This is an extract from the first chapter of Living by the Words of Bhagavan. The words in roman are Annamalai Swami’s. The explanations of philosophical or cultural topics that appear as paragraphs in italics are my editorial comments:

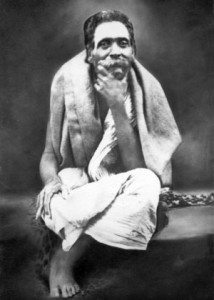

Sometime in 1928, when I was twenty-one years old, a wandering sadhu passed through the village. He gave me a copy of Upadesa Undiyar that contained a photo of Sri Ramana Maharshi. As soon as I saw that photo, I had the feeling that this was my Guru. Simultaneously, an intense desire arose within me to go and see him.

Upadesa Undiyar is a thirty-verse philosophical poem written by Ramana Maharshi in Tamil. It was first published in 1927, about a year before Annamalai Swami got to see it. Upadesa Saram is Sri Ramana’s Sanskrit rendering of the same work. Some of the English translations which appear under the title Upadesa Saram are actually translations of Upadesa Undiyar, the original Tamil work.

That night I had a dream in which I saw Ramana Maharshi walking from the lower slopes of Arunachala to the old hall. At the threshold of the old hall he washed his feet with the water that was in his water pot. I came near him, prostrated at his feet, and then went into a kind of swoon because the shock of having darshan was too much for me. As I was lying on the ground with my mouth open, Bhagavan poured water from his pot into my mouth. I remember repeating the words ‘Mahadeva, Mahadeva’ [one of the names of Siva] as the water was being poured in. Bhagavan gazed at me for a few seconds before turning to go into the hall.

The terms ‘hall’ and ‘old hall’ refer to the building in which Sri Ramana lived and taught between 1928 and the late 1940s. Bhagavan is a Sanskrit word meaning ‘Lord’. Most devotees addressed Sri Ramana as ‘Bhagavan’. They would also use this title when they referred to him in the third person.

When I woke the next morning I decided that I should go immediately to Bhagavan and have his darshan. After informing my parents that I was planning to leave the village, I went to the Bhajan Math to say goodbye to all the people there. Several of them began to cry because they had a strong suspicion that I would not return. I asked for their permission to leave, received it, and left the village that evening. I never went back. Some of the devotees, realising that I had no funds to support myself, collected some money and gave it to me as a parting present.

I had decided to walk twenty-five miles to a nearby town called Ullunderpettai because I had heard that there was a train from there to Tiruvannamalai, the town where Ramana Maharshi lived. However, before I began my journey, a convoy of twelve bullock carts passed through the village on their way to Ullunderpettai. The devotees in the village talked to one of the cart drivers and arranged for me to get a ride in his cart. The journey took all night but I was much too excited to sleep. I spent the entire night sitting in the cart, thinking about Bhagavan.

In Ullunderpettai I shared my food with the cart drivers before boarding the train for Tiruvannamalai. I had originally intended to go straight there, but when one of the passengers informed me that the Sankaracharya was camping near one of the towns on the train route, I decided to see him first and get his blessings. I got down at Tirukoilur [fifteen miles south of Tiruvannamalai] and made my way to Pudupalayam, the village where the Sankaracharya was staying. I found the Sankaracharya, did namaskaram to him and told him that I had had his darshan in Vepur.

A namaskaram is either a prostration or a gesture of respect in which one puts the palms of one’s hands together with the thumbs on the breastbone. Whenever the term occurs in this book it is used in the former sense.

The Sankaracharya gazed at me for a few seconds. Then, with a smile of recognition he said, ‘Yes, I remember you’.

‘I am on my way to see Ramana Bhagavan,’ I told him. ‘Please give me your blessings.’

The Sankaracharya seemed very pleased to hear the news. ‘Very good!’ he exclaimed.

He turned to one of his attendants and asked him to give me some food. After I had finished eating, the Sankaracharya put some vibhuti on a plate and put his palm on it to bless it. He then put half a coconut and eleven silver coins on the plate and presented it to me. I took the money, the vibhuti and the coconut before returning the plate to him.

Feeling that I had now got the blessings which I had sought, I prostrated to him, left the village, and continued my journey to Tiruvannamalai. On my arrival in Tiruvannamalai I was told that there was another great saint there called Seshadri Swami and that it would be very auspicious if I could have his darshan before proceeding to Sri Ramanasramam, the ashram where Ramana Maharshi lived.

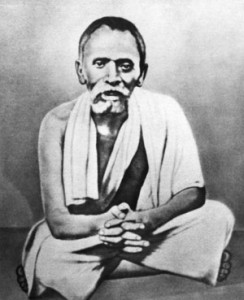

Seshadri Swami, like Ramana Maharshi, came to Arunachala in his youth and stayed there till his death. In his wanderings around the town of Tiruvannamalai he generally behaved in such an eccentric way, many people thought he was mad. However, he redeemed himself in the eyes of the local people by having an astonishing array of supernatural powers which he openly flaunted. Though some of his power was used in traditional ways such as performing miraculous cures, he was more inclined to display it in a bizarre and unpredictable fashion. For example, he would sometimes vandalise shops in the Tiruvannamalai bazaar as an act of blessing. Shop owners welcomed his destructive behaviour because they had found from experience that the damage would be more than paid for in the weeks that followed by either a vast increase in profits or by the repayment of long-forgotten loans.

When Ramana Maharshi came to Tiruvannamalai in 1896, Seshadri Swami was one of the first people to recognise his greatness. He tried to protect Bhagavan from unwanted disturbances and sometimes referred to him as his younger brother.

Bhagavan held Seshadri Swami in high esteem. After Annamalai Swami had told Bhagavan about his meeting with Seshadri Swami (which is described in the next few paragraphs of Annamalai Swami’s account) Bhagavan commented, ‘There is not a single place in this town that has not been visited by Seshadri Swami, but he was never caught in maya [illusion]’.

Seshadri Swami died in January 1929, a few months after Annamalai Swami arrived in Tiruvannamalai. His samadhi, which still attracts large crowds, is about 400 metres from Sri Ramanasramam.

In his account of their meeting Annamalai Swami mentions that he met Seshadri Swami in a mandapam. A mandapam is a Hindu architectural structure, usually a hall supported by stone pillars. A mandapam always has a roof but the sides are generally open.

Seshadri Swami did not stay in any particular place but I soon managed to locate him in a mandapam which was near the main temple. He was easy to find because there was a crowd of about 40-50 people outside the mandapam waiting for him to come out. He had apparently locked himself in. When I peeped in through one of the windows I saw him continuously circling one of the pillars inside. After doing this for about ten minutes, he came outside, sat on a rock, and crossed his legs. I had brought a laddu [a large spherical sweet] which I wanted to give him but I wasn’t sure what to do with it. Seshadri Swami must have sensed my indecision because he looked at me and indicated by a gesture that I should place the laddu on the ground in front of him.

Seshadri Swami had obviously been chewing betel nut for some time. A mixture of the red juice and his saliva was dribbling out of his mouth, soaking his beard, and dripping onto the ground.

Betel is a hard, dark-red nut. Its juice is supposed to aid digestion. It is often eaten along with a lime-coated green leaf. In this combination it is known as ‘pan’.

Seshadri Swami picked up my laddu, smeared it with the saliva-and-betel juice that was staining his beard, and threw it onto the nearby road. As it broke on the ground, the crowd raced towards it and collected the pieces as prasad. I also managed to collect and eat a piece.

Anything which is offered to a deity or a holy man becomes prasad when it is returned to the donor or distributed to the public. Food is the most common form of prasad.

A group of local people appeared to be angry with Seshadri Swami. He silenced them by tossing some stones in their direction. These stones, instead of following a normal trajectory, bobbed and danced around their heads like butterflies. The men he had thrown the stones at got afraid and ran away. They clearly didn’t want to tangle with a man who possessed supernatural powers of this kind.

When I went back and stood before Seshadri Swami again, he started to shout at me in a very abusive way.

‘This fool came to Tiruvannamalai! Stupid man! What did he come here for?’

He carried on in this vein for some time, implying that I was wasting my time coming to Tiruvannamalai. I thought that I must have committed a great sin to have a great saint insult me like this. I started to cry because I thought that I had been cursed.

Eventually a man called Manikka Swami, who was Seshadri Swami’s attendant, came up to me and consoled me by saying, ‘Your trip to Tiruvannamalai will be successful. You will get whatever you have come for. This is Seshadri Swami’s way of blessing you. When he abuses people like this he is really blessing them.’

Manikka Swami then took me to a hotel which was owned by a devotee of Seshadri Swami.

He told the owner, ‘Seshadri Swami has just showered his blessings on this man. Please give him a free meal.’

I was not feeling particularly hungry, but when the owner insisted I sat down and ate some of his food. When I had eaten enough to satisfy him, I got up and walked the remaining distance to Sri Ramanasramam.

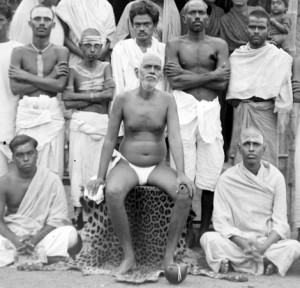

I arrived there at about 1 p.m. As I approached the hall, part of the dream I had had in my village repeated itself in real life. I saw Bhagavan walk down the hill, cross the ashram and pause outside the hall while he washed his feet with water from his kamandalu [water pot]. Then he went inside. I sprinkled some of this water on my head, drank a little, and then went inside to meet him. Bhagavan was sitting on his couch while an attendant called Madhava Swami dried his feet with a cloth. Madhava Swami went out a few minutes later, leaving Bhagavan and me alone in the hall. I had bought a small packet of dried grapes and some sugar candy to give him. I placed them on a small table that was next to Bhagavan’s sofa and prostrated to him. When I stood up I saw that Bhagavan was eating a little of my offering. As I watched him swallow, the thought came to me that my offering was going directly into Siva’s stomach.

I sat down and Bhagavan gazed at me in silence for about 10-15 minutes. There was a great feeling of physical relief and relaxation while Bhagavan was looking at me. I felt a wonderful coolness pervade my body. It was like immersing myself in a cool pool after being outside in the hot sun.

I asked for permission to stay and this was readily granted. A small hut was given to me and for the first week I stayed there as a guest of the ashram. During those first few days I either gathered flowers for the ashram’s pujas or just sat with Bhagavan in his hall.

As the days passed I became more and more convinced that Bhagavan was my Guru. Feeling a strong urge to settle down in the ashram, I asked Chinnaswami, Bhagavan’s younger brother, if I could work in the ashram. Chinnaswami granted my request and said that I could serve as Bhagavan’s attendant. At that time Madhava Swami was doing the job by himself.

Chinnaswami told me, ‘Madhava Swami is the only attendant at the moment. Whenever he goes out of the hall or goes for a rest you should stay with Bhagavan and attend to all his needs.’

About ten days after my arrival I asked Bhagavan, ‘How to avoid misery?’

This was the first spiritual question I ever asked him.

Bhagavan replied, ‘Know and always hold on to the Self. Disregard the body and the mind. To identify with them is misery. Dive deep into the Heart, the source of being and peace, and establish yourself there.’

I then asked him how I could attain Self-realisation and he gave me a similar answer: ‘If you give up identifying with the body and meditate on the Self, which you already are, you can attain Self-realisation.’

As I was pondering on these remarks Bhagavan surprised me by saying, ‘I was waiting for you. I was wondering when you would come.’

As a newcomer I was still too afraid of him to follow this up by asking him how he knew, or how long he had been waiting. However, I was delighted to hear him speak like this because it seemed to indicate that it was my destiny to stay with him.

A few days later I asked another question: ‘Scientists have invented and produced aircraft which can travel at great speeds in the sky. Why do you not make and give us a spiritual aircraft in which we can quickly and easily cross over the sea of samsara?’

Samsara is the seemingly endless cycle of birth and death through different incarnations. It can also be taken to mean worldly illusion or entanglement in worldly affairs.

‘The path of self-enquiry,’ replied Bhagavan, ‘is the aircraft you need. It is direct, fast and easy to use. You are already travelling very quickly towards realisation. It is only because of your mind that it seems that there is no movement. In the old days, when people first rode on trains, some of them believed that the trees and the countryside were moving and that the train was standing still. It is the same with you now. Your mind is making you believe that you are not moving towards Self-realisation.’

Philosophically, Bhagavan’s teachings belong to an Indian school of thought which is known as Advaita Vedanta. (He himself, though, would say that his teachings came from his own experience, rather than from anything he had heard or read.) Bhagavan and other advaita teachers teach that the Self (Atman) or Brahman is the only existing reality and that all phenomena are indivisible manifestations or appearances within it. The ultimate aim of life, according to Bhagavan and other advaita teachers, is to transcend the illusion that one is an individual person who functions through a body and a mind in a world of separate, interacting objects. Once this has been achieved, one becomes aware of what one really is: immanent, formless consciousness. This final state of awareness, which is known as Self-realisation, can be achieved, in Bhagavan’s view, by practising a technique he called self-enquiry.

This technique needs to be explained in some detail since it is mentioned several times in Annamalai Swami’s narrative. The following explanation summarises both the practice and theory behind it. It is taken from No Mind – I am the Self, pp. 1-15.

It was Sri Ramana’s basic thesis that the individual self is nothing more than a thought or an idea. He said that this thought, which he called the ‘I’-thought, originates from a place called the Heart-centre, which he located on the right side of the chest in the human body. From there the ‘I’-thought rises up to the brain and identifies itself with the body: ‘I am this body.’ It then creates the illusion that there is a mind or an individual self which inhabits the body and which controls all its thoughts and actions. The ‘I’-thought accomplishes this by identifying itself with all the thoughts and perceptions that go on in the body. For example, ‘I’ (that is, the ‘I’-thought) am doing this, ‘I’ am thinking this, ‘I’ am feeling happy, etc. Thus, the idea that one is an individual person is generated and sustained by the ‘I’-thought and by its habit of constantly attaching itself to all the thoughts that arise. Sri Ramana maintained that one could reverse this process by depriving the ‘I’-thought of all the thoughts and perceptions that it normally identifies with. Sri Ramana taught that this ‘I’-thought is actually an unreal entity, and that it only appears to exist when it identifies itself with other thoughts. He said that if one can break the connection between the ‘I’-thought and the thoughts it identifies with, then the ‘I’-thought itself will subside and finally disappear. Sri Ramana suggested that this could be done by holding onto the ‘I’-thought, that is, the inner feeling of ‘I’ or ‘I am’ and excluding all other thoughts. As an aid to keeping one’s attention on this inner feeling of ‘I’, he recommended that one should constantly question oneself ‘Who am I?’ or ‘Where does this “I” come from?’ He said that if one can keep one’s attention on this inner feeling of ‘I’, and if one can exclude all other thoughts, then the ‘I’-thought will start to subside into the Heart-centre.

This, according to Sri Ramana, is as much as the devotee can do by himself. When the devotee has freed his mind of all thoughts except the ‘I’-thought, the power of the Self pulls the ‘I’-thought back into the Heart-centre and eventually destroys it so completely that it never rises again. This is the moment of Self-realisation. When this happens, the mind and the individual self (both of which Sri Ramana equated with the ‘I’-thought) are destroyed for ever. Only the Atman or the Self then remains.

The following practical advice was written by Bhagavan himself in the 1920s. Taken from Be As You Are (1992 ed., p. 56) it encapsulates his basic teachings on the subject. All new visitors were encouraged to read the essay (entitled Who am I?) that this extract is taken from. It was published as a pamphlet and Bhagavan encouraged the manager of the ashram to sell it cheaply in many languages so that all new people could have an affordable and authoritative summary of his practical teachings.

The mind will subside only by means of the enquiry ‘Who am I?’ The thought ‘Who am I?’, destroying all other thoughts, will itself be finally destroyed like the stick used for stirring the funeral pyre. If other thoughts arise one should, without attempting to complete them, enquire, ‘To whom did they rise?’ What does it matter how many thoughts rise? At the very moment that each thought rises, if one vigilantly enquires, ‘To whom did this rise?’, it will be known ‘To me’. If one then enquires ‘Who am I?’, the mind will turn back to its source and the thought which had risen will also subside. By repeatedly practising thus, the power of the mind to abide in its source increases.

In the years that followed I had many other spiritual talks with Bhagavan but his basic message never changed. It was always, ‘Do self-enquiry, stop identifying with the body and try to be aware of the Self which is your real nature’.

Prior to these early conversations I had been spending several hours each day performing elaborate pujas and anushtanas.