Bhagavan had another reason for liking Sorupananda. In a story he told on several occasions Sorupananda quietened the minds of a group of skeptical and doubting visitors simply by keeping quiet and abiding as the Self. Here is the version he told in Day by Day with Bhagavan, 21st November1945:

Tattuvaraya [Sorupanananda’s chief disciple] composed a bharani [a kind of poetical composition in Tamil] in honour of his Guru Sorupananda and convened an assembly of learned pandits to hear the work and assess its value. The pandits raised the objection that a bharani was only composed in honour of great heroes capable of killing a thousand elephants, and that it was not in order to compose such a work in honour of an ascetic. Thereupon the author said, ‘Let us all go to my Guru and we shall have this matter settled there’. They went to the Guru and, after all had taken their seats, the author told his Guru the purpose of their coming there. The Guru sat silent and all the others also remained in mauna. The whole day passed, night came, and some more days and nights, and yet all sat there silently, no thought at all occurring to any of them and nobody thinking or asking why they had come there. After three or four days like this, the Guru moved his mind a bit and thereupon the assembly regained their thought activity. They then declared, ‘Conquering a thousand elephants is nothing beside this Guru’s power to conquer the rutting elephants of all our egos put together. So certainly he deserves the bharani in his honour!’

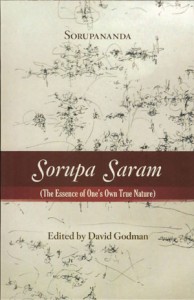

Sorupananda articulated his experience of the Self in the verses that comprise Sorupa Saram. The format is a brief question and answer, followed by an elaboration on the answer. Here is an excerpt (verses 14-19) that gives a taste of the elegant advaitic purity of Sorupananda’s replies. It is not hard to see and understand why Bhagavan appreciated these verses enough to put them on a reading list for Annamalai Swami:

Question: What is the benefit arising from this experience [of the Self]?

Answer: It is becoming the ruler of the kingdom of liberation.I obtained the supreme lordship that is never lost. I burned up the pair of opposites – happiness and misery. I gave up the life of the body-forest, which tormented the mind. I entered and occupied the house of liberation.

Question: What play will this king witness on his stage?

Answer: He will witness the dance of the three avasthas [waking, dreaming and sleeping].In the waking state I will witness the dance of the five organs of action and the five organs of sense. In dream I will witness the dance of the mind. In thought-free sleep I will dance the object-free void-dance. However, I will [always] remain as the exalted essence [the Self].

Question: Where was this experience when you were [formerly] regarding happiness and misery as ‘I’?

Answer: Then, too, I was remaining as the Self. I was nothing else.Who was the one who remained as [the ego] ‘I’? If I see him, I will not allow him to take up the form of the body. Only the ‘I’ whose form is consciousness is the real ‘I’. All other ‘I’s will get bound to a form and go through birth and death.

Question: The Self is immutable. Will it not get bound if it gets involved in activities?

Answer: As the Self remains a witness, like the sun, it will not get bound.Even if I bear the burdens of the family and have them follow me like a shadow, or even if the cloud called ‘maya’ veils, I am, without doubt, the sun of knowledge, self-shining as pure light and remaining as the witness [of the world].

Question: But the jnani is not remaining motionless like the sun.

Answer: He also remains actionless.Whatever comes, whatever actions are performed, in whatever I may delight, I am only pure consciousness, remaining aloof and aware, without becoming any of them.

Question: All things move because the Self makes them move. Hence, is there bondage for the Self?

Answer: Like the rope that makes the top spin, there is no bondage for it.In the same way that a top is made to spin by a rope, desires fructify in my presence. But, like the rope that is used to spin the top, I will not merge with them. I have rid myself of their connection. I became my own Self. My bondage is indeed gone.

The relationship between Sorupananda and Tattuvaraya, his chief disciple, had several similarities to that which existed between Bhagavan and Muruganar. In both cases a mostly silent and powerful Guru brought about the liberation of a mature disciple who went on to write thousands of verses that either praised the Guru, recorded his teachings, or expressed some aspect of his experience of the Self. After we had completed our work on Sorupa Saram, Venkatasubramanian, Robert and I also translated a few of the thousands of verses that have been attributed to Tattuvaraya. These were published online and in The Mountain Path.

One other not-so-well-known Tamil saint has been the target of our research and translation activities in recent years. His name is Guhai Namasivaya, and he lived on Arunachala about four hundred years ago. The traditional story of his life reports that he came to Tiruvannamalai from Sri Sailam, Andhra Pradesh. He was accompanied on his journey to Arunachala by Virupaksha Devar, the man who gave his name to Virupaksha Cave. Both were devotees of the same Guru, and both received his permission to relocate from Sri Sailam to Tiruvannamalai. Very little is known about Virupaksha Devar, but Guhai Namasivaya has many stories associated with him, and he has, in addition, composed a significant number of verses in praise of Arunachala. Other than Bhagavan he is the only saint I know of who claimed that he was liberated through the power of Arunachala and who subsequently wrote verses in praise of the mountain, thanking it for the role it had played in his final realisation.

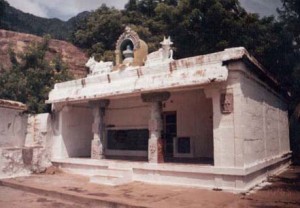

Bhagavan himself stayed in the Guhai Namasivaya Temple, on the lower slopes of Arunachala, for a brief period around 1901. It was there that Sivaprakasam Pillai met him for the first time and recorded the answers that were later published as Who am I? When Bhagavan moved up the hill to Virupaksha Cave, the mantapam next to the samadhi temple of Guhai Namasivaya was taken over by Keerai Patti, an old lady who served food to Bhagavan in the first decade of the last century. It is widely believed that Keerai Patti was the previous incarnation of Lakshmi the Cow, who attained liberation at Ramanasramam in 1948.

I visited the Guhai Namasivaya Temple many times in the 1980s. I found it to be an extraordinarily peaceful and powerful place, even though the street noise from the town of Tiruvannamalai was always drifting up the hill. Curious about the place that had had such an effect on me, I did a little research and found that there were 136 published verses by Guhai Namasivaya that spoke of his experience of Arunachala and his life on the hill.

Sometime in the 1980s I was asked by V. Ganesan, who was then editing The Mountain Path, to locate in the ashram archives a text that related the mythological stories of Tiruchuzhi, the town where Bhagavan was born. As I was hunting for it, I noticed an old handwritten notebook that had ‘Guhai Namasivaya’ written in Tamil letters on the covers. Wondering what it might be, I opened it and found hundreds of Tamil venba verses, all attributed to Guhai Namasivaya. I took the notebook back to the ashram to make further enquiries. The first thing I discovered was that the handwriting in the notebook was Bhagavan’s. This piqued my curiosity even more. I came to the conclusion that Bhagavan had copied these verses into the notebook when he was staying on the hill around 1901. At that time there were still palm-leaf manuscripts in the possession of the owner of the Guhai Namasivaya Temple. These disappeared in the late 1970s when someone who had promised to get them published took them away and was never seen again. It was therefore quite likely that Bhagavan’s notebook was the only place in the world where the vast majority of Guhai Namasivaya’s verses were still recorded.

At the time I was not in a position to do much with them. Robert had disappeared off to England and I had not yet teamed up with Venkatasubramanian, although he had helped me out with a couple of small translation jobs. I put the book aside and decided that at some future date, when I had more time and better resources, I would get back to it.

When I left for Lucknow in early 1993, I thought I would be back in a few weeks. When it became clear that I would be staying there for a long time, I gave the key to my Ramanasramam room to a friend and asked him to clear the room and put everything in storage. I had a trunk full of books and manuscripts that I had borrowed from the ashram library and archives. I asked my friend to return all the books and papers since I didn’t know when I would be back. It took me three years to return. When I finally did return, I opened the trunk that had contained all the manuscripts and papers. It was completely empty except for the Guhai Namasivaya manuscript. I took this as a hint that I should get to work on it and make some effort to bring it out.

Ramaswami Pillai told me a story many years ago. He once asked Bhagavan, ‘How can I tell if choosing a particular course of action is something that I should be doing, or is something that will merely distract me from more important things?’

There is a Tamil tradition that fate or destiny is a load that one carries on one’s head.

Bhagavan replied, ‘Throw if off your head three times, and if it jumps back three times, it is something you have to do.’

Seeing this manuscript, which I had tried to return years before, still sitting in the bottom of my trunk seemed to me at the time to be an illustration of Bhagavan’s story. I had asked for the manuscript to be returned, but there it was, still in the trunk, still demanding my attention. The project had jumped back on my head.

I showed the manuscript to Venkatasubramanian, who copied it out and edited the verses for publication in Tamil. Sri Ramanasramam agreed to print the verses because of their theme (Arunachala) and Bhagavan’s connection with the place where they were composed. Around the time that we were finishing our work on Guru Vachaka Kovai, Venkatasubramanian, Robert and I decided it was finally time to bring out an English translation of all these verses that Bhagavan had taken the trouble to record and preserve more than a century before.

As I write this (July 2014) the verses have all been translated and a long biographical introduction that contains all the known details of Guhai Namasivaya’s life has been completed. The book has not been published yet since I am still writing notes and explanations for the verses that contain obscure religious and cultural references.

Guhai Namasivaya had a famous disciple, Guru Namasivaya, who lived with him on Arunachala before being dispatched to Chidambaram by his Guru to do important renovation in the temple there. Since his disciple, Guru Namasivaya, has his own entertaining hagiography and since he has also written moving verses on Arunachala, we will include a section in our book that will contain the material we have managed to find out on him, along with his most famous poem, Annamalai Venba, which sings of the greatness of Arunachala.

Here are a few sample verses (22, 26, 31, 33, 39, 99) from Annamalai Venba, composed probably in the 16th century. ‘Annamalai’ is the Tamil name for Arunachala. It means ‘unreachable or unapproachable mountain’ a reference to the principal myth of the mountain. In order to demonstrate his superiority over Brahma and Vishnu, Siva manifested as a column of light and asked the other two gods to try to find either his top or his bottom. Both gods failed in their attempts. Siva later condensed the column into the mountain of Arunachala so that devotees and the gods could have a less dazzling form of him to worship.

Mountain who drives out the darkness of spiritual ignorance.

Mountain who, for devotes, illumines what is false.

Mountain in the form of perfect jnana.

Mountain who came to me, a mere dog,

As father, mother and Sadguru:

Annamalai.Celestial Mountain who, coming into the world

As my Guru Om Namasivaya,

Dwells within the heart of this devotee.

Mountain who wipes out the fruits of former deeds.

Mountain who abolishes all the suffering

Of a long succession of births, too numerous to tell:

Annamalai.Mountain who is the delightful sweet honey

Of the pure Siva-jnana,

Which assuages the pangs of hunger.

Mountain who eternally affords His gracious sight to devotees,

Warding off the obscuring waves of illusion:

Annamalai.Majestic Mountain who, as my Guru,

Held me in His sway,

Keeping me from wandering through ever-increasing births,

Placing in my hand sweet, true knowledge,

And uniting his twin feet together upon my head:

Annamalai.Mountain who yields up to the devotees who sing his praises

All the things that they desire,

The foremost of which is liberation.

Mountain clad in lasting glory.

Mountain who, as Sadguru, ruled over me,

Wicked wretch that I am:

Annamalai.Mountain who confers undying liberation.

Mountain who, destroying for his devotees

The indestructible residue of deeds, comforts them,

Decreeing that the impassable ocean of multifarious births

Shall henceforth be still:

Annamalai.

The ‘indestructible residue of deeds’ mentioned in the final verse is a reference to sanchita karma, the residue of karma left over from all previous lifetimes.

And that brings me to the end of my update. I have several other projects in the pipeline, but none is advanced enough to merit inclusion in this account of books published, or about to be published. Maybe, one day, there will be another update.