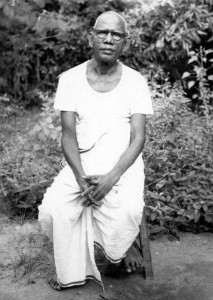

The grammar of literary poetic Tamil is different from that which is spoken conversationally, so much so that educated Tamils cannot read their own classic literary texts unless they have undergone an extensive period of training in the rules and conventions of Tamil prosody. Venkatasubramanian applied his scientific intellect to this job. Within a few years, with almost no help from any teacher, his knowledge of literary Tamil was second to none. He had an almost photographic memory that allowed him to remember almost everything he had ever read or studied. He thought this was a product of the Indian educational system that generally taught students by rote learning, but I think there was more to it than that. I think he was naturally blessed without an almost perfect recall of every text he had ever gone though.

Venkatasubramanian had a strong interest in the Tevarams, the Tamil devotional hymns that were composed over a thousand years ago by three Tamil saints, but when he moved to Tiruvannamalai he turned his energies to the works of Muruganar, the poet-devotee of Bhagavan who composed over 20,000 verses that praised his master or recorded his teachings. Venkatasubramanian had helped me with several chapters that went into The Power of the Presence. When that work was complete, he suggested that we turn our attention to the works of Muruganar. I agreed, and we began a fruitful collaboration that has so far lasted over thirteen years.

Robert’s translation style was stunningly poetic, whereas Venkatasubramanian tended towards the literal and the prosaic. His mindset, possibly a result of his scientific training, had a zero tolerance for error. He wanted the meaning to be exact and perfect, even if the phrasing ended up being a little clunky in places.

Our translation work would start in Venkatasubramanian’s house on the pradakshina road. Though he had a Ph.D in science, he had no interest in computers. We would sit cross-legged on his floor, pen and paper in hand, and slowly work our way (often syllable by syllable) through whatever verses we had selected for that day. If the translation was fairly easy, he would usually make a draft that we could then work on together for an hour or so. Once he was satisfied that he had explained all the nuances of meaning, of what qualified what, and how the multiple clauses should be lined up, I would go home and spend an hour or two trying to create a more elegant version, without compromising the integrity of the translation. I would generally show him my version the next day. Invariably he would decide that it needed further work, further tinkering, in order to reflect more accurately the precise meaning of the original Tamil. Once we had arrived at a version that satisfied both his penchant for literalness and my strong desire for elegance and readability, I would email our version to Robert, often with copious notes that explained how we had arrived at our final version. Most days we would ask his advice on sentences that, despite our best efforts, we could not render into elegant English. Robert would often rewrite what we had done, and while his versions were invariably in better, more flowing, English, Venkatasubramanian would often dig in his heels and declare that he had deviated too far from the original Tamil grammar. Versions would go backwards and forwards multiple times until all three of us were happy to sign off on a final version.

Though the three of us have worked on four books together, along with a significant number of smaller projects, it is a peculiarity of our working relationship that we have never once sat down together and jointly worked on a text in the same room. Robert contributed his work by email from England; I worked with Venkatasubramanian in Tiruvannamalai and acted as the general liaison between them. The creative and stimulating tug of war between Venkatasubramanian’s literalness and Robert’ stylistic flair was a long-distance affair that often ended up with me drafting compromise versions that satisfied all three of us.

Around 2001 Venkatasubramanian decided to translate Sri Ramana Darsanam, a Tamil work that had been written in the 1950s by Sadhu Natanananda, a scholarly devotee of Bhagavan who had first seen Bhagavan at Skandashram in 1917.

Natanananda went on to compile Upadesa Manjari (Spiritual Instruction), a series of questions and answers that impressed Bhagavan so much, it was included in the Tamil edition of Collected Works. In subsequent years Natanananda edited the question-and-answer version of Vichara Sangraham (Self Enquiry) and wrote the essay version himself. This text has also appeared in all the editions of Collected Works that have appeared since Natanananda made his initial version of Vichara Sangraham in the early 1930s. In 1939 Bhagavan asked him to be the editor of Guru Vachaka Kovai, a collection of his spoken teachings that had been recorded by Muruganar. I will revert to that later since it is one of the texts that Robert, Venkatasubramanian and I translated together.

Sadhu Natananananda’s style was dense, literary and in places unnecessarily prolix. He could write sentences that went on for several pages, and within those sentences there might be several subsidiary topics that seemed to have little or nothing to do with the general argument he was trying to make. He loved footnotes, so much so he would occasionally have footnotes on his footnotes. His writing style was so ornate, literary and densely philosophical, ordinary Tamils would have had very little chance of understanding what he was trying to say. I showed an early draft of our translation to Sundaram, the President of Ramanasramam, since the ashram had promised to publish the book. He returned it the next day, praising it effusively.

‘I knew it would be a good book!’ he exclaimed. ‘But I didn’t realise how good it would be.’

‘Haven’t you read the original?’ I asked, somewhat innocently.

‘Of course not,’ he replied. ‘No one reads Natanananda in the original Tamil. We can’t understand a word he is saying.’

That was from a native Tamilian, a man who knew Natanananda personally, and who enjoyed reading Ramana literature.

The impenetrable nature of the original text was something we had to address in the translation. We wanted to make the English version demonstrate the denseness of the original, with its interminable sub-clauses, but we didn’t want it to be as inaccessible as the Tamil edition. We therefore split up most of his never-ending sentences into smaller units, but tried to keep the magisterial nature of some of the statements he had Bhagavan say. This, for example, is Natanananda having Bhagavan explain that touching the Self inside oneself was the true meaning of touching the Guru’s physical feet:

Only the Supreme Self, which is ever shining in your Heart as the reality, is the Sadguru. The pure awareness, which is shining as the inward illumination ‘I’, is his gracious feet. The contact with these [inner holy feet] alone can give you true redemption. Joining the eye of reflected consciousness [chitabhasa], which is your sense of individuality [jiva bodha], to those holy feet, which are the real consciousness, is the union of the feet and the head that is the real significance of the word ‘asi’. As these inner holy feet can be held naturally and unceasingly, hereafter, with an inward-turned mind, cling to that inner awareness that is your own real nature. This alone is the proper way for the removal of bondage and the attainment of the supreme truth.

I seem to recollect that this was all one sentence in the original. The word ‘asi’ that appears in the quotation refers to the mahavakya ‘tat tvam asi’ (you are that). Asi means ‘are’. Bhagavan’s metaphor indicates that the inner state of being is revealed when individuality is merged in the ‘holy feet’ of pure consciousness.

It was not all as dense as this. There were many entertaining anecdotes, along with a serious analysis of many aspects of Bhagavan’s teachings.

I liked Natanananda’s approach to Bhagavan’s teachings because it was always anchored in the advaitic reality of Bhagavan’s own experience of the Self. All the teachings, all the quotations and all the anecdotes led back inexorably to the formless Self that can only be found by contacting the Self within.

A German friend of mine who read the manuscript before it was published told me, ‘I like the way this man writes. He doesn’t spread too much butter on the bread.’

That’s Natanananda in a nutshell: an austere, scholar-philosopher who was always encouraging his readers to stick to the essentials and not get caught up in anything in Bhagavan’s life and teachings that was peripheral to the essential core teachings.

However, don’t get the impression that he was merely a dry, dusty academic whose knowledge was only intellectual. He experienced the truth of Bhagavan’s teachings and disseminated them from direct experience, not from knowledge acquired by studying them. At the end of Sri Ramana Darsanam we added two long poems by Natanananda that had not appeared in the Tamil original. Though they mostly summarised Bhagavan’s teachings, there were occasional glimpses of the experience that Natanananda had attained through his practice and through Bhagavan’s grace. Here are a few samples:

I rid myself of burdens by surrendering my life to the guardianship of Sri Ramana. Responsibility for my life became his, and I attained salvation.

When I realised that no actions were ‘my’ actions, and that all actions were actions of the Lord, I was freed from ego.

Only the thought of Siva Ramana made my mind clear, dispelling completely the fear of birth and death.

By getting rid of oppressive attachments, ‘I’ died. What is now animating the body is being-consciousness, that which abides as my Lord.

What excellent deeds did I, a dog, perform in the past that enabled me to come into contact with him who has no equal, and by doing so attain salvation?

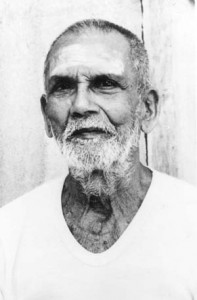

Sadhu Natanananda was my neighbor when I first lived in Tiruvannamalai in the 1970s. I would pass him on the road occasionally as we walked to and from our respective houses, but we would never even greet each other. I was told by an old devotee of Bhagavan, Viswanatha Swami, that he didn’t like people noticing him or saying ‘hello’ to him on the street. Viswanatha Swami had actually written an introduction to the first Tamil edition of Sri Ramana Darsanam in the 1950s, but I noticed that even he looked at the ground when Natanananda passed by. Natanananda was a simple, humble man who liked to mind his own business, without being publicly bothered by anyone when he went out.

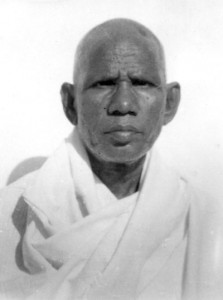

Viswanatha Swami made the following telling remarks about Sadhu Natanananda in his introduction:

Having such a subtle understanding, Sadhu Natanananda followed the path of Sri Bhagavan’s teachings, ultimately becoming one who attained the true benefit of them…. Through his book Sadhu Natanananda enables all of us to have the darshan of the true nature and form of Sri Ramana Bhagavan, having himself seen it and been redeemed by it.

When Venkatasubramanian and I had finished our work on the book, I handed over the file to the President of Sri Ramanasramam and forgot all about. It was ready for the press, and I think I expected to see a copy of the book in a few weeks’ time. Unfortunately, there was an unforeseen drama that had to be negotiated first. I happened to be in the ashram office a couple of months after I had handed in the file. I saw, lying on a table, a copy of our translation that had been printed out and circulated. Several people had decided that it needing editing, and each in turn had scribbled changes all over the manuscript. I noted from the print out that many parts of our text had been changed, and that these changes had already been incorporated in the most recent print out I was looking at. Unfortunately, the anonymous editors had not been consistent or thorough. For example, someone had changed ‘jiva’ to ‘jeeva’ in a few places, but ignored the occurrences in the rest of the book. Someone else had decided that some of the footnotes were not needed and crossed them out. Unfortunately, no renumbering had taken place, so the footnote sequence might go 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, and so on. Every page seemed to have had some gratuitous rewriting or addition, many of which contained misspellings or bad grammar. The text seemed to me to have been pointlessly vandalised by unqualified editors, and it looked as if these inconsistent changes were going to appear in the printed version.

I went to see Venkatasubramanian, told him what was going on, and asked if he would be willing to come with me to the ashram President and point out what had happened to our ‘final’ version. He surprised me by saying that something that has been offered to God cannot be taken back, and that once a gift of this sort has been handed over, it is not acceptable to go back and complain about how it has been utilised. I was astonished. He was such a perfectionist and would happily spend weeks ensuring that every possible error in a book had been eradicated before it went to the press. In this case, though, cultural norms dictated that he bite the bullet and let an error-strewn version of this book, with his name on the title page, be published.