awareness. What I discover above all in Christ is his ‘I AM’ … it is that I AM experience which really matters. Christ Is the very mystery ‘that I AM’, and in the experience and existential knowledge all Christology has disintegrated. (pp. 348-9)

Then, confirming that a lifetime’s convictions had been dropped, he went on to explain that the final Christian experience of ‘I am’ could not differ from its Hindu equivalent:

What would be the meaning of a ‘Christianity-coloured’ awakening? In the process of awakening all this colouration cannot but disappear … The colouration might vary according to the audience, but the essential goes beyond. The discovery of Christ’s I AM is the ruin of any Christian theology, for all notions are burned within the fire of experience … I feel too much, more and more, the blazing fire of this I AM in which all notions about Christ’s personality, ontology, history etc. have disappeared. (p. 349)

After a lifetime of meditation and research he had finally conceded that no explanation or experience could impinge on the fundamental reality, ‘I am’, which was revealed to Moses by God. Years before he had predicted that this standpoint would be the inevitable consequence of a full experience of ‘I am’. Perhaps even then he was having doubts about the theology of fulfilment and its premises that only through Christianity could the highest experiences be attained. The final quotes are from one of his early books (Saccidananda, by Swami Abhishiktananda, ISPCK, 1974):

Doctrines, laws and rituals are only of value as signposts, which point the way to what is beyond them. One day in the depths of his spirit man cannot fail to hear the sound of the I am uttered by He-who-is. He will behold the shining of the Light whose only source is itself, is himself, is the unique Self … What place is then left for ideas, obligations or acts of worship of any kind whatever? (p. 46)

When the Self shines forth, the I that has dared to approach can no longer recognise its own self or preserve its own identity in the midst of that blinding light. It has, so to speak, vanished from its own sight. Who is left to be in the presence of Being itself. The claim of Being is absolute … All the later developments of the [Jewish] religion – doctrine, laws and worship – are simply met by the advaitin with the words originally revealed to Moses on Mount Horeb, ‘I am that I am’. (p. 45)