I myself did not feel bound by this cultural convention. I recollected that Bhagavan would complain about errors in ashram books. He proof-read ashram books himself and complained if factual or printing errors appeared in books about him. I decided to go to see Sundaram, the ashram President, to see if I could persuade him to abandon the version that was being circulated in the ashram office. To prepare myself for the meeting I assembled a few pages of the more egregious mistakes that had crept into the text.

As I was walking to the ashram, I saw Nanna Garu walking towards me on the other side of the road. He was a devotee of Bhagavan who had a large following in northern Andhra Pradesh. His devotees treated him as a great realised being. I had a soft spot for him because he insisted that all his followers practise self-enquiry. Most of his devotees were village women from his district, but he made no concessions to their devotional inclinations. All of them were under orders to do enquiry regularly.

Every time Nanna Garu came to Ramanasramam, he would be followed around by anything up to a hundred people. I don’t think I had ever seen him alone on the street before. We had met a few times and had had conversations about Bhagavan and his teachings, but I would not describe him as being someone I was particularly close to.

However, as soon as he saw me, he came running towards me, gave me an effusive bear hug and started calling out, ‘David Godman! David Godman! How wonderful to see you here!’

He had never behaved like this before, and I had never seen him in public in Tiruvannamalai by himself, without his entourage. The whole encounter was extremely odd.

I continued to Ramanasramam where I had decided to take my problem to Bhagavan first. I put the manuscript in front on me on the samadhi hall floor, prostrated to Bhagavan, sat down, closed my eyes and mentally narrated the various events that had led me to being there. When I opened my eyes, there was a plate of chocolate chip cookies in front on me. I looked around but no one else was there. This had never happened to me before; it was the second odd thing that happened in the space of a few minutes.

I went to the ashram office to see Sundaram, the Ramanasramam President, explained what was wrong with the print out, and showed him a few examples of how the text had been needlessly mutilated. He saw the point of what I was saying and asked me how long it would take to fix all the mistakes.

I said, ‘I don’t know. It might take a week or so because this printed version already includes changes that were not in the original. I would need to do a word-for-word comparison to the original to find out what has been changed.’

His face dropped. ‘I need a published copy of this book in a week or so. I am going to the US and I want to hand out copies to the devotees I will be meeting there.’

There was a simple solution. I told him, ‘The file I gave you a couple of months ago had no errors. It was ready for publication.’

His face brightened. ‘Really! We can use that one immediately?’

‘It’s a Word file,’ I said. ‘You will have to lay out the pages in a different programme, but if you can do that quickly enough, you can have your book in time.’

He got up, said ‘Come with me,’ and marched off to the room in the ashram where all the books were prepared.

He walked in and called out in a loud voice to all the people there, ‘Whatever you are doing, stop doing it now. Godman has a file that I want to see as a book as soon as possible. In fact, I want it done…’

He paused for a couple of seconds, thinking of a suitable deadline to give us.

‘I want it done yesterday!’ Without waiting for a response, he marched out of the room.

The people in the room stared at me, probably wondering how I had managed to fire up the President like this. I don’t think anyone had seen him behave this way before. I sat down with Siva, the ashram’s principal graphic artist and book designer, and started the work. The book is not that long, but I was still surprised that we managed to get the whole file laid out in pages, and ready to print, in about six hours. By that time it was 10 p.m. Siva stayed on to design a cover and apparently went home about midnight. The next morning I went back to check it and to write the blurb for the back cover. By mid-morning I was in a position to deliver the completed file to the President. Three days later the first copy of the book arrived in the ashram, weeks ahead of the President’s US trip.

That was a miraculously quick result. I usually spent weeks perfecting the layout of my own books, and in those days I had never encountered a printer who could deliver a book in less than two or three weeks. This was before the era of ‘print on demand’. Bringing out a book still needed several labour-intensive operations.

I have often wondered about this astonishingly speedy project. Was meeting Nanna Garu on the road and getting a huge hug some kind of blessing? In the first two decades of the twentieth century Seshadri Swami would indicate by his moods whether people going to Bhagavan to ask for things would be successful or not. He was not only able to sense the question; his positive or negative response would also indicate whether the visitors would get what they wanted from Bhagavan.

Did Nanna Garu do something like this? And what about the plate of cookies that mysteriously appeared in front of me? And what really motivated the President’s uncharacteristic gung-ho response to my request? Were they all signs from Bhagavan that he wanted the book to come out error-free and quickly? Or was it all just an odd series of coincidences that serendipitously produced the desired outcome? I have no idea.

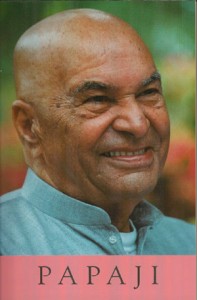

In addition to the Muruganar work, which was my main activity for much of the first decade of this century, I also managed to edit and bring out a book of Papaji’s dialogues entitled The Fire of Freedom. The origins of that project go back to an interesting encounter I had had with Papaji around 1995. There was a tradition of serving tea in his house in the afternoon. I had a standing invite to attend since I was taking all my meals there. In earlier years this would often be an intimate occasion where a small number of people would sit with Papaji at his dining room table. However, by the time this story took place, about twenty or so people would come and we would usually all sit on the floor while Papaji would sit by himself (or sometimes with one or two invited guests) at the table. I walked into his house and headed for the back corner of the room, which is where I liked to sit. Papaji called me back and asked me to sit facing him at the end of his table. No one else was asked to sit at the table, which made me feel that something unusual was going on.

After some time Prashanti walked in with some copies of , a book of dialogues with Papaji that he had compiled and published while he was on a trip to the US. Prashanti had, for many years, done all the sound recordings of Papaji’s satsangs. He had picked out the exchanges he liked, edited them, and brought them out in book form. I don’t think he had consulted Papaji about the format because Papaji immediately started to complain about the way it had been edited. The gist of his complaint was that he generally gave replies that reflected the state of mind of the people he was talking to. He might give one answer to one person on a particular topic, but if the circumstances were different, he might give a different and contradictory reply to someone else if they asked a similar question. He said that it was confusing to put replies on a particular theme on the same page, without giving the context.

He took out a sheet of paper and wrote all this down, adding that he wanted me to edit the book again and follow his guidelines. This was a bit embarrassing for me. Because I was sitting at the table when Prashanti walked in, it might have appeared to him that I had made this complaint, and that Papaji was backing me up by asking me to redo the whole book. When Papaji left, I explained to Prashanti that the scene at the table had had nothing to do with me, and that I had had no idea what was going to happen when Papaji had parked me at the end of his table. However, I had been given a job to do, and had even received a written commission for it.

I soon discovered, though, that it would not be possible to carry out Papaji’s instructions because Prashanti no longer had the notes and references that would have indicated where all the material that had been included in the book had originally come from. Without that information, it would not be possible to go back to the original dialogues and present them the way that Papaji wanted.

I went back to Papaji and explained that this crucial material was missing, and that without it, I couldn’t carry out his instruction.

He paused for a few seconds before telling me that I should start again on a new project that would consist of whole teaching dialogues.

‘Do it chronologically on a day-by-day basis. Often we talk about similar topics over several days in satsang. Or the same people come back day after day and show how their understanding or experience has changed as a result of what they have heard in satsang. None of this comes out if you mix up fragments from different dialogues on different days. When I give a reply, I am giving it to a particular person at a specific moment of time. In order for that reply to make sense, it needs a context, and the context is often what has gone on earlier in the conversation, or on a previous day. Often, even I have no idea why I say something to a particular person in satsang, but if you include whole dialogues, readers will have a better sense that teachings are being given to specific people for a specific reason.

‘You don’t have to include all the dialogues from a particular day or week. Just pick out the best ones and give them in full. That will be more useful than isolated fragments of teachings.’

As I was listening to him, I remembered that he had told me once that one of his favourite Ramana books was Day by Day with Bhagavan, a book that recorded activities and teachings in Bhagavan’s hall on a chronological basis. I got the feeling that he wanted something similar.

If you are serving a teacher and bringing out his teachings, you really should take advantage of his input to ensure that whatever you produce is accurate and in a form that he or she approves of. In the mid-1930s Ramana Maharshi was involved in a court case over the ownership of Skandashram. He had to make a deposition in front of lawyers in the hall at Ramanasramam. At one point one of the lawyers for the man who claimed that his client owned Skandashram produced a copy of Self-Realization, the first biography of Bhagavan, and asked him if he had read it before it was published. Bhagavan replied that he had not. He was then asked if it was accurate and he answered that there were some mistakes in it.

I found this to be extraordinary when I first read it. Narasimhaswami interviewed Bhagavan many times and did a lot of research to establish a narrative of Bhagavan’s early years, but it seems he never went to the trouble of showing Bhagavan his work before sending it to the press. Bhagavan never said what the ‘mistakes’ were, and now it is probably too late to find out. Bhagavan was generally happy to correct any texts that were shown to him. If Narasimhaswami had involved Bhagavan in the editing process, we might now have a far more accurate and reliable version of his life.

It may seem obvious, but I have always had the belief that, if one is writing about a teacher and that teacher is still alive, one should consult him and take his advice on how he wants his teachings to be presented. When I first started working for Papaji, he told me once, almost casually, that he didn’t like Wake Up and Roar, another collection of his teachings that had come out around the time that I had first met him. I knew he had read part one, and I also knew that the manuscript for part two had sat on a shelf in his living room unread for several months. In the end the publishers went ahead and published part two, even though Papaji had not gone through it. I wanted to find out what it was about the first book he didn’t like so that I didn’t make the same mistake myself, but I found it remarkably hard to pin him down and get a straight answer that would help me with my own work.

Finally, one day, when I wasn’t even questioning him about it, he turned to me and said, ‘That book, Wake Up and Roar, makes me sound like an American. In many places it doesn’t sound like me at all.’

That was a breakthrough. Papaji had been brought up in British India, reading and speaking British English. I decided that, even though his books were published in the US by his own foundation, I would stick to British English, British punctuation and British idioms that would not sound foreign to him.

The first job that Papaji gave me was editing the interviews that were to be published in the Papaji Interviews book. Between 1990 and 1993 Papaji had given a number of lengthy interviews to various spiritual figures, devotees and journalists, all of which had been recorded. These were very useful because Papaji adopted different ‘rules of engagement’ if it was a formal interview of this sort. In satsang, particularly in the mid-90s, if you asked a question, Papaji might simply ignore it and talk about something else, or ask you to sing a song. However, if a formal interview had been granted, the interviewer was allowed to ask about anything, and Papaji would feel obliged to address every question and give proper answers. I took advantage of this on a few occasions by asking interviewers to ask Papaji specific questions that I wanted answers to, simply because I knew he would not dodge them in the setting of a formal interview.

Papaji had selected which of these interviews he wanted to be published, and the work of editing them had fallen to a German doctor, Gabi. I was asked to help her, but when she left Lucknow, the whole project was turned over to me.

At first I was hesitant to tinker too much with his words. I would correct the grammar wherever necessary and try to keep the phrasing of the words as close to the original as possible.