Every time I finished a chapter, I would give it to Papaji to read and check. At first he would go through it in his house and then later take it to the morning satsang and read it out there. Later, though, he would just say, ‘Put it in the satsang bag. I’ll read it tomorrow.’ I have to say that I was touched by the faith he showed on these occasions. I don’t think I would volunteer to read out a biography of myself in front of 200 people without first checking to see what was in it. In the beginning he would make a few corrections, but once I got the hang of how he liked to have his stories presented, he rarely touched any of them. He even stopped reading with a pen in his hand. In the last few hundred pages the only things he changed were the spellings of the names of a few Indian devotees that I had misspelled because I had never seen them written down before. He finished the last portion about a month before he passed away in 1997. Sometimes I wish that I had worked a bit harder so that I could have presented him with a copy of the first book, but that wasn’t ready until the middle of 1998.

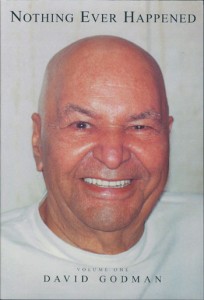

After Papaji passed away in September 1997, I finished work on Nothing Ever Happened and came back to Tiruvannamalai, and I have been here more or less ever since.

Michelle: What work did you start when you came back here? What are you working on now?

David: I did nothing for a while. I took a break from writing. I didn’t feel like doing anything new. Until the middle of 1998 there were proofs of Nothing Ever Happened to go through, but after that I had a complete break from book work for about a year. Papaji had asked me to edit his Lucknow satsangs for him and bring them out in book form. He even told me what format to use. That’s a big job and I have only just started on it.

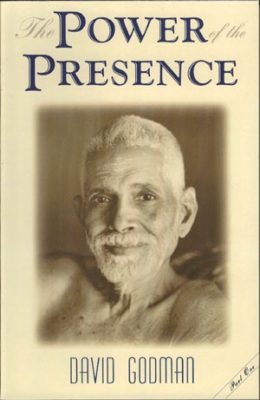

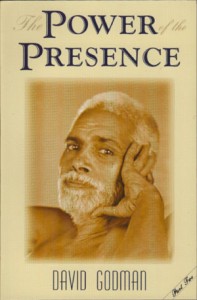

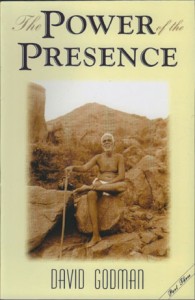

In 1999 I suddenly remembered the reminiscences project I had started in the 1980s. Two books on Annamalai Swami and four books on Papaji had sidetracked me for a decade, but when one of my friends here asked to have a look at one of the unpublished chapters, I took everything out of its folder and read it for the first time in maybe ten years. Realising that I still had plenty of good material that deserved to be printed, I started to organise it into book form. That particular project, The Power of the Presence in three volumes, started about two years ago and ended quite recently when I finally received the last volume from the press.

Michelle: You are now publishing your own books. What made you take that decision?

David: In the middle of 2000 I approached Penguin in Delhi to see if they would be interested in bringing out the series that later came out as The Power of the Presence. I also wanted to see if they might be willing to bring out an Indian edition of Nothing Ever Happened since it is far too expensive for most Indians to buy. Right now, only the American edition exists. Its $45 price translates as over Rs 2,100 in this country. Hardly anyone can afford that kind of price here.

When I went to see the commissioning editor for spiritual books in the headquarters of Penguin India in Delhi, the woman I spoke to claimed that Be As You Are was not a Penguin book, and that the office had no record of either the book or me. I couldn’t believe she was serious, but she was. The book has been continuously in print in its Indian Penguin edition for more than ten years but there was no trace of it, she said, either in their catalogues or on their computers. I decided I didn’t want to deal with a company that could lose titles and authors so completely that no record of them showed up on their computers. It wasn’t just the English edition she had lost. She didn’t know anything about the versions that had been brought out in several Indian languages.

I have always had bad experiences with commercial publishers. When Be As You Are first came out in the mid-80s, the original publisher didn’t tell me it was out, and didn’t even send me a copy. The first copy I ever saw came from a friend of mine who bought it in a second-hand bookstore.

I decided in the end to publish The Power of the Presence myself. I find it quite rewarding to be involved in everything from the original idea to distribution and marketing points several thousand miles away.

Michelle: Other than the new Papaji books, is there anything else in the pipeline?

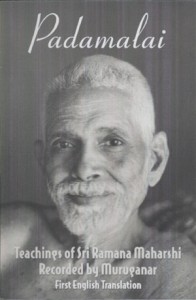

David: I am working on a new presentation of Bhagavan’s teachings that I hope will come out around the end of the year. It will be based on teaching statements by Bhagavan that were recorded by Muruganar in a Tamil work entitled Padamalai. That will probably be the title of the book when it comes out. There are also a few other possibilities, but they are so vague, I don’t really want to start talking about them. I think I have said enough for one afternoon. I haven’t talked this much for months and I think my voice is going. Come back in a year and ask me ‘What’s new?’ and I might have something more to tell you. That’s enough for now…

[This is where the 2002 interview ended. The next section was written, without an interviewer, in 2014:]

David: The book I mentioned in the final paragraph of the interview, Padamalai, eventually came out in 2003. It was taken from a Tamil work of the same name that was over 3,000 verses long. The original Tamil poem had no structure at all, and many of the verses were very similar insofar as they repeated the same idea in almost the same language. The work appeared in the final volume of a nine-volume series entitled Sri Ramana Jnana Bodham. It contained all the stray verses of Muruganar that had not appeared in any of Muruganar’s previous books. Muruganar was a hugely prolific and spontaneous poet who, over his lifetime, composed more than 20,000 verses on Bhagavan and his teachings. After he first came to Bhagavan in 1923, he took a vow that he would not compose poetry on any other topic, a decision he adhered to for the rest of his life.

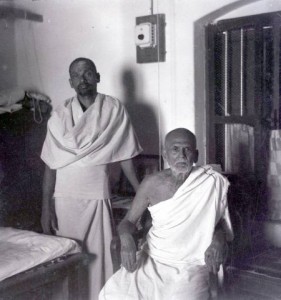

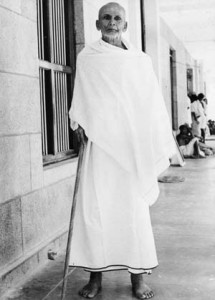

Muruganar had appointed Sadhu Om to be his literary executor and bequeathed all his papers to him. In his final days (early 1970s) Muruganar was staying in the room next to the Ramanasramam dispensary. The ashram management wanted to take charge of all his papers, but Muruganar knew that there was no one other than Sadhu Om who had both the knowledge of Tamil literature and the commitment to preserve the papers. He gave the ashram an ultimatum, saying that if he was not allowed to pass on the manuscripts to Sadhu Om, he would burn them all because there was no one else he trusted to bring them out properly. The ashram backed down and allowed Sadhu Om to collect all the manuscripts. Sadhu Om spent the following twelve years organising the manuscripts and publishing the previously unpublished verses.

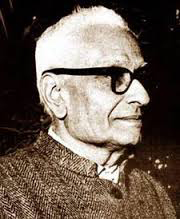

Professor K. Swaminathan , who was working for the Central Government in New Delhi as the Chief Editor of Gandhi’s Collected Works, was a great lover of Muruganar’s poetry. He persuaded the government in New Delhi to give a grant to the New Delhi Ramana Kendra that would enable it to publish all the remaining unpublished poetry of Muruganar. Nine Tamil volumes of Sri Ramana Jnana Bodham were eventually published. They went on sale at the highly subsidised price of Rs 10 per volume. Sadhu Om passed away before the series was completed, but the people who had helped him to work on the project continued the editing work until all nine volumes had been published. Volume nine did not appear in Tamil until the late 1990s, more than twenty-five years after Muruganar’s passing.

Around 2000 or 2001 T. V. Venkatasubramanian, who had helped me with translations for The Power of the Presence, mentioned that the final volume of Sri Ramana Jnana Bodham contained this long 3,000-verse work, Padamalai. Though some of the verses contained statements by Muruganar either praising Bhagavan or expressing gratitude, the majority of them contained a teaching statement made by Bhagavan himself. This, for me, was like stumbling across buried treasure. I had long since assumed that all the teaching material that could be sourced to Bhagavan had been published and translated, and that nothing else remained. I was therefore delighted when Venkatasubramanian suggested that we work together on a translation of this new material.

The first decision we took was to edit out all the extra verses that simply restated ideas that had appeared in earlier verses of the same work. We also left out a few where the Tamil was so ambiguous or obscure that we couldn’t, with any authority, determine what was actually being said. Muruganar’s Tamil is dense and complicated, and even Sadhu Om occasionally had to consult him, while he was still alive, on the meaning of some of his verses. On one occasion he took a verse to Muruganar in order to get a definitive explanation of its meaning. Muruganar started at it for a few seconds before even he had to admit that it made no sense to him.

‘One day,’ he apparently said, ‘Bhagavan will reveal to us the meaning of this verse.’

This may sound odd, but it should be remembered that Muruganar’s verses came to him spontaneously. On occasions they appeared to form themselves ready-made in his head, without much conscious thinking. If he had a pen handy, he would scribble them down on a piece of paper and then forget about them. In later years he would write them out on a slate with a piece of chalk. If no one was around to copy the verse onto a piece of paper, he would frequently wipe out whatever was on the slate to record the next new verse that appeared in his mind. When this happened the old verse would be lost forever. Since he did not think much about the meaning of what he was writing, it is not surprising that, years later, he was as mystified by their impenetrability as those devotees who were asking him for explanations of them.

Having removed all the duplicate material and discarded those verses that we were too uncertain of to make any confident translation, we found ourselves with about 1,800 verses. We took a decision that we would bring them out in thematic groups, with separate chapters devoted to different topics. We also decided to add a large number of supplementary quotations from other books of Bhagavan’s teachings since the same ideas appear repeatedly throughout the teaching literature. Sometimes, for example, a paragraph in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi would expand on and explain a brief two-line verse that Muruganar had recorded in Padamalai.

After we had been working on this project for a month or so, Venkatasubramanian suggested that we get Robert Butler to help us. Robert no longer lived in Tiruvannamalai, having gone back to the UK in the mid-1980s to look after his ailing parents. He married there and acquired a large group of dependents: a wife, her three children from a previous marriage, and two elderly parents who discovered that the pension they thought they would be getting didn’t actually exist. Robert shelved his plans to come back to India and spent many years looking after his extended family.

In the early 1980s he had come to Ramanasramam where he helped me to run the ashram library.

I soon discovered that he had a natural flair for languages. About two weeks after he had announced that he was going to learn Tamil, I spotted him reading a Tamil newspaper in one of our local tea shops. It only took a few more weeks before he was immersing himself in the intricacies of literary Tamil. He was making his first tentative translations of Tamil poems about six months after he started his studies.

He returned to the UK in 1983 and continued his Tamil studies there. About a year later, while he was working as a night guard in a factory, he managed to translate a medieval biography of Manikkavachagar in between patrols of the factory grounds. In the 1990s, while he was working as a computer expert for the government of his local area, the Ramana Maharshi Centre for Learning in Bangalore invited him to make a translation of a book of Muruganar’s devotional poetry. Though he struggled with some of the verses and sought aid from various experts in India, he still managed to produce a publishable translation of the text. Many years later, when his translation skills and his knowledge of Muruganar’s style had massively increased, he revised and expanded the text and republished it himself.

When Venkatasubramanian suggested that I invite him to help, Robert had not been in India for many years. I realised that it was also many years since I had communicated with him. I found his phone number by trawling through ‘directory enquiries’ in his home town and called him from a public phone box opposite the Ramanasramam gates. This was before mobile phones had gained a foothold in India. When he discovered where I was, he asked me to open the door so he could listen for a minute or so to the raucous sounds of India that swirled around the ashram gates. He was clearly missing India, and Tamil Nadu in particular. It didn’t take me long to persuade him to join our project. In fact, he was delighted to be able to find a tough challenge that would improve his already considerable knowledge of literary Tamil.

Robert had always had a flair for languages. He knew several European languages and had eventually ended up studying French for four years at Oxford University in England and the Sorbonne in Paris. He once told me that he had won a prize at university for writing the best essay of the year in medieval Provençal, although I can’t imagine that too many people entered the competition. At the end of his final year, for no reason he can remember, he found himself in Blackwell’s, the Oxford University bookstore, buying a Sanskrit dictionary, a Sanskrit grammar book and a teach-yourself-Sanskrit book. He had never been to India or felt any attraction to go, but he said something made him pick up these books, buy them, take them home and study them.

He sat down at a table, opened the books and attempted to go through the first few lessons. For no reason he could think of, he couldn’t concentrate on them. Every time he sat down, he felt physically uncomfortable and spent more time fidgeting than actually reading the books. This was the first language that he had not been able to focus on and learn quickly. Eventually, after a few days of what appeared to be a half-hearted attempt to pick up the basics, he gave up, deciding that this was one language he was not destined to learn. A couple of weeks later, while he was sitting cross-legged on the floor, he decided to have another go. This time the learning was effortless, and he picked up Sanskrit as easily as he had all his other languages. He used to joke that his Sanskrit samskaras (habits and tendencies from his past lives) were stored in his knees, and that once he assumed the right position, the language he had learned before flowed effortlessly back into him. He was, most definitely, an Indian pandit in exile. During the 1980s I used to send him dhotis by post from India. He hated wearing trousers but had to put up with them during his day job with the government. In the evening, though, he would put on a dhoti, sit cross-legged on the floor and study Tamil poetry.

Over the years he developed a passion for Sangam poetry, a mysterious era of Tamil literature from about 2,000 years ago. He learned the intricacies of its style, symbolism and grammar and was eventually good enough to publish a translation of Kuruntogai, one of the major collections of love poetry from this neglected period of Tamil history.

The leader of our translation team was T. V. Venkatasubramanian, a Tamil brahmin who followed up a Ph.D. in metallurgy in Chennai with a seven-year period of post-doctoral work at London University. Though he loved his scientific work and probably would have reached the top of his profession, had he stayed in academia, his principal passion was Bhagavan, and in particular the Tamil writings that recorded his teachings. He retired while he was still in his thirties, bought land on the pradakshina road, and built a house for himself there. He would do a pradakshina of the Arunachala every morning and then devote much of the rest of the day to learning literary Tamil and studying the spiritual classics that have been composed in that language.

I have not included any photos of Venkatasubramanian because he is a reclusive man who doesn’t like to have a public profile. I doubt if many people, outside of a few people at Ramanasramam who collaborate with him on literary projects, would even recognise him if they passed him on the street. I think he likes his anonymity and guards his privacy, so I won’t intrude on it by posting any photos.