When outsiders did make up stories about him, Sri Ramana would react with amusement rather than annoyance. When a disgruntled ex-devotee brought out an extremely libellous pamphlet about him in the early 1930s, the ashram manager wanted to go to court and sue the author to protect the good name of Sri Ramana and the ashram.

Sri Ramana dissuaded him and said, ‘Why don’t you instead sell it at the front gate? The good devotees will read it and not believe a word of it. The bad devotees will believe it and stay away. That way we will get fewer visitors here.’

The manager, of course, could never agree to such a proposal since the devotees would not stand for such a scurrilous booklet being sold on the ashram’s premises. However, the whole incident illustrates an interesting aspect of Sri Ramana’s character: not only was he unmoved by personal criticism, he occasionally enjoyed it, and at times even seemed to revel in it. It is said in the sastras that response to praise or blame is one of the last things to go before enlightenment happens. It was definitely absent in Sri Ramana. Let me mention one other story that very few people have heard about. There used to be a scrapbook in the hall where Sri Ramana lived. If there were any stories about him in the newspapers, someone would cut them out and paste them in the book. They were either neutral reports that gave information about his life, teachings and ashram, or they were very favourable testimonials. One day a highly critical report appeared in a newspaper. Sri Ramana himself cut it out and pasted it on the front cover of the scrapbook, overruling the horrified objections of all the devotees.

‘Everyone should have their say,’ he said. ‘Why should we keep only the good reports? Why should we suppress the bad ones?’

This is all a roundabout way of saying that there are no bad stories about Sri Ramana, so the question of suppressing them doesn’t arise.

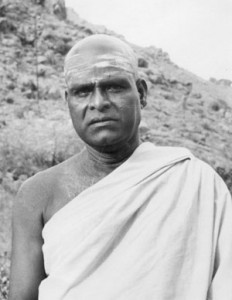

A few years ago I was sitting in on a conversation between Kunju Swami, someone who had been with Sri Ramana since the early 1920s, and a friend of mine, Michael James. Kunju Swami was revising one of his books, deleting a few stories that he thought might give a bad impression of Sri Ramana. To me the deletions were pointless. For example, when Sadhu Natanananda first came to Sri Ramana in 1918, he asked someone in the temple in town for directions.

The man he spoke to said, ‘Don’t waste your time going to see that man. I have been visiting him for sixteen years. He is completely indifferent to everyone.’

Kunju Swami wanted to delete this reply because he didn’t want people to feel that someone could spend sixteen years visiting Bhagavan and not feel some benefit. For me, this is a reflection on this particular visitor’s spiritual immaturity, not a criticism of Sri Ramana’s transforming power. The story reflects badly on the person who was unable to recognise Sri Ramana’s greatness, not on Sri Ramana himself. It may rain twenty-four hours a day, but nothing will grow in sterile soil.

Anyway, Michael asked Kunju Swami, ‘In the thirty years that you were associated with Sri Ramana [1920-50] did you ever see him do or say anything that was so bad or so embarrassing that you feel that you couldn’t tell anyone, or make it public, because it would reflect badly on his public image?’

Kunju Swami thought for a while and said ‘No’.

‘Then who are we protecting by censoring stories?’ asked Michael.

He didn’t receive an answer.

Kunju Swami felt that that it was an expression of his Guru bhakti to filter out any stories that might, even remotely, cause readers to think that Sri Ramana was not some great omnipotent being who transformed everyone who came to him. I take a different view. I don’t think I need to burnish Sri Ramana’s image at all because the uncensored truth of his life speaks for itself.

Having said all this, I should also make it clear that Sri Ramana himself readily admitted that enlightenment didn’t turn people into paragons of virtue. Like most great Masters before him, he said that it was impossible to judge whether someone was enlightened by what he or she did or said. Saintliness does not necessarily go hand in hand with enlightenment, although most people like to think that it should. Sri Ramana was a rare conjunction of saintliness and enlightenment, but many other Masters and enlightened beings were not. They were not less enlightened because they didn’t conform to the social and ethical mores of their times, they simply had different destinies to fulfil.

In Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, Sri Ramana narrates the story of Kaduveli Siddhar, an austere ascetic who attracted public ridicule by having an affair with a temple dancer. A local king offered a reward to anyone who could prove whether this man really was a saint or not. At the time the challenge was issued, Kaduveli Siddhar was subsisting on dry leaves that fell from trees. When the dancer eventually gave birth to Kaduveli Siddhar’s baby, she thought that she had proved her point and went to the king to collect her reward.

The king, who wanted some public confirmation of their intimate relationship, arranged a dance performance. When it was under way, the dancer stretched out her foot towards Kaduveli Siddhar because one of her anklets had become loose. When he retied it for her, the audience jeered at him. Kaduveli Siddhar was unmoved. He sang a Tamil verse, part of which said, ‘If it is true that I sleep day and night quite aware of the Self, may this stone burst into two and become the wide expanse’.

Immediately, a nearby stone idol split apart with a resounding crack, much to the astonishment of the audience.

Sri Ramana’s conclusion to this story was, ‘He proved himself to be an unswerving jnani. One should not be deceived by the external appearance of a jnani.’

I find it fascinating that Sri Ramana, a man of impeccable saintliness, could say that behaviour such as this could not be taken to indicate that Kaduveli Siddhar was unenlightened.

Maalok: That seems to take care of Ramana Maharshi. What about the other people you have written about?

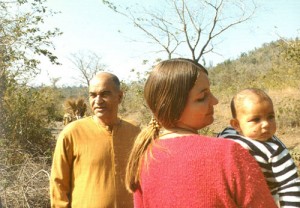

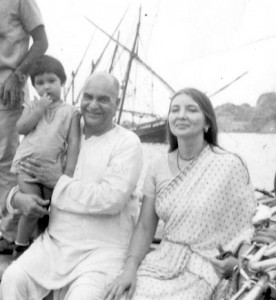

David: Well, the story of Kaduveli Siddhar reminds me of Papaji, who took a second wife, a Belgian woman called Meera, while his first wife was still alive, and even fathered a daughter, Mukti, with her. He was over sixty at the time, and Meera was not much more than twenty. This relationship upset many of Papaji’s devotees, and a significant number of them abandoned him because they all thought that he had fallen from his high state. Papaji himself did not conceal this relationship. As soon as the baby was born, he brought both Meera and Mukti to his parents’ home in Lucknow to introduce Mukti to her grandparents. When I was researching his biography, I told him that it was his decision whether or not this story went into the book. In response, he sat down and wrote out an account of the relationship for me. He didn’t think that it was anything that he needed to conceal. Though many people might think badly of him because of this relationship, there was never any question of suppressing it, of leaving it out of the book.

Maalok: Did he ever explain why he started this relationship? Did he give any reasons?

David: Papaji, and enlightened people in general, never have any reasons for the actions they undertake. Since they don’t have minds that choose and decide, they don’t generate reasons for future courses of action.

I remember when there was a plan to go on an extensive foreign tour. Tickets had been booked, visas had been obtained. When the travel agents arrived with the tickets, he simply said, ‘I’m not going anywhere,’ and the trip was cancelled. A few weeks later, when someone asked him the reason for the sudden last-minute cancellation, he said, ‘Reasons? I don’t have reasons for anything I do.’

When you abide as the Self, you do whatever the Self prompts you to do, without thinking or knowing why. There is nobody there who can say, ‘I should do this; I should not do that,’ because there is no one left who can make these decisions.

I once met someone who lived with him in Hardwar. They used to go for walks along the Ganga every day, often taking the same route. Sometimes Papaji would start off along one route and then, for no apparent reason, he would veer right or left and head off somewhere else. The following dialogue once ensued:

‘Where are we going?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Why did you turn off the path?’

‘I don’t know. Something just impelled me to walk in this direction.’

‘How far do we have to go?’

‘I don’t know. I will know when we get there.’

‘Where’s ”there”?’

‘I don’t know. When we get there I will know why I started walking this way.’

Eventually, they met a man in the forest, and that man had a waking-up experience with Papaji. The Self knew that this man was ready for such an experience and it directed Papaji towards him. Papaji didn’t know that he had been diverted towards this meeting until he met the man. He simply accepted that the Self had propelled him in a particular direction. He didn’t question or doubt the diversion. In fact, he didn’t think or worry about it in any way. He just let the Self take him to where he was needed.

I think we can say that Papaji had a destined meeting with this man. I think I would also say that Papaji had a destiny with Meera, some karma to work out with her. Because the business involved sex and a baby rather than a meeting in a forest that resulted in a waking-up experience, many people would say that he behaved immorally, but I would just say that in both cases his body fulfilled its ordained destiny.

Maalok: On reading your above explanation a vast majority of people, especially sceptics would say, ‘That’s an extraordinarily lenient view to take of a man who was fathering a baby outside marriage with a woman forty years his junior’.

David: In Sri Ramana Darsanam, a book I recently edited for Sri Ramanasramam, the author, Sadhu Natanananda, attributes the following remarks to Sri Ramakrishna, the great 19th century Bengali saint: ‘Even if my Guru is one who frequents the toddy shop, I will not superimpose any blemish on him. Why? Because I know that he is not going to lose his Guru-nature simply because of that. I have taken refuge in him not for examining and investigating his external life. That also is not my duty. Therefore, whatever happens, he alone is my Guru.’

The word Guru means ‘the one who dispels darkness’. Someone who has ‘Guru-nature’ has the ability to wake people up from the darkness of their self-inflicted ignorance and show them the light of the Self. Papaji had that Guru-nature. In the four years that I was writing and researching his biography I came across innumerable people from all over the world who testified that, in an encounter with him, they had had a direct experience of the Self. The experiences often didn’t stay, but the fact that they happened at all indicates to me that Papaji had that Guru-nature, that rare ability to show people the Self. He could be cranky and irascible at times, but no one who moved with him for any length of time could doubt that a massive, transforming energy was radiating from him.

Maalok: So would it be correct to surmise that, in your opinion, an enlightened Guru can never be held accountable for his or her actions? That we never have the right to complain about or criticise his or her behaviour simply because it does not conform to accepted canons of morality?

David: For me, the true Guru is God manifesting in a human form. There is nobody inside the Guru’s body who chooses or decides to take actions, and no one there to take responsibility for them. What they say is the word of God, and what they do are the actions of God. People who want to judge them by their words and actions are just seeing a body and are assuming that there is a mind inside it that thinks and decides in much the same way that they do. They can’t see the divinity behind the form, and they can’t feel or experience it in the radiations that come of that form.

When Saradamma was doing her sadhana at Lakshmana Swamy’s ashram in the 1970s, he occasionally treated her very harshly and put her through many tests.

Years later, after her own realisation, Saradamma told me, ‘You shouldn’t think that Swamy was sitting in his house, plotting and scheming: ”I will test Sarada in this way and see how she reacts.” The jnani has no mind to think, plan and decide like this. I was tested by the Self because I needed to be tested. Nobody planned these tests, although it looks as if Swamy did.’

When Annamalai Swami came to Ramanashram in the late 1920s, Sri Ramana made him work very hard for many years. Whenever he saw Annamalai Swami sitting down, doing nothing, he would invent some job for him to keep him busy. He set up situations in which Annamalai Swami would be brought into fierce conflict on a regular basis with the ashram manager. This went on for about twelve years, at the end of which Sri Ramana told him, ‘Your karma is finished,’ and repeated the phrase twice. From then on, Annamalai Swami was allowed to meditate in peace by himself. Who can judge something like this? The Self, acting through Sri Ramana, made Annamalai Swami toil hard for years in a confrontational situation, while other people there had a much easier life.

Sometimes the Guru has to be harsh because other methods don’t work. Nisargadatta Maharaj once said, ‘You are all holding onto the banks of a river, while I am trying to launch you out into the middle where you can float with the flow. I tell you to let go, but you don’t do it, or you ask for a method to accomplish the letting go. I ask you nicely to let go, but you don’t listen. In the end I give up and just stamp on your fingers.’

How can you judge apparently harsh behaviour when its goal is the liberation of devotees? What looks like bad behaviour to an ignorant onlooker might in fact be just what a particular devotee needs.

Papaji appeared to treat Meera and Mukti very harshly in the 1980s and early 90s. They both suffered a lot at his hands, but when I spoke to them in early 1998, just after Papaji passed away, they both conceded that the treatment had been very effective from a spiritual point of view.

Experience has taught me that Gurus rarely behave in what ordinary people would regard as a socially acceptable way. I take the position that their apparently erratic behaviour is necessary to crush devotees’ egos. I don’t judge them. I accept that are doing what the situation demands, without planning, choosing or deciding.

Maalok: We have digressed a little from the original question. Have you ever left out stories about the people you have written about because you felt that they would give a bad impression of their subjects?

David: The main censors were the subjects themselves, but in all cases the censored stories were about other people, not about themselves. Even Sri Ramana did this. When Self-Realization was first published in 1931, there was an extensive chapter about the period when Sri Ramana was living on the hill. During that period many jealous sadhus campaigned against him, trying to drive him away. From their point of view, Sri Ramana was stealing their business because he was attracting too many devotees. One sadhu tried to kill him by rolling rocks down a hill onto him. Someone else tried to poison him. When the book was first published, Sri Ramana asked that many of these stories be left out of the next edition because most of these people were still alive. He thought that they would be upset when they found out that an account of their harassment had been published. Later on, in the 1940s, when they had all passed away, he said that the stories could be put back in because there was no one left alive who could be offended.