Michelle: After Be As You Are and No Mind – I am the Self came out, you didn’t publish again for many years. What were you doing?

David: I did do a lot of writing and research during this period but none of it ever made it as far as publication, at least not in book form. I decided that I wanted to edit a book about all the various saints who had been associated with Arunachala over the last 1,500 years. Many great saints have lived and taught here during that period. Their writings exist in Tamil and Sanskrit, but virtually none of their output has ever been published in English. I decided to find as much of this material as possible and then find people who could translate it for me. So many bad or weirdly inexplicable things happened to the various people I co-opted into this scheme, I began to believe that this particular project didn’t have Arunachala’s blessings.

All this happened a long time ago. Let me see if I can remember it all. A friend of mine, Robert Butler, had learned classical, literary Tamil. He volunteered to translate some verses for me, but since he was new to the Tamil translation business, he wanted to have his material checked by someone who knew a lot more Tamil than he did.

I approached Sadhu Om, who was generally regarded as being the best Tamil poet and scholar in the vicinity of Ramanasramam, and asked him if he would be willing to check a few of the verses for me, just to see if Robert’s understanding was good enough for him to continue with his work. Sadhu Om said he was very busy on other work, but he promised he would get round to it at some point. Weeks went by and nothing happened. Then Michael James, who was his chief assistant, approached me and said that Sadhu Om had promised to do them the following day. Michael had put the verses on his desk so that he could start work on them the next morning. That night Sadhu Om had a stroke from which he never recovered. He died a few days later.

Robert, meanwhile, had gone to England to see his family. While he was there, visas were introduced for British and other Commonwealth people. He wanted to come back with an entry visa that would enable him to stay full-time at the ashram where he hoped to continue working with me. I got the president of Ramanasramam to sponsor him with a signed letter that stated that he was coming to India to do voluntary work at the ashram. These visas usually take about three months to process, but his application dragged on for over a year, with no decision forthcoming from the government. Eventually, someone in Delhi checked with Ramanasramam to see if the ashram really was sponsoring him. Someone who didn’t know anything about this arrangement wrote back saying that the ashram had never heard of him, and that he was not coming here to work. That letter effectively left Robert marooned in England because the Indian government was convinced that he had faked his visa application.

I then approached a famous Tamil translator called Vanmikinathan and was delighted when he agreed to help me. I gave him fifty-three verses from the Tevarams that had been composed by famous saints who had been associated with Arunachala in the sixth to ninth centuries. It was tricky stuff to translate, needing expertise in that era of Tamil literature. Vanmikinathan had already translated and published poems from this era, so I was very happy to have him on board. After a few days I received a letter from him that stated that he had completed the work, that he would make a fair copy of it and mail it to me the following day. I was impressed with his speed. A few days later I received another letter from him whose text went approximately as follows:

‘Dear Mr Godman, I translated your verses and left them on my desk, thinking that I would copy them out later. Then a gust of wind came in through the window, picked up your papers and blew them out into the garden. When I went outside to collect them, there was no sign of them anywhere.’

He ended up getting into a protracted dispute with the Ramakrishna Math in Madras over another book he had translated for them, and I lost his services. For a while I was being helped by Ratna Navaratnam, a Sri Lankan scholar who was an expert on old Tamil and a devotee of Bhagavan. I can’t remember why she dropped out. It couldn’t have been anything too bad, or I would remember.

Another foreign scholar, an American woman, was also caught up in this drama. She wanted to do a Ph.D on Arunachala Mahatmyam, the Sanskrit work that records all the puranic stories and legends about Arunachala. There was a plan for her to move to Tiruvannamalai with her son and do all the work here. I remember that at some point she arranged for her son to do a year of French schooling here by post. I arranged all the paperwork at this end. I got her registered at Madras University and arranged for the professor of Sanskrit there to be her nominal thesis supervisor since she couldn’t do graduate work here without one. I went to all this trouble because she had promised to do a translation of Arunachala Puranam for me while she was here. This is a Tamil work that records most of the stories that appear in the Arunachala Mahatmyam. Everything was ready for her arrival but the Indian embassy in Paris gave her the wrong form to fill in (a tourist visa application) and when it was processed, it was turned down because one cannot do academic research in India on a tourist visa. She had to abandon all her research plans and stay in France with her husband and son. Once you have been turned down for a visa, you can’t apply again, even if it is the government’s fault for giving you the wrong form. Another resource gone.

While all this was going on, I was continuing to collect material. I had found a version of the Arunachala Mahatmyam entitled Kodi Rudra Samhita in a government manuscript library in Madras. Since it only existed on palm leaves, I had to engage a pandit to copy it out for me in the library. The only person I knew who knew enough Sanskrit to tackle this kind of job was a devotee called Jagadish Swami who lived in Ramanasramam. I gave him a xeroxed copy and he said he would have a look at it and tell me afterwards if he thought he would be able to translate it for me. Before he had a chance to go through it, he died while he was meditating in his room. He sat cross-legged on a metal chair, which must have been very uncomfortable, in the evening for his usual meditation, and was found there the next morning, still upright, and still cross-legged, but definitely dead. I suppose that it was a good way to die, but I really hoped that my manuscript didn’t have anything to do with it.

A couple of days later I did a pradakshina of Arunachala. I faced the mountain when I reached the Ganesh temple and tank that is about a third of the way round the hill.

I addressed Siva and said, ‘Too many things are going wrong with this project. If you don’t want me to carry on with it, give me a sign.’

I should mention that I had already asked Saradamma at Lakshmana Ashram if I should carry on with the work, and she had refused to commit herself either way. She told me that she didn’t want the responsibility for it. I had already told her about some of the bad things that had been happening. I should have taken this lack of enthusiasm as a sign to stop.

Anyway, within a day or so I received a bill from the man in Madras who had copied out the Kodi Rudra Samhita for me. I think I assumed at the time that this bill had been paid long before. It was a minor event, but I took this as the sign that I should stop.

Relative to the other people who were involved in this project, I escaped rather lightly. I fractured my femur around this time and spent twelve weeks in traction, but some of the others fared far worse than I did.

Some of the work I did on Arunachala saints did eventually appear in The Mountain Path, the ashram’s magazine, but not under my name. I was already contributing articles on Bhagavan under my own name, so when I had other material to contribute I would usually use someone else’s name. One man, for example, had managed to get a study visa to come to India, but he wasn’t doing any studying. He was just meditating instead. I put a couple of articles in his name so that he would have something to show the police if he ever got the midnight knock. Another friend of mine, Nadhia Sutara, was staying at Guhai Namasivaya Temple on the hill. Since her tenure there was not very secure, I put her name on two articles about Guhai Namasivaya and Guru Namasivaya, hoping that the man who ran the place would be impressed enough to let her continue to stay there.

Michelle: Amazing! You are lucky to still be alive. What did you turn to after this project fell through?

David: I started to collect the reminiscences of old devotees of Ramana Maharshi, particularly the ones that hadn’t appeared in English before. I think the aim was to produce a large, single-volume anthology in which each devotee would be given a chapter to tell his or her story. I collected a lot of good material, but the book itself didn’t see the light of day until fairly recently. It got demoted in my priorities because other projects came up that seemed more exciting, more appealing.

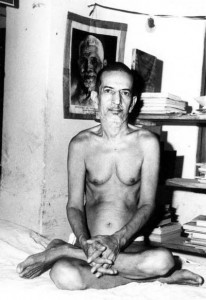

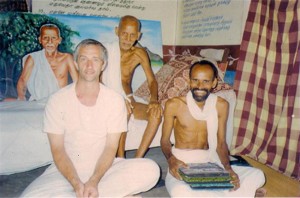

Around 1987 I approached Annamalai Swami and asked him if I could interview him for this book. I knew he had worked with Bhagavan in the ashram in the 1930s and I assumed that his reminiscences would probably make a good chapter. Annamalai Swami’s translator, who was a good friend of mine, lobbied on my behalf but couldn’t get Annamalai Swami to agree to talk to me. Several weeks went by during which Annamalai Swami steadfastly refused to tell me his story. Then Sundaram, his translator, had a flash of inspiration.

He told Annamalai Swami, ‘David has already written a good book on Bhagavan’s teachings. Many of the foreigners who come here say that it is the best book on Bhagavan’s teachings.’

This intrigued Annamalai Swami because he himself spent an hour or so every afternoon answering questions on Bhagavan and his teachings. He was beginning to attract foreign visitors to his ashram, and he agreed to talk to them on condition that the sole topic of conversation was Bhagavan. He didn’t want to talk about anything else. Bhagavan had told him not to socialise and to stay at home and meditate as much as possible. People who just wanted to meditate with him were told to go and meditate in Ramanasramam, but people who had questions about spiritual practice, or Bhagavan’s teachings were generally welcome, but only for as long as it took for Annamalai Swami to answer their questions. He was a hard man to get to see, and it was even harder to get to spend a lot of time with him.

Annamalai Swami instructed Sundaram to get hold of a copy of Be As You Are and read it out to him. Annamalai Swami didn’t know much English, so Sundaram had to translate as he went along. Annamalai Swami listened to almost the entire book before finally deciding that he would be willing to talk to me.

When I finally managed to see him, he told me, ‘You have a good understanding of Bhagavan’s teachings. I know that if I speak to you, you will not misrepresent what I say.’

There was already a very bad book about his life in Tamil by Suddhananada Bharati, and Annamalai Swami didn’t want another equally bad version to appear.

Up until that time Annamalai Swami had not told his story to anyone, or rather I should say that he had not told his story in a systematic way. He had told Sundaram and a few other people odd stories, but he had never linked them all together. For the next few weeks I went there every afternoon and interviewed him for about ninety minutes. I soon realised that this was not going to be just another chapter in my book. The material he was giving me was so astonishing, so extensive, I knew I had a full-length book project on my hands. When the interviews were completed, it took me almost eighteen months of steady, patient work and detailed research to put together the book Living by the Words of Bhagavan.

Annamalai Swami was something of an inspiration for me. He seemed to epitomise and embody all the qualities that a good devotee needs when he is dealing with his Guru and his ashram. I admired his integrity and his unshakable determination to carry out Bhagavan’s instructions, irrespective of the consequences. That’s why I called the book Living by the Words of Bhagavan. Annamalai Swami’s whole life was dedicated to carrying out his Guru’s words.

When Sundaram read out the final version, Annamalai Swami was very happy with it. However, when he arranged a second reading for the Tamil devotees who couldn’t understand the original English, some of them pointed out to him that a few of the stories might get him into trouble with the Ramanasramam authorities. He agreed that this was probably true. He sent for me and told me to hide the manuscript and not let anyone see it.

‘When I am dead,’ he said, ‘you can do anything you like with it, but until then don’t let anyone read it. Bhagavan told me to lead a quiet life and not to see many people. I will not be able to follow his instructions if lots of people come to see me as a result of reading this book, and I don’t want my life to be disturbed by people coming here to complain about some of these stories.’

This was 1987 I think. I put it away and didn’t take it out again until 1994. That year, he changed his mind and allowed it to be printed. A year later he passed away. I think he was right to put off the publication. When it came out, it did attract a lot of new people, and several of them did come to complain about some of the stories he had narrated.

In the last few months of his life there was a tape recorder running while he gave his answers to visitors. At Sundaram’s request I edited these new dialogues into a new book, Final Talks, which, I think, makes quite a nice supplement to the original biography.

Michelle: We seem to have filled in some of the blanks on your 1980s map. What were you doing for the rest of the time?

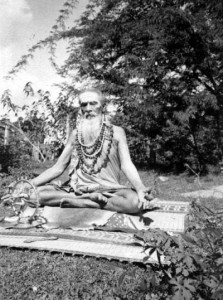

David: While I was collecting more information about old devotees of Bhagavan and from about 1988 onwards, I was also helping Lakshmana Swamy and Saradamma with a piece of land they had bought here.

Lakshmana Swamy had mentioned a few times that he wanted to move back to Tiruvannamalai. Sundaram, Annamalai Swami’s translator, and I were asked to look for possible properties that might be suitable for him. We found a few, but every time Lakshmana Swamy was taken to see them, they didn’t appeal to him. At one point we actually agreed to buy a piece of land near the junction of the pradakshina road and the Bangalore road, but the owners backed out after a price had been agreed.

Then a piece of land came on the market that was located behind the Government Arts College. Much to our surprise Lakshmana Swamy gave the order to buy before he had even seen it. It seems that he had been sitting on this land in the early 1950s when he had suddenly had a vision of himself living there forty years later. The next time he came to Tiruvannamalai he looked at the land and confirmed that this was the place where he had had the vision. He had let us run around, looking at other properties and negotiating for them, but somehow he seemed to know that he would end up living in the place where he is now.