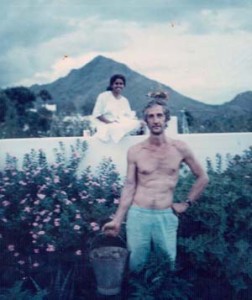

I volunteered to develop the garden. It was just an empty field when we started, so empty in fact that we had to get the government surveyor in to determine where our piece of empty field ended and the neighbours’ empty fields began.

We surveyed the land, fenced it, dug a well and started a nursery of trees. The well didn’t produce any water, so we ended up running a pipe to a neighbour’s well and buying from him. For about three years I put in several hours a day in this garden, growing trees and flowers. It was a tough time to start a project like this because there was a drought in the area. The monsoon failed several years in a row. A house was started for Lakshmana Swamy and Saradamma, but work was halted when the water ran out. We could have shipped water in tankers, but we discovered that it was too saline to be used in building work. The water would have corroded the steel inside the cement. When the work stopped, I ended up being the night watchman there. The house was full of tools and cement bags, but there were no doors and windows to protect them. I think I slept on this building site for most of a year, watching the property and waiting for the rains to come so that the work could continue. For two summers in a row I bought water in tankers to keep the garden alive. Every well in the neighbourhood was completely dry.

I was still living in Ramanasramam, working on my project to collect and edit the stories of Ramana devotees. Sometime in 1990 I wrote to Papaji in Lucknow, asking him if he would be willing to contribute his story to the book. He wrote back, saying that he would be happy to have his story included, but he added that he didn’t want to write it down himself. He asked me to submit a questionnaire, and he would then do his best to answer it by giving verbal answers that would be recorded on tape. This seemed like a good suggestion.

It took him a few months to get round to it, but when he finally did, he spent at least an hour talking about his early life and his association with Bhagavan. There seemed to be a few major discrepancies in his account, but when I wrote, asking for clarification, he just repeated the same stories all over again. In 1992 I decided to go and see him in the hope of getting his story straightened out. I spent a chaotic two weeks with him, chaotic because his wife died about three days after I arrived, which meant a major disruption to his usual routine. His family descended en masse; there was a trip to Hardwar to immerse the ashes in the Ganga; but in between all these comings and goings I managed to get most of the information I had been looking for. A lot of it came in a last-minute interview I had with him about an hour before my train was due to leave. It was that kind of trip.

Back in Tiruvannamalai I went through all my notes and put together a fifty-page version of his life that focused on his early life and the meetings he had had with Bhagavan. At the time I wasn’t interested in anything that came after 1950. I submitted it with some hesitancy because there were still a few events that I couldn’t place in the right order, but he seemed to love it. He invited me back to Lucknow, telling me that he had many more stories he wanted to tell me. I went back in March 1993, intending to stay for a short time, but I ended up staying there until he passed away in 1997.

Michelle: What was the attraction? What made you decide to stay, and stay so long?

David: First of all, I felt his power and I felt his peace. Here was a man who had attained liberation through Bhagavan’s grace. He was promulgating his Master’s teachings and radiating a kind of tangible sakti that shut up the minds of the people around him, and in some cases gave them temporary experiences of the Self. It was a heady, intoxicating environment in which people were having amazing experiences almost every day. On top of that there was the promise of getting more extraordinary stories from him. My first trip there had been a kind of smash-and-grab raid. I had come with very limited time. With all the funeral events going on I had had to remind him constantly that our time was limited and that I wanted to talk to him about his life. Second time round I waited for him to take the initiative, but strangely enough he didn’t. Having invited me there to record his stories, he never showed any interest in telling them.

Within two weeks of my arrival I was given a book project that someone else couldn’t deal with. A German doctor, Gabi, had been asked to collect interviews that Papaji had had with various visitors and arrange them in book form. She was struggling a bit with this because she wasn’t a native English speaker. I was asked to help her, and when she left Lucknow a few weeks later, I inherited the whole project. I wanted to take my time and do it properly, but Papaji wanted it to be brought out in a hurry. He didn’t seem to have much patience with long, drawn-out projects. His motto seemed to be ‘Do it, and do it now!’

One other reason for the slowness was that Papaji also got me involved in a film project. An American film-maker, Jim Lemkin, arrived in Lucknow and asked if he could make a documentary about Papaji and his teachings. Papaji agreed and sent me along as a kind of advisor, interviewer and general consultant. I don’t know why I got this job. I had never worked on a film before in my life. Within about three months we had the film ready. I had spent my first three months in Lucknow finishing somebody else’s book and helping Jim with his film. There was no sign, however, that Papaji was willing to start talking about any of the incidents he had promised to tell me. I dropped several hints, but no business resulted.

After a few months I suggested that he could just sit in front of a camera and tell all the main stories of his life. I didn’t know what else to do to start him talking.

‘I couldn’t do that,’ he replied. ‘I would need some notes to remind me which stories I wanted to tell.’

This sounded like another excuse to put off the answering, so I decided to push the issue a little.

‘No problem,’ I said. ‘I’ll make the notes for you. I’ll make a list of every story I have ever heard you tell, and every incident I have heard about your life, and I will arrange them in chronological order. You can go through the list one by one and answer any that appeal to you.’

I got no answer to that one, but I went ahead and made the list anyway. I gave it to him one afternoon while he was having his afternoon tea. He seemed to be very excited by the first few questions, saying what good questions they were, and how much he would enjoy talking about them. Then he turned the page and realised that it wasn’t two pages he had to go through. It was sixteen.

His face dropped and his enthusiasm vanished. ‘This is a very long list,’ he said, all excitement gone.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘you have had a very long life, and it has been full of interesting incidents.’

I was hoping I hadn’t blown my chance by overloading him with questions.

‘I’ll have to go through it,’ he said. ‘I’ll make notes in the margins about what I want to talk about.’

That seemed to be good news. At least he was going to try.

The list of questions stayed in his bedroom for several months, completely unread so far as I could ascertain. I would occasionally mention it to him and he would reply that he was working on it. Whatever he was doing, he wasn’t doing it with the papers in his hand.

In 1994 I received news that Annamalai Swami wanted me to print his book. I approached Papaji and asked him what I should concentrate on. I should mention at this point that I had unofficially inherited another project that was known as the ‘Om Shanti’ book. In 1992 and early 1993 Papaji began his daily satsangs with a brief talk on whatever he felt inspired to speak about that day. These had been transcribed and there was a plan to make a book of them. At one point Catherine Ingram was supposed to be doing this, but when she wrote to Papaji, saying that she couldn’t do it, she added ‘Maybe David can do it instead’.

Papaji read out the letter and said, ‘Yes, David can do it’. I was sitting in a far corner of the room at the time, but he never looked at me, and he never officially asked me to start the work. Since I didn’t particularly want the job – I had enough on my plate already – I never asked him about it myself until this meeting I had with him in 1994.

I explained to him, ‘I have been asked to go to Tamil Nadu to make sure this Annamalai Swami book gets printed properly. You said indirectly that you wanted me to edit this ‘Om Shanti’ book, and the questions about your biography are all still pending. What do you want me to do, and in what order?’

‘How near is the “Om Shanti” book to completion?’ he asked.

‘There’s one version available,’ I answered, ‘but no one likes it. If I took up that work, I would probably have to start from scratch and do it all again. It would probably take several months.’

‘OK,’ he said. ‘we don’t want that project any more. It’s not necessary. Go back to Tiruvannamalai, print your new book, and when you come back we will start on my biography.’

This was just what I wanted to hear. I had permission to go away and print Annamalai Swami’s book; I had got myself out of a job that I didn’t really want to do; and I had received a promise that he would start work on my main project as soon as I returned from the south.

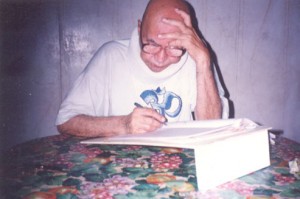

That’s not what happened though. Things rarely go according to plan when Papaji is concerned. As soon as I left the house to go to South India, he sent someone out to buy a big foolscap notebook. He took my questionnaire from his bedroom, blew the dust off it, and began to answer all the questions by writing them out in this book. The people who were there said he spent several hours a day patiently going through all my sixteen pages of questions. It must have been very uncomfortable for him. It was summer, there were frequent power cuts, and he had a brace on his neck because he was suffering from spondylitis. That made it hard for him to look down and see the page he was writing on. He stuck at it, though, day after day, and when I finally returned he had written almost 150 pages. The moment I walked into the house, he put his pen down and wouldn’t write any more. I have thought about this many times, but I still can’t come up with any sensible conjectures. Why did he have to wait half a year until I was out of town to start writing his memoirs, and why did he stop the moment I returned? He had asked me to be his official biographer, but he seemed to be incapable of answering questions when I was around. I should add that no one would ever accuse him of being shy or diffident. If he wanted to do something, he did it, and if he wanted to say something, no social convention on politeness would prevent him from saying exactly what he wanted to say. He was a bulldozer in everything he did.

These handwritten stories were just what I needed to start my book. There were many incidents I had never heard before, along with good versions of stories that I already knew. I got myself organised. I found myself a computer; I recruited volunteers who were willing to listen to all the old satsang tapes in order to find all the different versions of the stories he told; I started collecting letters from all the people he had written to over the years; I wrote to everyone whose address appeared in his address book; and I started interviewing everyone I knew who had been connected with him. It was a long, long job, but it was immensely rewarding. I discovered many people from all over the world who had been utterly transformed by Papaji, sometimes after only a single meeting with him. Whenever I needed supplementary information, I would write out a list of questions, and he would give me written answers. He seemed to prefer this format when he dealt with matters pertaining to his life story. However, whenever I asked him questions about his teachings, he would take the list to satsang and give answers there so that everyone could immediately benefit from what he had to say.

For most of his life Papaji forbade his devotees from talking about him. He wanted a high level of secrecy to guard his privacy. When I started writing to old devotees, asking for their stories, they immediately wrote back to Papaji, asking what they should do. I had told them all in my letters that I was doing this with Papaji’s permission, but, quite rightly, they all felt a need to check. Papaji encouraged and in some cases even ordered these people to tell me their stories. Some people told me about incidents they hadn’t even mentioned to members of their own families.