When I wrote Lakshmana Swamy’s biography he also deleted a few stories for the same reason.

‘That particular person is still alive,’ he told me. ‘She and her husband may be upset if they find that this particular story has been published.’

In that particular book I let Lakshmana Swamy and Saradamma decide which stories they wanted to be included or excluded. None of the ones that were excluded would have reflected badly on them. On the contrary, I think that many of them would have enhanced their reputation. Some quite miraculous events were excluded, much to my regret, but don’t ask me what they are because I am abiding by their decision not to make them public.

Annamalai Swami also asked me to omit a few stories that didn’t show some of Sri Ramana’s devotees in a favourable light. Some of them were still alive, and a few were personally well known to me, so I recognised the validity of his request.

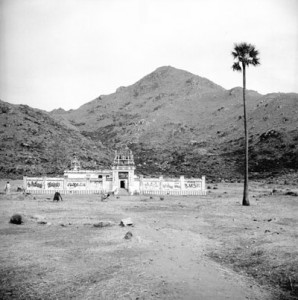

Let me tell you one story, just to give you some idea of the sort of thing that we are dealing with here. In the 1920s, quite a few of the sadhus who congregated around Sri Ramana were regular users of ganja. Sri Ramana discouraged them from this habit, but they didn’t listen to him. They used to congregate in a small Draupadi shrine about 300 yards from the ashram. These people would come to Sri Ramana and say, ‘We are going for Draupadi darshan,’ which everyone knew was the code for ‘We’re going off for a smoke’.

Ramaswami Pillai was one of this ganja-taking group. When he returned from the Draupadi Temple, he would be in a garrulous mood, and would often interrupt the question-and-answer sessions that were going on in the hall. Someone would ask Sri Ramana a question, and Ramaswami Pillai would then launch into a long, stoned advaita ramble, which he thought was the perfect answer to the question. Eventually, to circumvent these interruptions, a rule was passed that no one could interrupt a dialogue between a visitor and Sri Ramana unless they were invited to do so by either of the two parties to the conversation.

One day, a man came to the hall and began to question Sri Ramana in a very argumentative way. Sri Ramana was at first patient with him, but after a few minutes he turned to his attendant and said, ‘This man hasn’t come here to learn anything. He has only come to fight and quarrel. Go and fetch Ramaswami Pillai. He can fight and quarrel with him.’

I thought this was a very funny story, a good slice of ashram life from the 1920s, but I could also recognise the validity of not publishing it. Ramaswami Pillai was still alive at the time. In fact, he was a good friend of mine, and I often visited him. The next time I saw him, I asked him if it was true. He laughed and agreed that it was. He also confessed that once, when he was very stoned, he went on the rampage with a machete and chopped down all the ashram’s banana trees. Though he wasn’t at all embarrassed by these memories, I decided not to pass them on while he was still alive. I am telling you now because, following Sri Ramana’s policy, there is no one left alive who can be embarrassed or hurt by them.

Interestingly, it was Seshadri Swami rather than Sri Ramana who cured him of the ganja habit. Seshadri Swami just looked at him and told him off for smoking ganja. From that moment on, Ramaswami Pillai never again felt the urge to smoke.

There are many stories such as these that I chose for various reasons not to include in any of my books. None of them was excluded because they might reflect badly on the subjects of the book.

Maalok: Were there any other constraints that made you decide what to put into and what to leave out of your books?

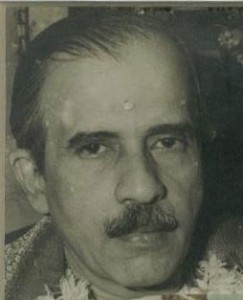

David: When I wrote Nothing Ever Happened I included many accounts that had been written by devotees themselves. I also interviewed many people who had known Papaji, and I included many of these interviews in the book. Whenever I did this, I would always show the author or the interviewee my final draft. If they wanted to make changes, they were quite free to do so. I wanted all the contributors to be satisfied that I had given a fair and accurate presentation of their views and their stories. The encounter between a Guru and a disciple is for many people a sacred one, and I didn’t want to be guilty of misrepresenting or misrecording them through ignorance or inadvertence.

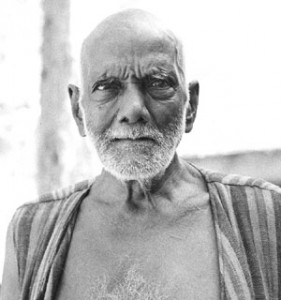

When Living by the Words of Bhagavan came out, some people from Ramanasramam came to Annamalai Swami and asked him to change or delete some of the stories in subsequent editions. He had no problem with omitting stories about other people, but he adamantly refused to change any of the accounts of the exchanges that took place between himself and Sri Ramana.

He said, ‘The words of my Guru are sacred. Everything he told me is sacred. Everything I saw him do is sacred to me. I have lived my life by following his words and his example. All these things are sacred to me, and no one has the right to change them. These are his gifts to me, and I accept them as his prasad. To change any of these things would be to refuse his prasad or to throw it away. I will never do that.’

I think all devotees think this way about the encounters they have had with their Guru, which is why I don’t want to be guilty of misrepresenting any of these meetings.

Maalok: Going back to my original question, do you ever feel that your reverence for your subjects prevents you from recording their stories in an objective way?

David: When I wrote the biographies of Lakshmana Swamy, Saradamma, Annamalai Swami and Papaji, the subjects were still alive. I worked closely with all them on their stories and always gave them the final authority to include something or to leave it out. I had enormous respect and admiration for all of them. I saw myself as a vehicle for them to get their stories out, not as someone who was sitting in judgement on them. I used my writing skills to express the sense of awe I felt when I encountered the stories of their lives and accomplishments. They were not hagiographies since I did my utmost to research and corroborate all the facts I was given, but at the same time I want to make it clear that in some sense these books were an act of worship for me, an offering to God. When I had finished writing Nothing Ever Happened I put the following verse from Tukaram in my introduction:

Words are the only

Jewels I possess.

Words are the only

Clothes I wear.

Words are the only food

That sustains my life.

Words are the only wealth

I distribute among people.Says Tuka [Tukaram],

‘Witness the Word.

He is God.

I worship Him

With words’.

This is how I feel about my writings. I worship manifestations of God on earth with the words that I string together. I don’t worship by inventing stories or by suppressing them. I use my intellect to assemble credible, authoritative and readable accounts that I hope will imbue readers with a desire for liberation and a respect for Ramana Maharshi and all the teachers and devotees in his lineage.

Maalok: There is a prevalent myth among many people who don’t know much about Ramana Maharshi that he rarely spoke. When these people see volumes and volumes of books written that claim to be ‘Talks with Ramana Maharshi’ they question the authenticity of these books. Were these talks real? How authentic are the sources?

David: Ramana Maharshi was silent for a lot of the time, but if you had a spiritual query to put to him, he would generally be happy to give you an answer, often quite a detailed one. I mentioned Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi a little earlier. Someone who picks this up might come to the conclusion that he was a talkative man because there are over 600 pages of dialogues there. But have a look at the dates. The book covers a four-year period in the late 1930s. If you average that out, it comes to about half a page a day. That’s not a lot of talking for a man who sat in public for up to eighteen hours every day.

The question of how authentic all the books about Sri Ramana’s life and teachings are is a complex one, and, given time constraints, I will refrain from going into it on a book-by-book basis. A number of books of dialogues were published during Sri Ramana’s lifetime, and all of them were checked and edited by Sri Ramana himself. These include Maharshi’s Gospel, Spiritual Instructions, and the talks that precede Sat Darshana Bhashya. One must also put on this list the teachings Sri Ramana gave out that were recorded by Muruganar in Tamil verse. These have been brought out in a book entitled Guru Vachaka Kovai. Though all of these works have Sri Ramana’s imprimatur, they only constitute a small fraction of the published dialogues.

No one ever recorded Sri Ramana speaking because he refused to let any recordings be made. For many years the ashram manager also forbade anyone from taking notes in Sri Ramana’s presence. This meant that many of the dialogues were written down from memory several hours later. There are always going to be errors in a system like this, but I don’t think that there are many serious ones. Sri Ramana’s teachings have been expressed very clearly in his written works and in the few books of dialogues that he vetted during his lifetime. The remaining body of work, which was not checked, is fairly consistent with these approved teachings.

Maalok: In one of the books you wrote or edited I remember reading that Maharshi’s answers to similar questions by different devotees were not necessarily the same because they were guided by the state of mind of the questioner, rather than the question itself. Could you comment on this, based on your own experience of watching enlightened people teach?

David: If you drop ten people at random in a big city and have them ask people in their neighborhood, ‘How do I get to the city center?’ each person will be given a different set of directions, and all the instructions will be correct. People who start from different places need different instructions to get to the same destination.

If you sit in the presence of an enlightened teacher and ask, ‘What do I have to do to get enlightened?’ that teacher can immediately see where you are spiritually, and what you need to do to make progress. The reply will be based on what he or she sees in your mind, not on some prescribed formula that is handed out to everyone. In some therapy groups there are tried-and-tested techniques that are given out to everyone – the twelve-step approach for recovering alcoholics is a good example – but you don’t find that kind of approach with enlightened teachers.

That’s one answer to your question. One can also say that enlightened people respond to the state of the mind of the person in front of them, not just to the question it asks. A person asking an apparently polite and respectful question may be hiding his true feelings. He may be trying to test the teacher; he may be trying to provoke him, and so on. Quite often, the teacher will respond to those inner feelings, rather than the question itself. Since only the teacher can really see what is going on in people’s minds, replies and responses often appear to be random or arbitrary to other people who are watching or listening. Ramana Maharshi once quoted, with approval, a verse that said, in effect, ‘The enlightened one laughs with those who joke, and cries with those who grieve, all the time being unaffected by the laughter and the grief’.

It is often the inner mood of a questioner that determines the emotional tone of an exchange with a teacher. There are records of Ramana Maharshi, who was normally quiet and unprovokable, jumping off his sofa and chasing people out of the room because he could see that they had come to him with a hidden agenda, perhaps anger, or a desire to demonstrate the superiority of their own ideas. Other people couldn’t see this aggression at all because it was well hidden.

I watched a woman approach Papaji a few years ago with what appeared to be a sensible, spiritual question. He exploded with anger, said that she was only interested in sex and told her to go away. We were all quite shocked because this was her first day, her first meeting. Later that day I spoke to the woman she had come with and asked her how her friend had dealt with this extreme reaction.

She laughed and said, ‘I’m so glad Papaji reacted like that. Every year she comes to India and goes to a new ashram, pretending to be interested in the teacher and the teachings, but every year she starts an affair with some devotee. That’s the real reason why she comes. After a few months she gets bored and leaves. I’m so happy that someone has finally seen through her game.’

I have witnessed countless strange reactions such as these in the teachers I have been with, all of them caused by hidden thoughts and desires that none of the rest of us could see.

There is something else that is going on when you sit in front of a true teacher. There is an effortless transmission of peace that stills the mind and brings an intense joy to the heart. None of this will be recorded in the dialogue that is going on between the two of you. It is something very private, and only the two of you are in on the secret. Words may be exchanged but the real communication is a silent one. In such cases the teacher is often reacting to the temporary absence of your mind, rather than the question you asked a few minutes before, but who else can see this?

Let me give you an example from my own experience. In the late 1970s I sat with a little-known teacher called Dr Poy, a Gujurati who lived in northern Bombay. On my first meeting I asked him what his teachings were and he replied, ‘I have no teachings. People ask questions and I answer them. That is all.’

I persevered: ‘If someone asks you ”How do I get enlightened?”, what do you normally tell them?’

‘Whatever is appropriate,’ he replied.

After a few more questions like this, I realised that I wasn’t going to receive a coherent presentation of this man’s teachings, assuming of course that he had any. He was a good example of what I have just been talking about. He didn’t have a doctrine or a practice that he passed out to everyone who came to see him. He simply answered all questions on a case-by-case basis.

I sat quietly for about ten minutes while Dr Poy talked in Gujurati to a couple of other visitors. In those few minutes I experienced a silence that was so deep, so intense, it physically paralysed me.

He turned to me and said, smiling, ‘What’s your next question?’

He knew I was incapable of replying. His question was a private joke between us that no one else there would have understood. I felt as if my whole body had been given a novocaine injection. I was so paralysed, in an immobilised, ecstatic way, I couldn’t even smile at his remark.