Rob Sacks: I often wonder whether Westerners misunderstand Ramana Maharshi. What are the most common misconceptions about his teachings?

David Godman: I am not sure how much understanding there is of Ramana Maharshi and his teachings in the West. He is an iconic figure to a vast number of people who are following some sort of spiritual path. I think that for many people he epitomises all that is best in the Hindu Guru tradition, but having said that, I think that very few people know much about him, and even fewer have a good grasp of his teachings. Not many people read books about him nowadays — I know that from trying to sell my own — and even fewer would profess themselves to be his devotee. I find there is very little interest in his teachings even among the people who come to visit Ramanasramam. Nowadays, many of the people who come are spiritual tourists, pilgrims who just travel round India, checking out all the various ashrams and teachers. About twenty years ago I met a foreigner here who had come to the ashram for advice on how to do self-enquiry properly. For several days he couldn’t find anyone who was practising it, even in Ramanasramam. The people he asked in the ashram office just told him to buy the ashram’s publications and find out from them how to do it. Eventually, he had what he thought was a bright idea. He stood outside the door of the meditation hall at Ramanasramam, the place where Sri Ramana lived for over twenty years, and asked everyone who came out how to do self-enquiry. It transpired that none of the people inside were doing self-enquiry. They came out one by one and said, ‘I was doing japa,’ or ‘I was doing vipassana,’ or ‘I was doing Tibetan visualisations’.

How can there be misunderstandings among people who have never even bothered to find out the teachings in the first place, or put them into practice?

Rob Sacks: I think that some people who are now teaching in the West are creating misunderstandings about his teachings. Some of them seem to confuse glimpses of non-duality and feelings of relative selflessness with Self-realisation. Since a number of these teachers trace their lineage back to Sri Ramana, their students project the ideas of these teachers onto Sri Ramana. What do you think about this?

David Godman: What are Sri Ramana’s teachings? If you ask people who have become acquainted with his life and work, you might get several answers such as ‘advaita‘ or ‘self-enquiry’. I don’t think Sri Ramana’s teachings were either a belief system or a philosophy, such as advaita, or a practice, such as self-enquiry.

Sri Ramana himself would say that his principal teaching was silence, by which he meant the wordless radiation of power and grace that he emanated all the time. The words he spoke, he said, were for the people who didn’t understand these real teachings. Everything he said was therefore a kind of second-level teaching for people who were incapable of dissolving their sense of ‘I’ in his powerful presence. You may understand his words, or at least think that you do, but if you think that these words constitute his teachings, then you have really misunderstood him.

Rob Sacks: There are some aspects of his spoken teachings that appear to be unique. For example, his reference to the heart center on the right side of the chest. He said that this was the source of the ‘I’ and the place in the body where the sense of ‘I’ had to return in order for realisation to take place. People who talk about his teachings in the West rarely seem to mention this point.

David Godman: Ramana didn’t mention it much either. On a few occasions when he was asked about it, he said it was more important to have the experience of the Self, rather than locate it in some part of the body. It is true that no teacher who came before him ever mentioned this, but I would not say that this is a major aspect of his teachings. Nor would I say that it is necessary to have this knowledge in order to have an experience of the Self.

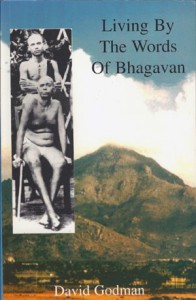

Rob Sacks: How did you choose the subjects for your three biographical books?

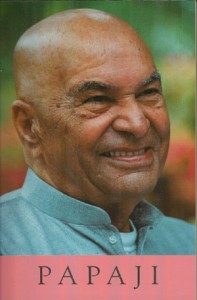

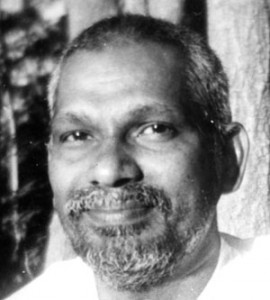

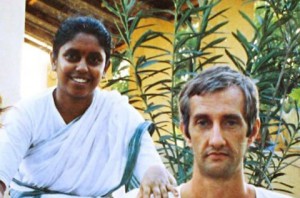

David Godman: In two of the three cases the subjects chose me. When I went to Lakshmana Swamy’s ashram in the early 1980s, he asked me to write a brief biography of Saradamma, a project that eventually turned into a book-length account of both of them. A few years later, when I wrote a fifty-page account of Papaji’s experiences with Ramana, intending to use it in a book about Ramana’s disciples, Papaji liked it so much, he invited me back to Lucknow to do a complete biography on him. As for the third biography, I approached Annamalai Swami in the late 1980s, hoping to interview him in order to get enough material for a chapter in the same book that was going to feature Papaji’s account. His story turned out to be so engrossing, so detailed, so unlike anything I had come across in the existing Ramana literature, it soon expanded into a book-length project.

Rob Sacks: All these people seem to be Self-realised. Did you pick them for this reason? How did you know that they are Self-realised?

David Godman: The simple answer is that no one who is not a jnani can really tell who is in that state, and I would not claim to be in that state myself. Ramana told people that the peace one feels in the presence of such beings is a good indication that one is in the presence of an enlightened being, but this is a sign not a proof.

When I first went to see Lakshmana Swamy in the late 1970s, I did not go there with any intention of evaluating him. But as soon as I looked into his eyes, something inside me said, ‘This man is a jnani‘. Nothing has ever caused me to doubt that first impression. I don’t know how I came to that conclusion because I had never had that kind of thought before with anybody else. Something inside me just knew. Up till the time I first met him, I had been meditating intensively for most of the day for a period of about eighteen months. My mind was fairly quiet most of the time and I really felt that I was making good progress on the road to Self-realisation. However, within a few seconds of being looked at by Lakshmana Swamy, I was in a state of stillness and peace that was way beyond anything that I had experienced through my own efforts. That one darshan effectively demonstrated to me the need for a human Guru, and it also demonstrated to me that there were still people alive in the Ramana lineage who seemed to have the same power and presence that I had read about in so many Ramanasramam books. Since that day a large portion of my life and energy has been devoted to serving such beings and writing about their life and teachings.

Rob Sacks: What is Self-realisation? The terms ‘glimpse’ and ‘waking-up experience’ appear in Nothing Ever Happened. Did you invent these terms? What is the relationship between a glimpse or waking-up experience and Self-realisation?

David Godman: I would say that Self-realisation is what remains when the mind irrevocably dies in the Heart. The Heart is not a particular place in the body. It is the formless Self, the source and origin of all manifestation. Self-realisation is permanent and irreversible. I also suspect that it is quite rare. Many people have had glimpses or temporary experiences of a state of being in which the mind, the individual ‘I’, temporarily stops functioning, but I don’t think that there are many people in the world in whom the ‘I’ has died.

Papaji used to say, ‘What comes and goes is not real. If you have had an experience that came and went, it was not an experience of the Self because the Self never comes and goes.’

I think this is an interesting comment. If it is true, it means that most waking-up experiences are merely new states of mind. It is only when the mind dies completely, never to rise again, that the Self really shines as one’s own natural state.

The terms ‘glimpses’ and ‘waking-up experiences’ that you refer to are temporary. They come and they go because the ‘I’ itself has not been permanently eradicated. A powerful Guru may be able to give a glimpse of the Self to just about anyone, but it is not within his power to make it stick. If the person has a mind that is full of desires, those desires will eventually rise again and cover up the glimpse.

Rob Sacks: Do Westerners tend to have an exaggerated idea of the significance of these preliminary experiences?

David Godman: When these temporary no-mind states are being experienced, their importance can be greatly exaggerated by people who think that they have attained permanent enlightenment. But in most cases the feeling of self-importance vanishes along with the experience.

Rob Sacks: I think you quote Papaji as saying that he met only two Self-realised people in his entire life, Sri Ramana and a Spanish priest. But he also met Nisargadatta Maharaj. Does this mean that he didn’t think Maharaj was Self-realised? Can you shed any light on this?

David Godman: When I first talked to Papaji in1992, I asked him how many jnanis he had met in his life. He scratched his head and came up with three names: Ramana Maharshi, a Sufi pir he met in Madras and Tiruvannamalai, and a wandering mahatma who lived in the forests between Tiruvannamalai and Bangalore. When I got to know him better, he would sometimes add names to the list, and Nisargadatta Maharaj was one of them. He went to see him many times in the 1970s and was very impressed with him. J. Krishnamurti also made the list, although Papaji didn’t think much of him as a teacher. The Spanish priest never appeared on his list. Papaji said he was the best Christian he had ever met, but he never said he was enlightened.

This list might expand or contract according to his mood or memory, but it never exceeded seven. These were all people he had met on his travels. What I found curious about this was that he never ever included any of his own disciples on this master list, an omission that might lead one to infer that none of his disciples had actually attained the final sahaja or natural state of the jnani. This is both interesting and paradoxical since many of his disciples were told very categorically by him, ‘You are enlightened. You are free.’ When I wrote his biography, I recovered several thousand letters Papaji had written to devotees all over the world. I would say that at least fifty of them could produce a hand-written letter from Papaji congratulating them on their enlightenment.

In the vast majority of cases these experiences were temporary. I often wondered why Papaji was so enthusiastic about these temporary experiences, and many other people felt the same way. Lots of people asked him about this, but I don’t know anyone who got a straight answer, including me. When I asked him about this phenomenon, he said that he lived in the silence and that when silence spoke, it always said the most appropriate thing, even though it might not be factually accurate. He added, ‘I have spent all my life in that silence. I have learned to trust what it says.’

Implicit in this statement is a recognition that Papaji is sometimes telling people that they are enlightened when he can see clearly that they are not. He trusted the source of these statements, but he could never give a good explanation of why the silence was making him say these things.

Rob Sacks: Here’s a question from a reader which I pass along to you: “Papaji says that the only thing that needs to be done is to stop all effort. When this happens, there is quiet and a sense of egolessness. But in that state, it is possible to ask ‘Who am I?’ and find an observer whose source is yet to be found. In other words, in that state, it seems that self-enquiry is still needed. Does this mean that Papaji is teaching something different from Ramana Maharshi? What is the connection between this effortless state and the state of abiding in the heart?”

David Godman: When Papaji said in satsang, ‘Make no effort,’ he was trying to put the person in front of him into a state of no-mind in which no effort is necessary or possible, since the ‘I’ has temporarily gone. He was not trying to put the person in a halfway stage in which further effort is needed.

Here is a paradox for you. Ramana Maharshi realised the Self without any effort, without being interested in it, and without any practice, and then spent the rest of his life telling people that they must make continuous effort up till the moment of enlightenment. Papaji spent a quarter of a century doing japa and meditation prior to his climactic meetings with Ramana, but when he began teaching, he always insisted that no effort was necessary to realise the Self.

Papaji’s attitude to self-enquiry was, ‘Do it once and do it properly’. Ramana’s was, ‘Do it intensively and continuously until realisation dawns’. Although you could never get Papaji to admit that there were differences between his teachings and those of his Guru, they clearly didn’t agree on the question of effort.

With regard to the question of the difference between the effortless state and the state of abiding in the Heart, I would refer to Lakshmana Swamy. He agrees with Ramana that hard, continuous effort is needed up till the moment of realisation. He also says that by effort the mind can reach the effortless thought-free state, but no further. If that state has been achieved, and if one has the good fortune to be with a realised Guru, then the power of the Self will pull the mind into the Heart and destroy it. In the effortless state, mind is still there, but when one abides in the Heart it is gone.

Papaji conceded that meditation and effort had a limited use. He would sometimes say that intense meditation would earn the punyas or spiritual merit necessary to have the opportunity to sit with a realised being. Once that has happened, effort is no longer necessary. In fact, it is counter-productive. When one meets the Guru, the power of the Self that is present in an enlightened being’s satsang takes over and gives the results and experiences that the mind is ready for.

All this probably appears to be confusing and contradictory. The teachers I have written about disagree profoundly on the question of effort and its role in Self-realisation, but they all agree that being in the presence of a realised being is the greatest aid to enlightenment. I can say from my own experience that when one is in the presence of such beings, mind drops away of its own accord.

Rob Sacks: In his book Relaxing Into Clear Seeing, Arjuna Nick Ardagh says, ‘In the past few years, there has been a dramatic increase in the ease with which Self-realisation can occur. Indeed, a kind of epidemic has begun in the West whereby the awakened view is becoming increasingly available.’ It seems to me that Arjuna is referring here to glimpses, not Self-realisation, and I wonder if they are any more common today than they have been in India for millennia. Perhaps the real difference is that Indians didn’t regard these glimpses as particularly unusual or worth noting.

David Godman: I don’t think that there is an epidemic of Self-realisation in the West or anywhere else. I think full realisation is a rare phenomenon. There are certainly more people who think that they have realised the Self, but I think that they are deluding themselves.

Rob Sacks: According to some Western advaita teachers who claim to follow Sri Ramana’s teachings, Self-realisation is a two-part process. First, there is an awakening, a temporary experience of non-duality and egolessness. The second step is to stabilise the experience of this awakening, or in other words, make it permanent. But when I read about Mathru Sri Sarada in your book No Mind — I Am the Self, I seem to get a completely different picture. In her case, a permanent awakening experience may have been necessary, but by itself was not sufficient. For her, Self-realisation happened only when her mind descended into her Heart center and dissolved permanently. I get the impression that she could have remained in the ‘awakened state’ indefinitely without this descent into the Heart. Would you comment on this?

David Godman: When egolessness is there, there is no one left who can stabilise or lose the experience. These experiences come and go. They go because the vasanas of the mind reassert themselves. When they arise and take over, you resume the practice again. This is the classic prescription of the Gita, and it is also what Ramana taught. Stay awake, stay mindful, and whenever you catch the mind straying, take it back to its source.

As regards Mathru Sri Sarada, I think you are referring to the experience she had just before she realised the Self. She felt that her mind had died because she was temporarily abiding in the Heart, but her Guru, Lakshmana Swamy, could see that her ‘I’ was not dead, which meant that this was a temporary experience. She was talking about her experiences and genuinely felt that her ‘I’ was dead, but it was not a real, permanent awakening.

A few minutes later, with the help of her Guru, the ‘I’ went back to its source and died forever. There was no fully awakened state prior to this experience. The final death of the ‘I’ in the Heart was necessary to complete the realisation process

Rob Sacks: Can you name any people who are teaching today who are Self-realised?

David Godman: I could hide behind my earlier statement and say that I am not qualified to say who is enlightened and who is not. That is true, but I have absolute faith that Lakshmana Swamy and Saradamma are in that state. I don’t want to make comments about anybody else.

Rob Sacks: What plans do you have for future books and other works?

David Godman: I am working on a third volume of The Power of the Presence, and I hope to see it published in a few months. After that, I have a project to translate and publish some of Muruganar’s poetry from Tamil into English. He recorded many of Bhagavan’s teaching statements in short Tamil verses, and most of them have never been translated. This will be a major undertaking that may take a year or two. I also hope to get back to working on Papaji in the near future. I particularly want to edit the Lucknow satsang dialogues from the early 1990s. That’s a big job, though, and would probably take years. I recently volunteered to make a book of all Sadhu Natanananda’s writings on Bhagavan for Ramanasramam. I will fit that in between all my other projects.

When I sit down in front of my screen in the morning I often have no idea what I will be working on ten minutes later. I might look at something I have edited recently, move on to something else, and then find another chapter of another book that suddenly grabs my attention and interest. Or I might switch the machine off and go outside and do some gardening instead.

I have come to the conclusion that Bhagavan brought me to Tiruvannamalai to write about him and his disciples. I have learned this the hard way. I went back to England twenty years ago, hoping to earn enough money to come back to India and not do any work here. Nobody was willing to hire me to do anything. I even flunked an interview for picking up litter in the London zoo. But as soon as I had the idea of writing a book about Bhagavan, everything fell into place. Though I had never written anything in my life, I was given a contract by a major publisher and sent back to India to write about him. That’s how Be As You Are came into existence.

A few years before that I gave up editing the Ramanasramam magazine and went to Andhra Pradesh to be with Lakshmana Swamy. My intention was just to meditate there. I had had enough of writing, but within a few weeks of my arrival he asked me to write No Mind — I am the Self. Whenever I do work on Bhagavan or his disciples, everything goes well. Whenever I try to do something else, so many problems come up, nothing ever gets accomplished or completed.

Having learned this from experience, I have now surrendered to this destiny. I enjoy the work, and many, many people seem to appreciate the books. I asked Papaji years ago whether writing all these books on Bhagavan was a distraction for the mind.

He replied, ‘Any association with Bhagavan is a blessing’. I took that as an instruction to carry on with the work.

Rob Sacks: Thanks very much for this interview, David. I learned a lot from it, and you have been extraordinarily generous.

David Godman: You’re welcome.