While I was working on this book in Tiruvannamalai, I was also engaged in a long-term project to bring out a new English translation of Guru Vachaka Kovai. Robert Butler, Venkatasubramanian and I had moved on to this after we had completed Padamalai.

Guru Vachaka Kovai is, in my opinion, the most complete and the most authoritative collection of Bhagavan’s spoken teachings. Since this is a bold claim to make, I feel I should explain why I came to this conclusion.

In the 1920s and 30s Muruganar, the compiler of Guru Vachaka Kovai, wrote down teaching statements that he heard Bhagavan make, recording them in the form of four-line verses. He would show these verses to Bhagavan on the day he recorded them. Bhagavan would either approve them on the spot, or make some suggestion on how they could be made more accurate. Bhagavan’s knowledge of Tamil prosody was almost as good as Muruganar’s, so he was often able to suggest improvements to the style as well as the contents of the verse.

Although Muruganar had the kind of mind that enabled him to compose, almost spontaneously, Tamil verses on any aspect of Bhagavan’s teachings, he didn’t have the kind of intellect that would allow him to organise this collection of teachings in a coherent way. When about 800 of these verses had been recorded, Bhagavan handed them over to Sadhu Natanananda and asked him to arrange them thematically so that they could be printed in book form. During Bhagavan’s lifetime all of Muruganar’s literary works were published by Ramanapadananda, a devotee of Bhagavan who made it his life’s work to raise money for the publication of Muruganar’s poetry. He would travel around the country, giving public readings from Muruganar’s poems, and encouraging his audiences to contribute money to future publications. On one occasion he even went on a tour of South-East Asia to collect funds for his publication projects.

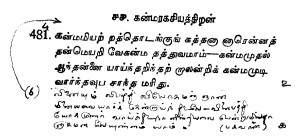

Sadhu Natanananda sent his arrangement of Muruganar’s verses to Ramanapadananda, who printed out a proof copy for Bhagavan to read and check. And this is where the story gets really interesting. Bhagavan went though the manuscript word by word, revising some of the verses, changing the sequence of others to make the continuity of the arguments more clear, and occasionally adding extra verses of his own. After Bhagavan had finished his editing work, there were twenty-four of his own verses interpolated among over 800 of Muruganar’s. The proof copy that Bhagavan went through has been preserved in the Sri Ramanasramam archives, allowing us to see what Muruganar wrote, how Sadhu Natanananda arranged the verses, and how Bhagavan edited and rearranged the material himself. Here, for example, is an extra verse that Bhagavan composed. The arrow indicated where he wanted it to appear in the text.

Bhagavan’s new verse says:

Simply to enquire, ‘Who is it that experiences this karma, this alienation [vibhakti], this separation [viyoga] and this ignorance?’ constitutes in itself [the paths of] karma, bhakti, yoga, and jnana. For when, upon enquiry, the ‘I’ ceases to be, these [karma, and so on] are [known to be] eternally without existence. Only abiding as the Self is the state of reality.

In addition to editing the teaching portions, Bhagavan made two significant changes to the introduction and prefatory verses that indicated his high regard for Muruganar and his appreciation of the text itself. The final prefatory verse was originally composed by an anonymous admirer of Muruganar who praised Muruganar and the efforts he had made to record the teachings of Guru Vachaka Kovai. This is what he wrote:

Holding in his heart as the supreme truth the feet of illustrious Ramana, God manifesting in the form of the Guru, [Muruganar revealed] the ambrosial truth of all things. Declare that his name is Mugavai Kanna Murugan of the Bharadwaja lineage.

Mugavai is an alternative rendering of Ramanathapuram, Muruganar’s home town, and Kanna is the Tamil version of Krishna, the name of Muruganar’s father. When Bhagavan saw these lines, he crossed out almost all of the original words and replaced them with a verse of his own:

He who [recorded and] strung into a garland a few of the Guru’s instructions and announced this pre-eminent scripture to the world is Kanna Murugan, who sees through his eye of grace that the essence of all things is only the far-reaching feet of his Lord.

The word translated as ‘pre-eminent scripture’ (paramarttam) can also be translated as ‘Supreme Truth’, ‘Supreme treasure’, or ‘Treasure of jnana’. Whichever phrase one chooses, it is a high accolade given by Bhagavan to this collection of teachings. It is also worth noting that in the final portion of the verse – ‘Murugan, who sees through his eye of grace that the essence of all things is only the far-reaching feet of his Lord’ – Bhagavan is confirming that Muruganar is having the experience of seeing everything as the Self.

Bhagavan made an even more significant editing intervention in the introduction that had been written by the editor and compiler, Sadhu Natanananda. Towards the end of this introduction Natanananda had written the following sentence:

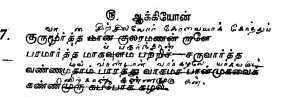

Natanananda’s sentence can be translated as:

In summary, it can be said that this is a work that has come into existence to explain in great detail and in a pristine form Sri Ramana’s philosophy and its essential nature [swarupa].

Look at the last line where an extra syllable was subsequently inserted by Bhagavan. He added the suffix ‘ay’ after the word ‘idu’, which by itself means ‘this’. This insertion makes a significant difference to the meaning of the sentence.

The addition of this suffix can give two meanings that can be roughly translated as ‘this definitely’ or ‘this alone’. Sometimes both meanings can be taken simultaneously. Bhagavan is either saying:

(a) … this work alone has come into existence to explain in great detail…

(b) … this work indeed has come into existence to explain in great detail…

Or both meanings may be indicated. Whichever option one takes, Bhagavan’s editorial insertion at this point gives an exceptional and unique imprimatur to this collection of teachings.

There are several large books that contain the conversations that Bhagavan had with visitors and devotees: Day by Day with Bhagavan, Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi and Letters from Sri Ramanasramam spring to mind. Virtually none of the material that appears in these books was ever seen or checked by Bhagavan. Some of the smaller books of conversations, such as Spiritual Instructions and Maharshi’s Gospel were seen and checked by Bhagavan during his lifetime, but none is as comprehensive as the teachings that were assembled in Guru Vachaka Kovai.

Bhagavan’s role in checking and revising Guru Vachaka Kovai was the main reason I signed on to this project to bring out an authoritative new English translation of this work. I felt that a work of this authority and magnitude deserved to be made available in a comprehensive English edition. Other versions had appeared before, but parts of them were either paraphrased or were not complete, and none of them had incorporated all of Muruganar’s own comments and explanations. We utilised Muruganar’s own prose renderings of the verses, his notes, additional verses from a work entitled Anubhuti Venba that contained explanations of some of the verses, and we also added many quotations from other Ramana books that complemented or expanded on the teachings that were found in the original verses.

Venkatasubramanian, Robert and I spent four years (2004 to 2008) translating and editing our presentation of this text. A few appreciative devotees donated money to subsidise the printing, enabling us to bring out a 650-hardback that retails in India for Rs 150 ($2.50).

I should mention in passing that Muruganar’s works seem to attract patrons. I have already mentioned Ramanapadananda who went on fund-raising tours to collect contributions that would allow him to continue to publish Muruganar’s work during Bhagavan’s lifetime. I also mentioned how Prof. Swaminathan procured a grant from the Central Government in New Delhi that allowed the Ramana Centre there to publish the nine volumes of Sri Ramana Jnana Bodham at Rs 10 (16 cents US) per copy. Last year I was approached by a group from Andhra Pradesh who wanted to bring out a Telugu edition of our translation of Guru Vachaka Kovai. They didn’t even want to charge people for the book. They gave all the copies away to devotees and Ramana centres in the state.

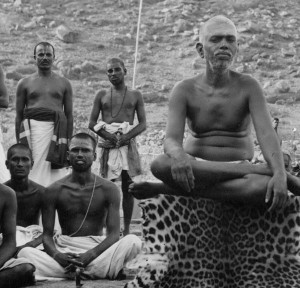

When Muruganar first came to see Bhagavan in 1923, he was primarily interested in finding a Guru who could grant him liberation. He also wanted to have a Guru-disciple relationship that was similar to that between Manikkavachagar (a Tamil poet-saint who lived over a thousand years ago) and Siva, who manifested in person to be his Guru. A poem that Muruganar composed in the Arunachaleswarar Temple when he was on his way to see Bhagavan for the first time, hinted that he was looking for this kind of relationship.

On his second visit a few weeks later he composed a poem of his own that was modeled on one of Manikkavachagar’s more famous compositions and presented it to Bhagavan. It even had the same title: ‘Tiruvembavai’.

Bhagavan sensed this inner desire of Muruganar to be the poet who burned with love for his Guru and who composed ecstatic verses in praise of him. Sadhu Om has described how Bhagavan gave his permission to proceed with his ambition:

He [Muruganar] one day composed his ‘Tiruvembavai’ beginning with the words ‘Annamalai Ramanan’. Seeing that the verses of that song were replete with many sublime features similar to Manikkavachagar’s Tiruvachakam, Sri Bhagavan playfully asked, ‘Can you sing like Manikkavachagar?’ Though Sri Muruganar took these words to be a divine command from his Guru, he prayed to him, ‘Where is Manikkavachagar’s divine experience of true jnana [true knowledge], and where is my state of ajnana [ignorance]? Only if Bhagavan removes my ajnana by his grace will it be possible for me to sing like Manikkavachagar; by the mere talent of this ego, how is it possible to sing like him?’

Despite his misgivings Muruganar accepted the commission from Bhagavan and began to compose a work, Sri Ramana Sannidhi Murai, that was modelled on Manikkavachagar’s classic devotional text. I am guessing that he worked at it intermittently, between his other projects, because it was nine years before the first edition was published in 1933, and even then the work was far from complete. In Manikkavachagar’s Tiruvachakam there is an opening poem entitled ‘Siva Puranam’ that praises and thanks Siva effusively. The first edition of Sri Ramana Sannidhi Murai had no equivalent introduction. Muruganar decided that one was needed for the next edition of the book. He began to compose a poem, in Bhagavan’s presence, that was closely modelled on ‘Siva Puranam’. Sitting in the Old Hall in front of Bhagavan, he managed just over 200 lines before he decided to take a break. He wanted some time to think about what would come next, and he also needed a break to think about a suitable title. The poem he was modelling his efforts on was entitled ‘Siva Puranam’ because it praised and glorified Siva. Since Muruganar saw Bhagavan as Siva in human form, he thought that he might use the original title for this new work. However, he also toyed with the idea of changing it to ‘Ramana Puranam’. ‘Puranam’ by the way, can be translated as ‘history’ or ‘ancient story’.

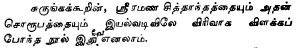

When he returned to the hall several hours later, he discovered that matters had been taken out of his hands. Bhagavan had picked up his manuscript and had written ‘Ramana Puranam’ at the top of every page. The title issue had been resolved, but Bhagavan had not stopped there. While Muruganar was out walking, Bhagavan had picked up his pen and completed the work, adding over 300 lines to the poem. Though this extensive contribution is the longest piece of poetry that Bhagavan ever composed, Bhagavan’s role in completing the work was not widely known, and the portion he composed has never appeared in his Collected Works.

As the work was being prepared for publication a proof copy was given to Bhagavan to read and approve. Muruganar had written a footnote indicating which section had been composed by him and which lines had been added by Bhagavan.