Periodically I would show samples to Papaji. He would go through them, occasionally scribbling comments or corrections on the text. He didn’t seem to be particularly enthused by my offerings, but he went through them diligently.

At some point I realised that I was editing spoken comments that Papaji had made that sounded great when he uttered them, but were far less inspiring when they were recorded verbatim on a printed page. Somehow, the power that people felt while listening didn’t transfer to the written word. Just as an experiment I rewrote a few pages of one interview in my own words in an attempt to recapture some of the magic and the power of his spoken teachings. I kept all his key points and followed his arguments and logic faithfully, but I recast them in a way that, to me, read much better in print. I handed in this new sample at lunchtime and then left with some trepidation since I knew I had taken some severe liberties with his exact words.

I went back at about 4 p.m. and discovered that Papaji had gone through this new presentation in his bedroom. He was asleep when I arrived, but there was a big water melon on his table with a little flag stuck into it, on which was written ‘For David’. I knew then that he liked the new approach.

He came out a few minutes later, waving the manuscript and saying, ‘This is how I like it. Where is the rest of the book? I want to read the whole book.’

I had to tell him that the rest of the book would be some time in coming since I now had to start from scratch and convert everything into this new style.

By trial and error I had discovered that he didn’t want to sound like an American, and that he wanted me to rewrite a lot of what he had said because, like me, he seemed to recognise that verbatim transcripts were not that inspiring on a printed page. Having established a basic style based on Papaji’s own preferences, I then completed the book to his satisfaction and went on to write his biography using the same ground rules. I would rewrite just about everything, but to make sure I hadn’t overstepped too much, I would always show him what I had done and get his approval. I found a style of presentation that he liked and within a matter of days I was getting manuscripts back with no corrections marked at all.

I should like to now tell another story that indicates that Papaji did have strong views on how his teachings were being presented in public, even though he rarely made comments on this subject. I mentioned a few paragraphs back that Papaji never dodged questions or fudged answers when he was interrogated in formal interviews. Questions that would be ignored or diverted on any other occasion were dealt with head on. I remember a Dutch journalist, Sanatan, asking Papaji about the status of all the people who were teaching in his name. He specifically mentioned Gangaji, Andrew Cohen and Isaac Shapiro and wanted to know if they were merely messengers, or masters in their own right. Papaji replied that they were sent out as messengers, but their egos had come up and they now regarded themselves as gurus in their own right. He had kept quiet about this phenomenon for some time, but on this public occasion he made a very clear statement of his disapproval of their activities.

A few sentences into his answer he even remarked, ‘They are all going to hell and all their followers are going to go to hell with them.’

Papaji did tend to hyperbole on occasions, but even so this was a clear and strong statement that he very strongly disapproved of the way these people were behaving. He went on to say that he had sent these people out as ambassadors, and that the job of an ambassador is to pass on the messages from the authority that has dispatched them. The message, he said, was to encourage people to come to satsang in Lucknow. He also noted that when an ambassador exceeds his authority, he is recalled by his home government. Papaji never did contact his ambassadors directly to cancel their teaching authority, but he made it clear on this occasion that he was not happy with the way they were behaving. This, by the way, was the last public statement that Papaji ever made about his ‘messengers’. There is therefore a case for saying that this was his final word on the subject.

The interview was in January 1994. At that time I working on Papaji’s biography in Satsang Bhavan, the hall where Papaji gave satsang. Several people came up to me after this interview and asked if I could make transcripts. I thought it had been a good interview that covered many other important topics, such as the necessity of the human guru, so I made an edited version of the interview and took it to Papaji to get his approval.

I told him, ‘Several people have asked me for a transcript of that interview you gave to Sanatan. You said some controversial things in it. I just want to make sure that I have recorded and edited it properly before I pass out any copies.’

He took out his pen, went through the whole interview without making a single mark on it, and then returned it to me, saying, ‘No mistakes’.

‘So I can give away copies to anyone who wants to read it?’ I asked.

‘Why should you spend your own money on this? Make copies and sell them at the Sunday bazaar.’

In those days there was a market in Satsang Bhavan every Sunday where people who were leaving would sell household goods, and anything else they didn’t need, to people who were arriving who wanted to set up a household near Papaji. There were also a few visitors who supported themselves by making and selling various products.

The next Sunday I joined the other traders, equipped with a large stack of the interviews that Papaji had ordered me to sell. One of the first people I saw there was Isaac Shapiro, one of the teachers Papaji had singled out for criticism in his reply. He had just arrived. I decided that I should give him advance warning of what Papaji had said about him in the interview.

I went over to where he was sitting, greeted him, and said, ‘Papaji has told me to come here and sell copies of an interview he gave a few days ago. I just want to give you a heads up that he said something uncomplimentary about you in it.’

‘Oh, really?’ he said, ‘Can I have a copy?’

‘You can if you pay Rs 20,’ I said. ‘Papaji ordered me to sell them, and not to give them away.’

After he had handed over the money, I gave him a copy, showed him the page where Papaji had made his critique of all his messengers, and waited to see what his reaction would be.

He just laughed and said, ’Isn’t it great to have a master who makes jokes like this?’

Being criticised so publicly and so overtly didn’t seem to make any impression on him at all. So far as I am aware, none of the messengers ever contacted Papaji after this interview to find out why he was so annoyed with them. They just carried on doing what they had always been doing.

Books about Papaji came out that he didn’t particular like or approve of, and students of his set themselves up as teachers, many claiming to be in a lineage that went back to Ramana Maharshi. Even Papaji never claimed that he was in a lineage that had started with Ramana Maharshi. On the few occasions he spoke about the authority to teach, he said it came from the Self, not from a human authority. Apart from issuing the occasional strong disclaimer about his messengers, such as the one given in this interview, Papaji did little to bring this rather anarchic situation under control. Since it wasn’t any of my business, I just watched the show unroll around him. I decided that, since he had invited me to Lucknow to work on his biography, I would stick to that and make every effort to write and present it in a way that he would approve of. I made a point of showing him every word that I wrote, and nothing I wrote about him was ever put in the public domain until he had personally signed off on it.

There was another literary project that was being prepared while I was in Lucknow. Using ‘Om Shanti’ as a working title, it aimed to collect and present all the preliminary talks that Papaji gave in satsang in 1991 and 1992. In those days he would begin his satsangs with a short dharma talk. These were powerful teachings that moved and inspired many of the people who listened to them, but they suffered from the usual drawback of looking a bit insipid when the words were transferred to the printed page. Some people who read them couldn’t believe that what they were reading were the same words that Papaji had uttered in satsang. There didn’t seem to be the same power in them on the printed page, irrespective of how much they were tinkered with. I offered some input to the editors, but I was never really involved until Papaji let slip, indirectly, that he wanted me to take up this work as well. By that time several people had made versions of the book, but none seemed good enough to print. Some of the versions had been offered to Papaji, but rather than go through them himself, he would ask other people to read the manuscript and give him an opinion. No one gave a thumbs up to any of the versions that were delivered to him. I really got the feeling that he had little or no interest in this project, despite the enthusiasm of the people engaged in the editing. I don’t think he ever asked anyone to do this work. A group of devotees just took up the work, thinking the material would make a good book.

My belief that Papaji didn’t really have much interest in this book was confirmed when I finally asked him what he wanted me to do with the manuscript that had somehow ended up being my responsibility.

When I told him I thought that it was unfixable, and that I would have to start from scratch if he really wanted a good version to come out, he simply said, ‘We don’t need this book. You can drop the project.’

That left me free to focus on other writing projects that I was actually more interested in, and which Papaji was more enthusiastic about.

I want to revert now to the book of dialogues that Papaji had asked me to compile. When he asked me to do the work, he didn’t tell me to drop everything and do that instead. I think it was something that he wanted me to bring out when I had the time to do it properly. The biography of Papaji I was writing (Nothing Ever Happened) was getting bigger and bigger and consuming more and more of my time. I originally envisaged a single 400-page book, but it ended up being three volumes totaling over 1,200 pages. I only managed to get the final chapters read and approved by Papaji a few weeks before he passed away. I didn’t get a chance to do any work on the book of conversations until I returned to Tiruvannamalai.

I asked a friend of mine, Aruna, who had attended Papaji’s satsangs in Lucknow, to help me by making transcripts of some of the conversations that had taken place in 1991, a time when Papaji was relatively unknown. Satsangs in those days took place in his Indira Nagar living room. About twenty people would normally be there. In later years upwards of two hundred people would crowd into the rented building that Papaji gave satsang in when his home became too small for the crowds that flocked to see him every day. I picked a sequence of satsangs that spanned about six weeks of the summer of 1991.

It was a period of Papaji’s life when he was aggressively challenging everyone who came to see him to look within and find the source of their ‘I’. It made for some great exchanges as the visitors one by one attempted to turn Papaji’s words into a direct experience. This was Papaji’s aim throughout most of his teaching career. He didn’t give people advice on how to go away and practice. He expected people to sit in front of him and discover the substratum of their own true Self as he was cajoling them into doing enquiry , while simultaneously transmitting a power that frequently made people drop their mind-perspective and instead experience what lay behind and beyond it. It was an intoxicating era to be with Papaji. ‘Waking up’ experiences were happening on an almost daily basis in his presence, and one could sense the acute hunger in the questioners who all wanted to be the next person to experience directly what Papaji was pointing at.

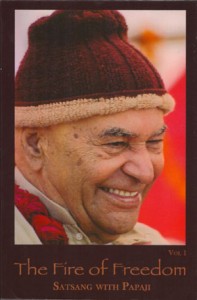

I entitled the book The Fire of Freedom. Papaji used to say that freedom was available only to those people who want it not merely more than anything else, but to the exclusion of everything else. He would give the example of a man whose clothes were on fire, who was running towards a river so that he could jump in and quench the flames.

He would say, ‘You are running towards the river with your clothes on fire. You have only one goal: to get to the water as quickly as possible. If you meet a friend on the way who invites you in for a coffee, do you accept his invitation, or do you keep on running?’

He wanted people to be on fire for freedom, to want it to the exclusion of everything else. When nothing has the power to distract you, you race towards the Self and immerse yourself there. The following story, which I think Papaji made up to make his point, is taken from The Fire of Freedom. It is an elaborate parable that illustrates his basic thesis:

All jivas [individual people] are going home to the Self, but because they imagine themselves to be real, separate entities, they forget about going home and get distracted by other things.

There was once a king who had no children. Since he was getting old and had no heir to succeed him, he decided to adopt one who would be the ruler of the kingdom when he died.

He thought to himself, ‘If I don’t have an established heir in place when I die, there will be a lot of trouble in the kingdom after I die’.

He called one of his guards and asked him to make an announcement that he would open the gates of his palace the following day from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. and that all the people of the kingdom could come in and be interviewed for the job of being the next ruler. No one would be prohibited from coming in.

The next morning crowds of people assembled at the gate, each of them hoping that he or she would be the next ruler. They were greeted by the guards and the courtiers.

One of the courtiers announced, ‘You are about to meet the king and be received by him. You must look good when this happens. Look at you all! Some of you are just dressed in rags. We will clean you all up, give you a nice bath, feed you and give you some nice new clothes, and then you will be presentable to the king. Come with us.’

Everyone was taken into the palace and offered all the facilities that the king enjoyed. For this one day all the visitors had the run of the palace, which meant that they could take and consume whatever they wanted. Those who were interested in perfumes collected bottles of perfume; those who were interested in clothes collected many items of clothing. Other people luxuriated in the king’s baths, ate his food, and watched his dancers and singers perform. This went on all day and everyone forgot what he or she had come to the palace for. The king waited in his throne room, but no one went there to see him because all the candidates were too preoccupied with enjoying themselves with the king’s luxuries. At the end of the day, at 6 p.m., when no one had shown up to claim the throne and the kingdom, the king withdrew his offer and asked everyone to return home.

If anyone had gone to the king immediately, without getting sidetracked, all these treasures would have been his or hers permanently, not just for a few hours. But everyone forgot the purpose for which he or she had come to the palace.

This is what happens to jivas. The throne of the kingdom of liberation is waiting for anyone who wants to walk in and claim it, but these jivas all get sidetracked into enjoying pleasures and accumulating possessions. At the end of their lives they die and get reborn again and continue with their pleasures and sufferings.

You are all so busily engaged with your attachments and desires, you have forgotten the purpose for which you incarnated. You have forgotten that you came here for liberation. What good will these desires, attachments and possessions ultimately do you? What will you leave this world with? Nothing.

Alexander the Great conquered all the known world of his day. All the riches and territories of the world were his while he was alive, but when he died he had nothing. And he knew this. Before he died he gave an order: ‘When you put me in my coffin, leave my hands on the outside. That way everyone will know that I am leaving here with nothing.’

Make the best use of this moment in time, this moment that you have in which you can look at your own Self and not at the objects of your desires. This moment may never come back. If you postpone because you want just a little more enjoyment before you go to the throne room of your own Self, you will be lost, you will be washed away. Your chance will not come again. You can see your own true face only in this moment, not in the next or the last. You have to do it now, not later. In this instant of time you have to devote yourself to your own Self.

To accomplish this you don’t have to study, you don’t have to practise and you don’t have to go to the Himalayas. Just this moment, here and now, is quite enough. Put your face inside and you will see it. Don’t waste this moment. It is a very precious one. I am not going to discourage you. In fact, I congratulate you for being here. There are six billion people in the world, but there are only twenty people here today saying, ‘I want freedom. I want to sit on the throne of freedom.’ Well done! All I ask is that you don’t postpone. You have been postponing all your life – ‘I will do it later today, tomorrow, next week, next year,’ and so on.

Postponement is the mind. Mind is the past. Mind is manifestation. Manifestation is samsara. And samsara is suffering. You have to choose and decide what you want, and you have to choose in this instant of time, not later on. In this instant look at your own Self. If you allow this moment to slip, it will become the past. Don’t allow it to slip….

All are enjoying, eating and dancing. Whose fault is this? Freedom is waiting for you with extended arms, but you are not responding to the loving embrace that it wants to give you. You are otherwise engaged. What you don’t understand is that when you try to get happiness from all these objects of pleasure, you are really searching for the happiness of your own Self. Your search is simply misdirected. You are all looking for happiness, but you never find it because you are all looking in the wrong place. If you find the correct place to look, instantly you will get it. That instant is the moment you drop all the pleasures of the king’s courtyard and walk directly into the throne room to meet the king. How much time do you need to do this? How much time does it take to turn your back on all these enjoyments in order to accept the invitation of the king? In this story, the gate was open for twelve hours, from six in the morning until six in the evening. In your lifespan you have eighty years. You can enjoy that life, but remember that the most important thing you have to do in this incarnation is to run into the king’s throne room and claim that prize. Don’t postpone. Don’t think that you have time to do it later. Make it your first priority. Reject transient pleasures and run inside to meet your inner king. Once you have done that, the whole kingdom will be yours.

I originally planned to make several volumes of The Fire of Freedom since there is a vast amount of material available that could fill several more books. One day, when I have time, I hope to get back to this series.