I like publishing my own stuff because I can choose any topic that appeals to me; I can write as much or as little as I like, and I have no deadlines. Having said that, though, I must add that I only publish material on Ramana Maharshi, his teachings, his disciples, and his Guru, Arunachala. I have no interest in branching out into other fields.

Selling and distribution can occasionally be a bit of a headache, particularly since potential customers are spread thinly all over the world. Having been in the spiritual book business for almost twenty years, I think I would be right in saying that it is much harder to distribute a good spiritual book nowadays than it was in the late eighties and early nineties. Spiritual bookstores are chronically short of money to pay their bills, and mainstream bookstores are primarily interested in bestsellers. Amazon, along with Barnes and Noble, are putting a lot of good outlets out of business.

My advertising budget is zero. I don’t do book tours. I don’t sit in shops and sign books. I don’t go from city to city doing radio interviews. These are the standard promotional tools in the West. Many publishers nowadays won’t even consider giving an author a contract unless she is willing to go on the road and promote the book for them. I have brought out three new books in the last eighteen months, and during that period there hasn’t been a single night when I haven’t slept in my own bed in Tiruvannamalai. I have a good mailing list of people who I know are interested in my books. Whenever I have something new to offer, I notify everyone by email. Other people hear about my books from friends or from notifications on the web. Nowadays, there are so many specialised web sites, if a new book comes out on Sri Ramana, news of it will appear on sites specialising in advaita, gurus, enlightenment or Ramana Maharshi within a matter of days.

Hardly anyone comes across my books in bookstores nowadays because so few bookstores stock them. That doesn’t bother me at all. There are several thousand people in the world who appreciate Ramana Maharshi enough to buy a new book about him or his teachings. Sooner or later my books will come to the attention of these people and they will buy them. I don’t work very hard to find customers. I have a feeling that if someone is ready to appreciate a book on Sri Ramana, that book will somehow drop into his or her lap at the right time. I don’t think it’s my responsibility to try to foist my books on reluctant customers. When I was ready for Sri Ramana’s words, the book was there, waiting for me. The same thing will happen when other people need to read about him or his teachings.

Last year a man I have never met volunteered to make a web page for me that would contain details of where to buy my books. ‘OK,’ I said. ‘Thank you.’ He bought my domain name, made a simple site for me and paid the fees for two years. This year someone else I barely know offered to put in a lot of time upgrading it and adding lots of new material. ‘OK,’ I said again. ‘Thank you.’ People turn up when they are needed and the work gets done.

If any businessmen or women are reading this, they are probably scratching their heads in disbelief. However, it works. My books eventually find their customers, and from the feedback I get, the customers are generally happy with what they buy and read.

Maalok: Among the dozen or so books you have written and edited, are there any one or two that standout as being special for you personally?

David: Not really, I enjoyed working on them all. However, I think I got the most pleasure and happiness out of the biographies because they involved a lot of personal contact with all the subjects. Also, I enjoyed the research aspect of these books: tracking down little-known facts and incidents is something I always enjoy doing. Finally, once the research is over, there is the creative challenge of putting it all together into a seamless whole, constructing a narrative that enables the reader to enter into and be immersed in an astonishingly different world. I try to be as factual as possible when I do this, but at the same time I want to convey the reverence, the awe and the esteem I feel for these people. I write about these people because for me they are magnificent examples of how human lives should be lived.

Maalok: How did you gather the material for the biographies you have written? Did you use tape recorders etc. while conversing with the subjects? The reason I am asking is that on reading I am impressed by the degree of details in each one of them, which becomes especially astounding since several of them were written in the twilight years of the subjects.

David: I don’t think I had a tape recorder when I interviewed Saradamma and Lakshmana Swamy. I suppose I ought to remember something like that, but I can’t. I think I just took notes as they talked. I remember sitting with them every morning for about an hour, probably over a period of about a month. There was a lot of detail in that book simply because Saradamma had such a good memory. She had an astonishing recall. Lakshmana Swamy didn’t have such a good memory about the years that Saradamma was doing her sadhana, but her astounding photographic memory of that period more than made up for this. Lakshmana Swamy did, though, have excellent memories of his early life, his time with Sri Ramana and the years he spent as a solitary recluse. The two accounts complemented each other very well. There was no question of old age being a factor here because Lakshmana Swamy was still in his fifties then, and Saradamma was in her early twenties. She was describing events that had mostly happened five to eight years before.

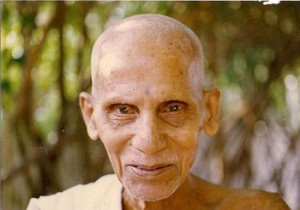

With Annamalai Swami I had taped sessions every afternoon. I would fill most of a ninety-minute tape almost every day. I would transcribe it overnight, go back the next afternoon and use the same tape again for the next day’s stories. I think it was an economy measure because I didn’t have much money at the time, but looking back on it, I wish now that I had used separate tapes and kept them all. It would have been a nice record. I am sure there are now many people who would enjoy listening to him tell his stories. He was a good story-teller, and he had a captivating narrative style. He wasn’t very good on dates or sequences of events – which story came before or after which other one – so I had to work all that out for myself later. That was an absorbing and fulfilling challenge: recreating his world, and populating it with all the characters and incidents he had told me about. I did a lot of Sherlock Holmes work, poring over old photos of ashram buildings, and going through old ashram account books, trying to match the stories he was telling me with the physical evidence of the buildings he was working on.

What I particularly liked about him was the way he would distinguish between stories that he had first-hand knowledge of and those that he didn’t. If he had been present at some incident, he would tell me. If he had heard a story second-hand, he would qualify his account by saying that he only had indirect knowledge. He wasn’t a scholarly man, but he understood the necessity of good scholarship. We were writing about his Guru, and to him the words and actions of his Guru were sacred. He wanted utmost accuracy wherever possible. Sometimes he would even give me what politicians would call ‘off-the-record briefings’. He would give me opinions on why he thought certain people behaved the way they did, but then he would add, ‘Don’t print this because this is just my opinion. I am just telling you this to give you some background information on what the ashram was like at this time.’ It was a pleasure to deal with someone who knew how to evaluate source material in this way.

When you talk to eighty-year-olds about their youth, there is always the possibility that they are misremembering things, but just about everything that was checkable from other sources turned out to be true. That gave me the confidence to believe in the reliability and accuracy of his whole narrative.

As I said, dates were not his strong point. Initially, for example, he was quite insistent that he came to Sri Ramana in 1930, but when I proved to him that Seshadri Swami died in early 1929, he had to change his mind because he had met Seshadri Swami on a few occasions. However, mistakes such as these were few and far between.

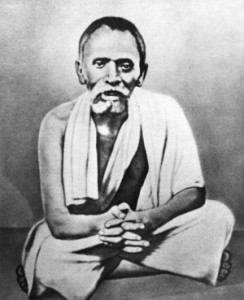

Papaji was also in his eighties when I collected the details of his life. He wrote out about 200 pages of answers for me in response to a massive biographical questionnaire I inflicted on him. It was sixteen pages long. All his satsangs were being recorded in those days, and during the hour or so he spent with visitors every day he often mentioned incidents from his early life. So, although I wasn’t recording his stories directly, I had access to a whole archive of tapes that had records of him telling stories about various things that had happened to him over the years.

I contacted many people who had known him and moved with him at various periods of his life. Their information corroborated a lot of what he had been telling me. For example, when he was a child he said that Krishna would come and play with him in his bedroom, but apparently no one else in the family could see him. I spoke to two of his surviving sisters and they both remembered incidents in which a very young Papaji seemed to be playing with an unseen friend on his bed or in the family home. On one of these occasions he went into trance that lasted for hours.

Usually, when he told a story in response to a question, I got the feeling that he was often getting his information from his memory of the last time he told the story, rather than from the original incident itself. I think a lot of people do this. However, sometimes, he would spontaneously remember some incident and start talking about it. When this happened, the most astonishing details would come out. I remember him talking about a Muslim pir he met in Madras. I had heard the story before, but when he started telling me on this occasion I could feel that he was actually back in Madras in the mid-1940s, walking down the street and describing all the things he was seeing. He was talking about walking past particular shops and businesses and describing the sights and scenes as if he were actually walking down that particular street. These stories were very precious for me. It was like having a video replay of the incident, unobstructed by any of the subsequent retellings. I learned not to interrupt when he got into this kind of mood. If you asked a question, perhaps a clarification or an explanation, the look in his eyes would change and he would not be in the street any more. He would be back in his memory, telling the story in the way he usually did.

Overall, with all the people I have written about, I satisfied myself that I was dealing with reliable memories. With Papaji and Annamalai Swami, there were occasional discrepancies that no amount of research or questioning could sort out. The events they pertained to were simply too long ago. However, I am satisfied that, to the best of my ability, I have given reliable accounts of truly great people.

Maalok: You mentioned that Papaji’s surviving sisters saw him playing with Krishna when he was young, but no one saw actually Krishna except for Papaji himself. A sceptic could say that Papaji may well have been making all this up and just telling people that he had seen Krishna. Later, when he became famous, the family would probably say, ‘Yes, yes, we saw him playing with Krishna when he was young’. Did you consider possibilities such as these?

David: Yes, this is a valid point, and I probably picked a bad example when I mentioned this particular story. Of course, no one can corroborate visionary experiences because they are almost always restricted to one person. Papaji had visions on a regular basis throughout his life, and virtually no one else ever saw them. Many of his devotees had visions of their own when they were in Papaji’s presence, and these too were only seen by one person. Even Papaji did not see them.

Leela, one of the sisters who said she had seen Papaji playing with Krishna as a boy, had a vision of Sita in Valmiki Ashram on the banks of the Ganga. Papaji was present on that occasion, and both of them saw the deity take a physical form and speak to them. Leela became somewhat hysterical and passed out. It definitely was not a normal experience for her. So, when she said that she had seen Papaji playing with Krishna when he was young, she had every reason to believe that he was telling the truth.

Many of the other stories that Papaji narrated were much easier to corroborate. Papaji had a huge fund of improbable stories and events. Some of them were so ridiculous, they left you thinking, ‘This can’t possibly be true. He’s playing a joke on us and making all this up.’ However, whenever I found people who had been present when the incident had taken place, they would always back up Papaji’s version of events, or at least tell a story that was very similar to it.

Maalok: You have mentioned that final Self-realisation is when the mind actually ‘dies’ irreversibly in the Self. You have also mentioned how Papaji used to sometimes give an account of his life based on memory of his earlier narration. The idea of memories and a dead mind seem contradictory. Could you please clarify this?

David: Many people are puzzled by this apparent conundrum. A dead mind is one in which there is no thinker of thoughts, no perceiver of perceptions, no rememberer of memories. The thoughts, the perceptions and the memories can still be there, but there is no one who believes, ‘I am remembering this incident,’ and so on. These thoughts and memories can exist quite happily in the Self, but what is completely absent is the idea that there is a person who experiences or owns them.

Papaji once gave a nice analogy: ‘You are sitting by the side of the road and cars are speeding past you in both directions. These are like the thoughts, memories and desires in your head. They are nothing to do with you, but you insist on attaching yourself to them. You grab the bumper of a passing car and get dragged along by it until you are forced to let go. This in itself is a stupid thing to do, but you don’t even learn from your mistake. You then proceed to grab hold of the bumper of the next car that comes your way. This is how you all live your lives: attaching yourself to things that are none of your business and suffering unnecessarily as a result. Don’t attach yourself to a single thought, perception or idea and you will be happy.’

In a dead mind the ‘traffic’ of mental activity may still be there, usually at a more subdued level, but there is no one who can grab hold of the bumper of an idea or a perception. This is the difference between a quiet mind and no mind at all. When the mind is still and quiet, the person who might attach himself or herself to the bumper of a new idea is still there, but when there is no mind at all, when the mind is dead, the idea that there is a person who might identify with an object of thought has been permanently eradicated. That is why it is called ‘dead mind’ or ‘destroyed mind’ in the Ramana literature. It is a state in which the possibility of identification with thoughts or ideas has definitively ended.

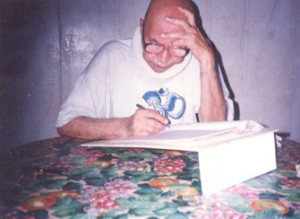

Let me go back to Papaji and what I said about his memories. Papaji said in an interview he gave in 1990 to two American dentists, ‘When I speak, I never consult my memory or my past experience’. When I asked him about this, he said that people with minds always go back to the past in order to formulate their next sentence, whereas the words of enlightened people are prompted by the Self in the present moment, and are not the consequence of past memories or experiences. This is the difference between using your mind to have a conversation and allowing the Self to put the necessary words into your mouth whenever it is necessary to speak. When there is no mind, words come out spontaneously, as and when they are required. If those words happen to take the form of a story from the past, one should not come to the conclusion that there is an ‘I’ who is delving into past memories and retrieving them. When we see an enlightened person do this, we assume that this – a mind retrieving information from the memory – is what is happening because this is the way our own minds work. We project the mechanism of our own minds onto the enlightened person and assume that she too must think and function in this way. We do this because we can’t conceive of any other way that thoughts and memories can be articulated. Just for fun, I once asked Papaji how he managed to do his shopping without using his memory or his past experiences. I should mention here that he was a ferocious bargain hunter when it came to buying vegetables. He always insisted on the best quality at the cheapest price.

‘How can you do this,’ I asked, ‘without a memory? To know whether you are getting a bargain, you have to know what the price was yesterday or last week, and to know whether or not a carrot is in a good condition, you need to need to have a memory and a prior experience of what a good carrot looks like.’

At first he just said, ‘What a stupid question!’ but then he laughed and more or less summarised what I have just explained: that there is no one who thinks, decides and chooses while he is out shopping. The Self does all these things automatically, but to an onlooker it appears as if there is someone inside the body making decisions based on past experience and knowledge.

I heard U. G. Krishnamurti talk about his shopping habits in very similar terms in the late 1970s.

He said, ‘I push my trolley down the aisle and watch an arm reach out, pick up a can and put it in the cart. It’s nothing to do with me. I didn’t tell the arm to move in that direction and select that particular can. It just happened by itself. When I reach the checkout counter, I have a basketful of food, none of which I have personally selected.’

Maalok: You obviously have a reverence for the people you were writing about. Didn’t that make it difficult to be objective about facts? For example, if you saw something ‘not so nice’ (at least as perceived by an average reader) about these people or their lives, there could have been a tendency to not include it in the books, given that you have a reverence towards them.

David: Let me start with Ramana Maharshi. I have been researching his life and teachings for a large part of the last twenty-five years and in all that time I have not come across a single incident that I would keep out of the public domain because it might give people a bad idea of him. His behaviour and demeanour at all times were impeccable. All the attributes we associate with saintliness were present in him: kindness, gentleness, humility, equanimity, tolerance, and so on. For decades he lived his life fully in the public spotlight. He had no private room of his own, so everything he did and said was open to scrutiny. Except when he went to the bathroom, he was never behind a closed door. Up until the 1940s, if you wanted to come and see him at 2 a.m. in the morning, you could walk into the hall where he lived and sit with him. Some people did occasionally invent stories about him to try to discredit him, but no one who had moved with him closely would ever believe them. There was simply no scope for scandal or misbehaviour because his life was so public, and so saintly. He never dealt with money, never spoke badly of anyone, he owned nothing except his walking stick and his water pot, and he was never alone with a woman. Only people who had never watched him live his life could invent scandalous stories about him and expect other people to believe them.