When I lived in Lucknow there was a woman there called Almira who had come from Hawaii to be with Papaji. She had come for a few weeks, wanted to stay longer, but had a plane ticket that had to be used within a particular time.

When she told Papaji about this, he just said, ‘Your ticket has expired’.

‘No,’ she said, ‘it’s still valid. I can show you.’

He refused to look at it when she produced it. When she attempted to get him to read the date, he waved it away. He just repeated his earlier pronouncement: ‘Your ticket has expired.’

Eventually, Almira took the decision that she was going to let her ticket run out and stay on in Lucknow.

When she told Papaji of her decision, he said, ‘See, I told you. Your ticket has expired.’

The expiry had nothing to do with the calendar. Papaji just knew that she was destined to remain in Lucknow. She stayed more than five years and didn’t leave until after Papaji had passed away.

I didn’t have a ticket printed on a piece of paper, but I did have a similar fixed idea that I would have to leave within a few weeks of my arrival. I had put aside enough money to get back to the UK and assumed I would have to buy a ticket to return there once I had no more money to support myself in Tiruvannamalai. That moment in the samadhi hall dissolved a self-imposed layer of mental agitation: that I would have to leave when I didn’t want to, and that my time at Arunachala was limited.

I think all of us waste a lot of time and energy agonising over choices and decisions in our lives because we think we are in charge of what happens to us, and we further believe we have to plan and scheme to change the circumstances in our lives, or keep them the way they are.

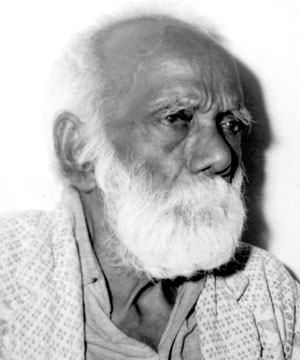

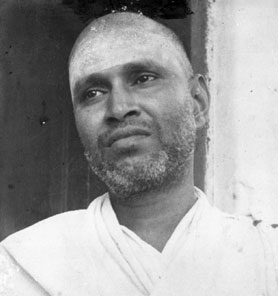

Ramaswami Pillai once asked Bhagavan, ‘Life is full of apparent choices. We waste a lot of energy thinking about what we should do. When a choice presents itself, how can we tell if it is something that we have to do, or whether it is something that will waste our time and lead us in the wrong direction.’

Before I give Bhagavan’s reply I should say that in Tamil Nadu destiny is often conceived as a load that one carries on one’s head.

Bhagavan told him, ‘Throw it down three times. If it jumps back three times, then it is something you have to do.’

If we have a mind, we can’t tell what things are destined for us. A jnani might see and know, and he might even tell us if we are lucky. The rest of us just stumble along, making plans and thinking we are in charge of future events.

I was destined to be in Tiruvannamalai. Hindsight alone tells me that. I ‘threw it off my head’ a few times, but it always jumped back. On several occasions I made attempts to be somewhere else, but they never worked out for long. Sooner or later I would always find myself back at the foot of Arunachala.

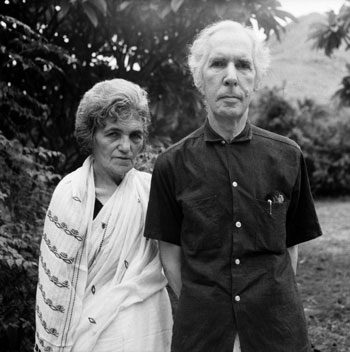

Question: You mentioned somewhere else that, while still in England and before your first visit to Sri Ramanasramam, your acquaintance with the teachings of Ramana Maharshi was through Arthur Osborne’s book, The Teachings of Ramana Maharshi in his Own Words. And surprise! You have just arrived in Tiruvannamalai and after the three days you were allowed to stay at the ashram as a newcomer, you spent the next eighteen months in Arthur Osborne’s home, although he himself had passed away a few years before. You have been writing on Sri Ramana’s life, teachings and his devotees ever since. To an external observer, regarding the work that both of you have been engaged in, your destiny appears to both parallel Osborne’s and be a continuation of it. I marvel at the coincidence. It is as if choosing that room in Lucia Osborne’s house out of several other possibilities, you actually chose to continue Arthur Osborne’s work. Could you tell us more about that period in your life? It would be interesting to know more about Lucia Osborne too.

Answer: First of all, I didn’t ‘choose’ to stay in the Osborne house. As I said earlier, Raja Iyer took me to see a few people who lived near the ashram, one of whom was Lucia Osborne. She then showed me around the neighbourhood and pointed out the places that were available for rent. We could not contact the owners of some of the various rooms we saw on this brief tour, but Mrs Osborne promised to do it for me. In those days there were very few places to stay; maybe four or five options that collectively contained about ten rentable rooms. It didn’t matter much then because there were rarely more than ten people who wanted to rent a room in the vicinity of the ashram. I think there were probably five or six foreigners staying near the ashram when I arrived. Over the next year or so the numbers didn’t increase that much, even in winter, which is when most people come.

At the end of the tour Mrs Osborne just said, ‘Bring your bag here on the day you leave the ashram and I will show you which room I have taken for you.’

I showed up after lunch on the day I had to leave the ashram. We sat talking for about an hour on her veranda, with me wondering when we were going to get round to the business of being shown where I was going to sleep that night. Eventually, she said ‘Come with me’ and took me to a room at the back of her house that I had never seen before.

‘You can stay here,’ she said. ‘It’s Rs 30 a month.’

I accepted and moved in immediately. In retrospect I think the hour of conversation was some kind of interview, which I eventually passed. If I had failed it, I would probably have been taken to one of the other places I had been shown on my first visit. So, I think it would be more accurate to say that she chose me, rather than the other way round.

You said, ‘It is as if choosing that room in Lucia Osborne’s house out of several other possibilities, you actually chose to continue Arthur Osborne’s work’.

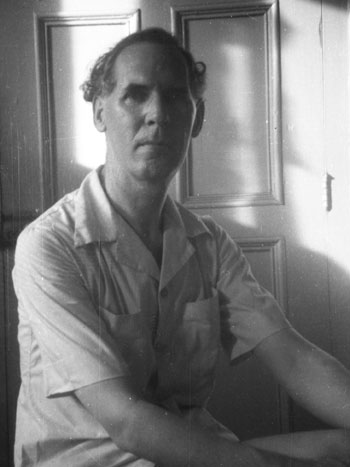

I just explained that I didn’t choose to stay in the Osborne house. I think it is also true that I didn’t choose to continue Osborne’s literary work on Bhagavan. In the eighteen months I stayed in that house, I didn’t write anything except the occasional letter. Most evenings I could hear Lucia Osborne banging away on her old manual typewriter, trying to finish the autobiography that Arthur had started, a work which was far from completion when he passed away in 1970. However, it didn’t inspire me to do any writing myself. In fact, I remember telling Mrs Osborne one day that everyone who came to Ramanasramam seemed to think that he or she had to write a book about what happened while he or she was here. I think I found it a bit amusing at the time that so many people were inspired to write down their experiences. I had, of course, read all the offerings by old devotees that were in print at that time, but at no point did I ever think that I had something of my own to contribute.

I didn’t begin to write until at least a year after I left that house. I had volunteered to look after the ashram library. Many of the newer books had been donated to the ashram by publishers who wanted their books to be reviewed in The Mountain Path. I began looking after the book review section of the magazine, and doing the occasional review myself, simply to ensure that there would be a good supply of books coming to the ashram.

Around 1979 Prof. K. Swaminathan, who was then just a member of the editorial board of The Mountain Path, came to the ashram for a visit. He had the beginnings of a cataract and found reading hard work. He asked me to read out some of the material that had been submitted. When I read out a review I had written – quite a short one, maybe only two paragraphs – he praised it effusively. Then he disappeared into the ashram office and came out five minutes later to say that I was now a member of the editorial board myself. Even then it didn’t occur to me that I should write anything original.

About a year later Nisargadatta Maharaj asked me what I did at Ramanasramam. When I included ‘book reviews’ on the list of my activities, he glared at me and said, very strongly, ‘Why don’t you write about the teachings? Writing about the teachings is very important.’

I remember being very surprised, firstly, because it was unusual for him to tell people to write, and secondly because it had never occurred to me that I had anything to say about his or Bhagavan’s teachings. I suppose, in retrospect, he saw that I had some sort of destiny in this field, and by making this strong recommendation, he probably felt that he was giving me a push in the right direction.

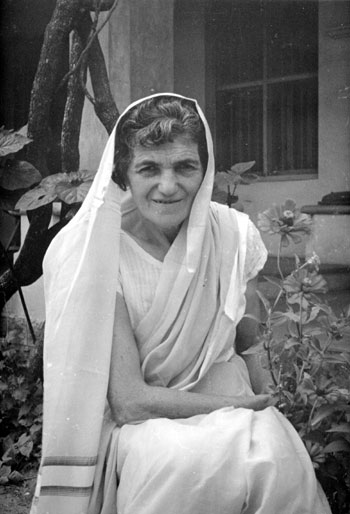

Now, going back to your suggestion that I share a few memories of Lucia Osborne, I have to say that I learned very little about her in the eighteen months that I stayed in her house. It is not because she was reticent or unwilling to talk: it was simply that in those days I had very little interest in the personal stories and histories of devotees I met. There were so many people around in those days that I could have talked to and gained useful information from, but the thought of asking them to tell me about their time with Bhagavan simply never occurred to me. Sadhu Natanananda, for example, lived about 50 metres from me while I was staying in the Osborne house, but I never once spoke to him. We would pass each other on the street on the way to our respective rooms, occasionally nod an unspoken greeting to each other, and then go our separate ways. I only heard him speak for the first time about two weeks ago when I saw an old French documentary about India, made in the 60s by Louis Malle, that featured a few minutes about Ramanasramam. Sadhu Natanananda appeared it, talking briefly about Bhagavan’s teachings.

When I moved into Ramanasramam in the late 70s, I ended up in the room next to S. S. Cohen. The same thing happened there as well. I would greet him once in a while, and occasionally ask about his health since he was old and frail, but I never once asked him to talk about his time with Bhagavan.

When I first arrived in the ashram in 1976, I had asked him where he was from.

He laughed and said, ‘The last time I was there it was called “Turkish Mesopotamia”,’ from which I deduced that he had been living in Iraq prior to the First World War in a part of the region that was administered by the old Ottoman Empire. That was the extent of my personal enquiries.

I am beginning to regret my complete absence of curiosity in my early years at the ashram. Let me give you an example of why it is now bothering me. I have begun to research Maurice Frydman’s life and hope to write a book on him, if I collect sufficient material. He was a Polish-Jewish devotee, and so was Lucia Osborne. He visited the Osbornes many times and doubtless shared many stories about Bhagavan and life in Poland in the twenties and thirties. It never occurred to me to ask about him. S. S. Cohen, another Jew, also knew Maurice well. When he lived in Vellore, a town about 80 km north of Tiruvannamalai, Cohen was the local guardian of Maurice’s adopted daughter Maggie, who was then studying in the CMC Medical College there. I am sure he could have given me a vast amount of information on Maurice had I bothered to raise the subject. Then there was a Bangalore devotee of Bhagavan called K. Ramaswami. He was one of Maurice’s oldest friends and was present when he passed away in Mumbai in 1976. In the 1930s he worked in the electrical factory that Maurice managed on behalf of the Maharaja of Mysore. I knew Ramaswami well, and even visited him a few times in his house in Bangalore. But, as with all the other people I have mentioned, it never occurred to me to ask for stories or information about Maurice.

In recent months I have been casting my net in all directions, looking for people who had some personal connection with Maurice. I have managed to locate a few elderly people, some of whom are in their nineties. My job would have been a lot easier had I taken the opportunities that were available to me in the 1970s and early 80s.

The only story I remember hearing about Frydman from the old devotees who were present in the ashram in the 1970s came from Viswanatha Swami, someone else I now wish I had spent more time with and talked to more. He casually mentioned once that Frydman was a bit of a practical joker who once sat up in the branches of the iluppai tree that is near the ashram gate and dropped things on the heads of devotees who were passing underneath. It’s not much of a story haul, given the wealth of material that must have been in the memories of the people who were there at the time.

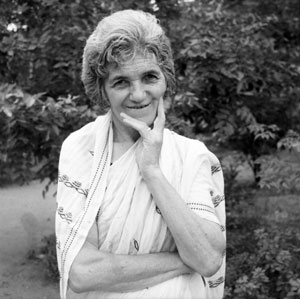

Since you asked about Lucia Osborne, there is one story that has always stuck in my mind. When she decided to marry Arthur, a non-Jew, her father was so angry, he organised a procession in his local neighbourhood in which all the members of the family were compelled to attend. He marched at the head, with all his family in tow, holding a big placard that read, ‘Lucia is no longer my daughter. From now on, no one will mention her name.’

Her marriage to Arthur saved Lucia from the Holocaust. At the end of the Second World War, when Lucia was safe at Ramanasramam and waiting for Arthur to come from his internment in Thailand, only one of the people who had gone on that procession was still alive.

Lucia didn’t talk much about her past. This particular story was told to me by Buday, a Polish neighbour of hers who was a regular visitor. I didn’t get much information from her myself. I could tell you about her dietary peculiarities, that she told me she had had thirty cats in thirty-three years in India, that she had lead poisoning from using too much lead-based paint during her years as an artist, that she was an amateur homoeopath, and so on. I could tell you lots of trivial, mundane things that I picked up from sharing a house with her. What I can’t tell you is stories about herself and Bhagavan, and I can’t do that because, somehow, I never bothered to ask.

Question: Could you build a picture of Sri Ramanasramam of those days? There must have been some devotees who continued living there after Sri Ramana’s mahasamadhi and who knew him well. Some of them are quite well known since their stories have been recorded. Do you have anything of your own to add? Was there anyone among them who you were especially close to? Was life at the ashram in those days in any way different to what it is today?