When I asked Bhagavan if I should continue with them he replied, ‘You need not do any of these pujas any more. If you practise self-enquiry, that alone will be enough.’

My duties as an attendant were fairly simple and I soon learned what to do. When devotees brought offerings I had to return some of them as prasad. I also had to ensure that the men sat on one side of the hall and the women on the other. When Bhagavan went out, one attendant would go with him while the other stayed behind to clean the hall. We had to keep the cloths that were on his sofa clean; we had to wash his clothes; in the early morning we had to heat water for his bath; and if he went for any walks during the day, one of us would always accompany him.

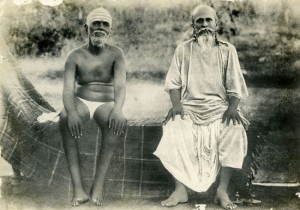

Bhagavan’s clothes consisted of kaupinas and dhotis. For most of the time he only ever wore a kaupina, a strip of cloth which covers the genitals and the centre of the buttocks. It was held in place by another strip of cloth which was tied around his waist. Occasionally, when it was cold, he would wrap a dhoti around himself. Dhotis are strips of cloth which are usually worn like skirts. Bhagavan preferred to tie his in such a way that it extended from his armpits to his thighs.

When he arrived in Tiruvannamalai in 1896, Bhagavan threw away all his personal possessions, including his clothes. He never wore normal clothes again.

Bhagavan would usually go for a short walk about three times a day. Sometimes he would go to Palakottu, an area adjacent to Sri Ramanasramam where some of his devotees lived, and sometimes he would walk on the lower slopes of Arunachala. He had stopped going for giri pradakshina in 1926, but he still occasionally went for a long walk.

Walking around a person or an object in a clockwise direction as an act of veneration or worship is called pradakshina. Giri means hill or mountain. In this context giri pradakshina means walking around the mountain of Arunachala. There is an eight-mile road around the base of the mountain. Thousands of devotees regularly use this route to perform giri pradakshina.

I remember going with him twice to the Samudram Lake, which is about a mile to the south-west of the ashram. We went once when it overflowed and once when the nearby pumping station was opened. I also once accompanied him to the forest near Kattu Siva Ashram, about two miles from the ashram. On that occasion Ganapati Muni came with us because Bhagavan wanted to show him a special tree which grew there. For that particular trip we slipped out of the ashram while everyone was having his after-lunch sleep. If we had been spotted, everyone in the ashram would have tried to come with us. Bhagavan always enjoyed his walks. He used to say that if he didn’t walk on the hill at least once a day, his legs would get stiff and painful.

Bhagavan only slept about four to five hours every day. This meant long working hours for the attendants because one of us had to be on duty all the time he was awake. He never slept after lunch, whereas most of his devotees did. Bhagavan would often utilise this quiet time of the day to feed all the ashram’s animals or to tour the ashram in order to inspect any building works that were in progress.

Bhagavan would generally go to sleep at about 10 p.m. but he would usually wake up at about 1 a.m. and go out to urinate. When he returned he would often sit for half an hour or an hour before going back to sleep again. Then, sometime between 3 and 4 a.m., he would wake up and go to the kitchen to cut vegetables.

These night-time toilet trips became something of a ritual for both Bhagavan and the attendants. When he woke up, the attendant had to take Bhagavan’s kamandalu, fill it with hot water, and give it to him. The water was heated on a kumutti [charcoal brazier] which was always kept by the side of Bhagavan’s couch. The attendant then had to give Bhagavan his stick and his torch, hold the door open for him, and follow him out into the night. Bhagavan usually went to a place where Muruganar’s samadhi [grave and shrine] is now located because we had no proper toilets in those days. When he returned, the attendant had to clean Bhagavan’s feet with a cloth.

Bhagavan would never wake his attendants up. It was their duty to be awake and ready at 1 a.m. One morning I failed to wake up because I had had a dream in which I woke up at 1 a.m. and performed all the duties I have just described. At the end of my dream I went back to sleep, satisfied that I had done my work. I was woken up sometime later by Bhagavan returning alone to the hall. I apologised for oversleeping and told Bhagavan that I had dreamt about doing all the usual services for him and had then gone back to sleep.

Bhagavan laughed and said, ‘The services you did for the dream swami are for me only’.

When I first came to the ashram there were still some leopards in the area. They rarely came into the ashram but at night they often frequented the place where Bhagavan used to urinate. I remember him meeting one on one of his nocturnal trips. He was not the least bit afraid. He just looked at the leopard and said, ‘Poda! [Go away!]’. And the leopard just walked away.

Soon after I came I was given a new name by Bhagavan. My original name had been Sellaperumal. One day Bhagavan casually mentioned that I reminded him of a man called Annamalai Swami who had been his attendant at Skandashram. He started to use this name as a nickname for me. When the devotees heard this, they all followed suit and within a few days my new identity was firmly established.

Bhagavan lived at Skandashram, on the eastern slopes of Arunachala, from 1916-22. Annamalai Swami died there during a plague outbreak in 1922.

When I had been an attendant for about two weeks the Collector from Vellore [the senior-most civil servant from the local district headquarters] came to have Bhagavan’s darshan. He was called Ranganathan and he brought a large plate of sweets as an offering to Bhagavan. Bhagavan asked me to distribute the sweets to everyone in the ashram, including those who were not then present in the hall. While I was distributing the sweets to the people outside the hall, I went to a place where no one could see me and secretly helped myself to about double the quantity that I was serving to everyone else. When the distribution was completed, I went back to the hall and put the plate underneath Bhagavan’s sofa.

Bhagavan looked at me and said, ‘Did you take twice as much as everyone else?’

I was shocked because I was sure that no one had seen me do it.

‘I took it when no one was looking. How does Bhagavan know?’

Bhagavan made no answer. This incident made me realise that it is impossible to hide anything from Bhagavan. From that time on I automatically assumed that Bhagavan always knew what I was doing. This new knowledge made me more alert and more attentive to my work because I didn’t want to commit any similar mistakes again.

It was also the attendants’ job to protect Bhagavan from eccentric or misguided devotees. I remember one incident of this kind very clearly. A boy about twenty years of age appeared in the hall wearing only a loincloth. After announcing to everyone that he also was jnani, he went and sat on the sofa next to Bhagavan. Bhagavan made no comment about this, but very soon afterwards he got up and went out of the hall. While he was away I took the opportunity to eject this impostor. All of us in the hall were annoyed by his arrogance and his presumption, and I must admit that I handled him rather roughly while I was throwing him out. I also forbade him from coming into the hall again. When peace had been finally restored Bhagavan came back into the hall and resumed his usual position on the sofa.

I was very happy to have found such a great Guru as Bhagavan. As soon as I saw him I felt that I was looking at God Himself. However, initially, I was not very impressed either by the ashram or by the devotees who had gathered around him. The management seemed to be very autocratic and most of the devotees didn’t seem to have much interest in the spiritual life. So far as I could see, they were primarily interested in gossiping. These early impressions disturbed me.

I thought to myself: ‘Bhagavan is very great. But if I live in the company of these people, I may lose the devotion that I already have.’

I came to the conclusion that it would not be spiritually beneficial for me to associate with people who didn’t seem to have much devotion. I know now that this was a very arrogant attitude, but those were my true feelings at the time. These thoughts disturbed me so much that for three or four nights I was unable to sleep. I finally came to the conclusion that I would keep Bhagavan as my Guru but live somewhere else. I remember thinking: ‘I will go and do meditation on the Self somewhere else.

Without having the distracting friendship of any human beings, I will go to an unknown place and meditate on God. I will go for bhiksha [beg for food] and lead a solitary life.’

About three weeks after I first came to the ashram, I left to take up my new life. I told no one, not even Bhagavan, about my decision. I left at 1 a.m. on a full-moon night and started to walk towards town. I went straight through the town, past Easanya Math [a monastic institution on the north-east side of Tiruvannamalai] and started walking towards Polur. I had no particular destination in mind; I just wanted to get away from the ashram. I spent the whole night walking and reached Polur [twenty miles north of Tiruvannamalai] just after dawn. The walk had made me very hungry so I decided to go for bhiksha in the town. It was not a great success. I begged at about 500 different houses but no one gave me any food. One man told me that I should go back to Tiruvannamalai while another man, who was serving a meal when I approached him, shouted at me, telling me to go away. Eventually, I gave up and walked to the outskirts of the town. I found a well in a field and spent about half an hour standing in it, with the water up to my neck, hoping that the coldness of the water would take my hunger pains away. It didn’t work. Then I made my way to the samadhi [shrine] of Vitthoba and sat there for a while.

Vitthoba was an eccentric saint, rather like Seshadri Swami, who lived in Polur in the first decades of this century. He died a few years before Annamalai Swami went there.

I finally got something to eat when an old lady came to do puja.

She looked at me and said, ‘It seems as if you are very hungry. Your eyes are starting to sink into your face. I don’t have much myself but I can give you some ragi [millet] gruel.’

As she was saying this she gave me about one and a half tumblers of the ragi gruel to drink. It didn’t do much for my hunger pangs but I was still very happy to receive it. The long walk and the lack of food had made me very tired. As I sat there I began to question the wisdom of leaving Bhagavan. It was clear that things had not turned out in the way that I had expected. This indicated to me that the decision might not have been correct. I formulated a plan that I thought would test whether my decision had been correct or not. I took a large handful of flowers, placed them on the samadhi of Vitthoba and started to remove them two at a time. I had decided in advance that if there were an odd number of flowers I would return to Bhagavan. If there were an even number I would carry on with my original plan. When the result indicated that I should go back to Bhagavan, I immediately accepted the decision and started walking towards Tiruvannamalai.

Once I had accepted that my prarabdha [destiny] was to stay with Bhagavan, my luck began to change. As I was walking into town, a hotel owner invited me into his hotel and gave me a free meal and some money. He even prostrated to me. I had decided to return to Tiruvannamalai by train because I wanted to get back to Bhagavan as soon as possible, but before I could reach the station some more people invited me into their house and asked me to eat. I ate a little food there and then excused myself on the grounds that I had just eaten a big meal. I had decided to try to travel without a ticket, wrongly assuming that the money I had been given would not be enough for the journey. My good luck continued on the train. Halfway to Tiruvannamalai a ticket inspector came to inspect all the tickets. I seemed to be invisible to him, for I was the only person in the carriage who was not asked to produce a ticket.

A similar thing happened at the end of the journey. When I paused in front of the ticket collector on the station platform he said, ‘You have already given your ticket. Go! You are holding the others up!’

Thus, by Bhagavan’s grace, I escaped on both occasions. I walked the remaining distance to the ashram. On my arrival I went straight to Bhagavan, prostrated before him, and told him everything that had happened. Bhagavan then confirmed that it was my destiny to stay at Ramanasramam.

Looking at me he said, ‘You have work to do here. If you try to leave without doing the jobs that are destined for you, where can you go?’

After saying this Bhagavan looked at me intently for a period of about fifteen minutes. As he was looking at me I heard a verse repeating itself inside me. It was so loud and clear it felt as if someone had implanted a radio there. I had not come across this verse before. I only discovered later that it was one of the verses from Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham [one of Bhagavan’s philosophical poems which deals with the nature of reality]. The verse says:

The supreme state which is praised and which is attained here in this life by clear self-enquiry, which rises in the Heart when association with a sadhu is gained, is impossible to attain by listening to preachers, by studying and learning the meaning of the scriptures, by virtuous deeds, or by any other means.

Although the word ‘sadhu’ generally refers to someone who is pursuing a spiritual career full-time, in this context it means someone who has realised the Self.

The meaning was very clear: staying near Bhagavan would be more beneficial for me than doing sadhana alone in some other place.

At the end of the fifteen minutes I did namaskaram to Bhagavan and said, ‘I will do whatever work you order me to do, but please also give me moksha [liberation]. I do not want to become a slave to maya [illusion].’

Bhagavan made no reply but I was not perturbed by his silence. Somehow, the mere asking of the question had made my mind peaceful. Bhagavan then asked me to go and eat some food. I replied that I was not hungry because I had recently eaten.

I added: ‘I don’t want food. All I want is moksha, freedom from sorrow.’

This time Bhagavan looked at me, nodded, and said, ‘Yes, yes’.

This verse from Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham on the greatness of association with Self-realised beings is one of five on the subject which Bhagavan incorporated in the poem. He discovered the original Sanskrit verses on a piece of paper which had been used to wrap some sweets. He liked the ideas they conveyed so much he translated them into Tamil himself and put them at the beginning of Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham. The other four verses are as follows:

By satsang [association with reality or, more commonly, with realised beings] the association with the objects of the world will be removed. When that worldly association is removed, the attachments or tendencies of the mind will be destroyed. Those who are devoid of mental attachment will perish in that which is motionless. Thus they attain jivan mukti [liberation while still alive in the body]. Cherish their association.

If one gains association with sadhus, of what use are all the religious observances? When the excellent cool southern breeze itself is blowing, what is the use of holding a hand-fan?

Heat will be removed by the cool moon, poverty by the celestial wish-fulfilling tree, and sin by the Ganges. But know that all these, beginning with heat, will be removed merely by having the darshan [sight] of incomparable sadhus.

Sacred bathing places, which are composed of water, and images of deities, which are made of stone and earth, cannot be comparable to those great souls [mahatmas]. Ah, what a wonder! The bathing places and deities bestow purity of mind after countless days, whereas such purity is instantly bestowed upon people as soon as sadhus see them with their eyes.

Several years after this incident Annamalai Swami asked Bhagavan about one of these verses:

We know where the moon is, and we know where the Ganges is, but where is this wish-fulfilling tree?’

‘If I tell you where it is,’ replied Bhagavan, ‘will you be able to leave it?’

I was puzzled by this peculiar answer but I didn’t pursue the matter. A few minutes later I opened a copy of Yoga Vasishta which was lying next to Bhagavan. On the first page I looked at I found a verse which said, ‘The jnani is the wish-fulfilling tree’. I immediately understood Bhagavan’s strange answer to my question. Before I had a chance to tell Bhagavan about this, he looked at me and smiled. He seemed to know that I had found the right answer. I told Bhagavan about the verse but he made no comment. He just carried on smiling at me.