(Parts of this article were first published in The Mountain Path, 1990, pp. 64-71)

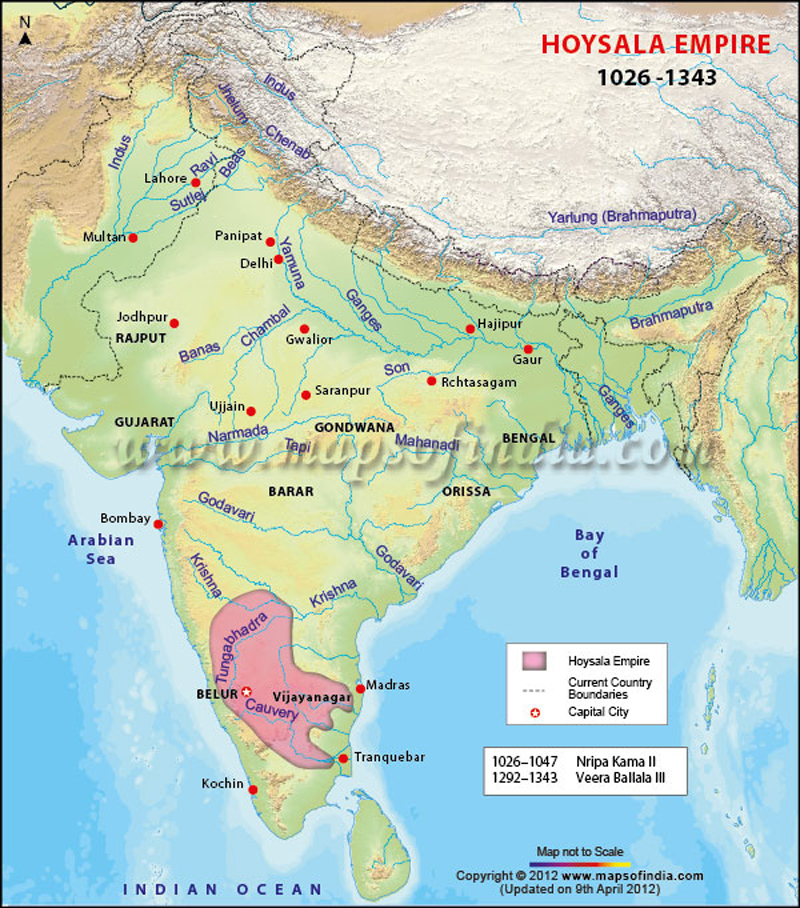

King Vira Vallalan III was an illustrious king who ruled over the Hoysala empire from 1292 till 1342. At its peak it covered a large part of South India. Its traditional stronghold was the southern part of the Deccan plateau where the capital city Dwarasamudra was located. The city, nowadays reduced to a very small town called Halebid, lay to the north-west of Mysore. Though now ruined and abandoned, the old city contains the finest examples of Hoysala art and architecture, a unique style distinguished by a high density of details and embellishments. When times were good and neighbouring kingdoms were weak, the Hoysala empire covered most of modern-day Karnataka, northern Andhra Pradesh, and a good portion of northern Tamil Nadu.

King Vallalan’s devotion and piety are celebrated in chapter seven of the Arunachala Puranam, a Tamil poetical work that was written in the sixteenth century by Ellapa Nayinar. The work is based on the Arunachala Mahatmyam, written several centuries before in Sansksrit, but the chapter dealing with King Vallalan and his exploits in Tiruvannamalai can only be found in the Tamil version. To find out why he is so revered in Tiruvannamalai, and indeed, why he was in Tirvannamalai at all, it is necessary to go back a few years and give an account of his family history.

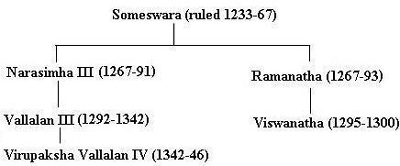

King Vallalan’s grandfather, Someswara, ruled the empire from 1233-67. At the beginning of his reign he recaptured territory lost by the previous king, extended his kingdom northwards as far as Pandharpur in Maharashtra, and endowed the famous Vittal Temple there. In the later years of his reign both his northern and southern territories were attacked by neighbouring kingdoms. The resurgent Pandya kings of Madurai, in particular Sundara Pandya, took over much of his Tamil territory, including Tiruvannamalai, which was then part of a territory known as Magada. This covered most of the old, undivided North Arcot District, along with a small portion of South Arcot. Towards the end of his life Someswara divided his kingdom between his two sons: Narasimha received the northern territories and the capital city Dwarasamdura, while Ramanatha was given the diminished southern ones whose chief city was Kannanur, located about fifteen miles north of Tiruchirappalli. The Pandya King Kulasekara, based in Madurai, captured most of Ramanatha’s Tamil territories in 1279, forcing him north. Ramanatha then tried to take some of his brother’s territories by force, but only succeeded in capturing a few districts in the Bangalore area.

Narasimha died in 1291, leaving King Vallalan in charge of a much truncated empire. Vallalan was crowned king on 31st January, 1292, when he was thirty years old, and he continued to rule until he was well over eighty.

Ramanatha, ruler of what remained of the southern Hoysala territories, did not dispute King Vallalan’s succession, although both he and his son were hostile to him. However, because they had little power and only a small territory, when Viswanatha died in 1300, Vallalan easily succeeded in uniting the Hoysala empire under his rule.

Vallalan wanted to regain his family’s southern territories, but was in no hurry to do so. However, in 1310 an opportunity arose. His grandfather, Someswara, had made strategic marriage alliances with the Chola and Pandya kingdoms in the South, so when the Pandyas requested his assistance in defeating an illegitimate claimant to their throne, he saw his chance and moved his army south. Unfortunately, in committing himself to this campaign he left himself open to an attack in the north.

In 1311 the Delhi Sultan, Ala-u-din Khalji sent his favourite slave general, Malik Khafur, on a buccaneering expedition to the kingdoms of the South. Knowing that King Vallalan was campaigning on the extreme southern borders of his empire, he invaded from the north and began to loot the northernmost Hoysala territories. When King Vallalan heard the news, he raced back to Dwarasamudra, but he was too late to save the city. Malik Khafur was so firmly entrenched there, King Vallalan was forced to surrender on his arrival. Malik Khafur was not seeking to expand the borders of the Delhi Sultanate; he was merely engaging in a military treasure-hunt on the Sultan’s behalf. King Vallalan was obliged to hand over all his treasure, including his horses and elephants, to the general. One tradition asserts that he agreed to hand over everything he owned except for his sacred thread, and that he walked away from the surrender ceremony naked except for this string dangling from his shoulder. Sultan Ala-u-din permitted him to carry on ruling the Hoysala empire on condition that he pay an annual tribute to the Sultanate. To all this King Vallalan agreed.

Malik Khafur continued his piratical raids all over the South, getting almost as far as Madurai. On his return to Delhi he handed over to the Sultan 612 elephants, 96,000 gold coins, several boxes of jewels and pearls, and 20,000 horses. It was an astonishing military accomplishment. For over a year his retreat had been cut off by hostile Hindu kingdoms, but he responded by moving even further forwards. Somehow, he kept his army and his treasure intact, won every battle he engaged in except for one near Madurai, and returned to Delhi in triumph.

When Malik Khafur was safely back in Delhi, King Vallalan went back to Tamil Nadu to carry on his campaign for Sundara, the Pandya king who had asked for his support. As a reward for the assistance he offered, he was granted some territories in a region called Tondaimandalam, an area covering parts of northern Tamil Nadu. The grant included ‘Annamalai-rashtra’ – ‘the country around Annamalai’. Shortly afterwards, possibly around 1315 or 1316, he decided to make Tiruvannamalai his southern capital, calling it Aruna-samudra – The Ocean of Aruna. An epigraph in the Arunachaleswara Temple, dated 1317, has the king proclaiming the town as his southern capital. In this same inscription the king made many endowments to the temple and contributed money for building projects there.

Having a large territory to defend and expand, King Vallalan spent little time in his new capital. In the years that followed he was active on his northern borders, campaigning against a powerful chief of the Kampili kingdom. Elsewhere he had moderate success in forging an anti-Muslim alliance between the Hindu states who were trying to oppose the Muslim invasions from the North. He found allies in what is now Andhra Pradesh and with their support drove a Muslim ruler out of the Telengana region and forced him to retreat to Delhi. In the South he defeated the Muslims who were encroaching on the northern part of the Pandya kingdom. In this territory he appointed a vassal king from the Sambuvaraya lineage, native chiefs of that area, to rule for him. A few years ago North Arcot District, in which Tiruvannamalai was located, was bifurcated. The southern half, with Tiruvannamalai as it headquarters, was named Tiruvannmalai-Sambuvarayar after these rulers.

By diplomacy, by military prowess and by forging opportunist and strategic alliances, King Vallalan kept the Hoysala empire more or less intact at a time when all the other Hindu kingdoms were falling to the Muslims. When the Pandya kingdom fell to the Delhi Sultanate in the latter half of his reign. Hoysala was left in the somewhat besieged condition of being the last, major independent Hindu state in the South.

King Vallalan had allied himself with the Delhi Sultanate on various minor matters. As a reward he was permitted to remain independent, although he nominally owed allegiance to Delhi. But even that allegiance did not save his northern capital, Dwarasamudra. Around 1327 the new Sultan of Delhi, Muhammad Bin Tughlak sent out an army and destroyed it. For the remaining fifteen years of his reign he was based at his southern capital of Tiruvannamalai and launched all his campaigns from there.

Having set the scene with what I hope was not an inordinately-long history lecture, it is now time to see what the Arunachala Puranam has to say about Tiruvannamalai, King Vallalan and his exploits there. I have annotated the story with a few comments of my own.

452

Now we will tell you the story of King Vallalan to whom God Himself manifested as a child and then bestowed His grace by giving him a boon.

453

In a famous place called Arunai [Tiruvannamalai] there are mansions with jewel-bedecked pinnacles and gardens dense with fruit-giving trees that reach up to the starry firmament. In this place dwell beautiful devadasis [temple dancers] equal only to Arunadhati [Vasishta’s wife] in chastity.

454

Vallalan, the king of this renowned city, has a virtuous character, speaks only the truth, and with great devotion takes care of all beings as if they were no different from himself. He belongs to that Agni lineage, whose fame cannot be described. The king came [to this world] to worship daily the feet of Parameswara [the Supreme Lord], to do service to Him and to praise Him.

In claiming an aristocratic pedigree, one can do no better than claim that one comes from the Solar, Lunar or Agni lineages since these are the branches of the human race that brought forth many of the illustrious characters of Indian mythology. Ellapa Nayinar’s claim that King Vallalan belonged to the Agni lineage was not supported by King Vallalan himself. In an epigraph that I quote below, he firmly places himself in the Lunar dynasty.

First a word about epigraphs: Indian history has been largely reconstructed from engravings on stone, called epigraphs after a Greek word which means ‘written on’, which are found all over the country. In ancient times stone walls were used as a kind of public registry office. The activities of kings and their subjects, the transfer of land and possessions, decrees, grants, endowments and much else were all recorded in stone for posterity. The Tiruvannamalai temple has a rich collection of epigraphs chiselled on its masonry, some of which date back to the ninth century. There are nine from King Vallalan’s reign (nos. 301-309) of which no. 301, which was only discovered in the 1980s, is by far the most important. Dated 1317, it begins by describing King Vallalan’s ancestry and virtues. Epigraph numbers are all taken from the definitive edition published by Institute Francais de Pondicherry: Tiruvannamalai, a Saiva Sacred Complex in South India, volume one, part one, ‘Inscriptions’. Ed. P.R. Srinivasan, published in 1990.

From the lotus of [Vishnu’s] navel arose Brahma, the creator of all men. From his mind was born Atri. Then Soma [the moon] was born in his eye. In [his family] was born the king Someswara. To him was born Narasimha who was like a lion to his elephant-like opponents. From him whose gifts eclipse those of the heavenly tree [the kalpa-vriksha or wish-fulfilling tree] whose wealth eclipses that of Kubera [the god of wealth] … and whose prowess eclipses that of the terrible blaze emanating from the forehead eye of the God having the bull as His vehicle [i.e. Siva] was born the king Vallaladeva. The illustrious King Vallaladeva, possessing all auspicious things, was staying at his capital, which was distinguished by the name Aruna-samudra, belonging to the Hoysala kingdom, which was established with love by his father, which possessed the wealth of a kingdom, and which was the abode of real riches.

The Arunachala Puranam continues:

455

He had no desire for the possessions of others. Excepting his own wives, he considers all other women as his sisters and treats them accordingly. In accordance with the law, he is given one sixth of his subjects’ earnings as taxes. He serves with great delight as a patron of the temple of the Lord who held the poison in His throat.

I will comment later on King Vallalan’s status as a patron of ‘The temple of the Lord’. For the moment I will restrict myself to his accomplishments as a tax gatherer.

Epigraph 303, carved in 1341, towards the end of his reign, gives details of some of the taxes that were imposed on his subjects. The list may be far from complete; it is simply a list of those taxes deemed worthy of mention in one edict:

1) a tax on goldsmiths.

2) a tax on tailors.

3) a tax on oil presses.

4) a tax on looms.

5) a tax on fishing.

6) a tax on doors.

7) a tax on owning a mirror.

8) a tax on the plot of land on which one lived.

9) a fee payable to village rulers.

10) a special tax for some people who had to supply a free ox to the government.

11) a tax to be paid in gold – by whom and what for is not mentioned.

12) a general government levy under which ‘common people’ had to supply goods to the government.

In addition to these, which had probably been in force for some time, a new tax bearing the name of King Vallalan himself was introduced. It was not mentioned who was to pay the tax. The ordinance was promulgated on January 4th, 1341, a time when King Vallalan was living in Tiruvannamalai and using it as a base for military adventures against the Muslim rulers of Madurai. The tax may therefore have been a special war levy.

Rulers are rarely satisfied with their income, and their subjects are usually unwilling to give as much as a government thinks it needs. Tiruvannamalai in 1341 was no different in this respect. On top of all the above levies there was a ‘nattuviniyokam‘, a tax to be paid by everyone to make up the perceived shortfall in the other taxes. Since no percentages or amounts are given, it is not possible to determine whether the one-sixth law suggested by Ellapa Nayinar was actually adhered to.

Though the taxes may have been onerous, I suspect that the citizens of Tiruvannamalai would have welcomed the king and his entourage with open arms. Royal patronage for the temple (which meant many, many jobs) along with the chance to earn money from the thousands of soldiers, courtiers and camp followers of the king, would have initiated an economic boom in what previously would have been a sleepy, provincial outpost.

456

In this place tigers and cows dwell together, drinking from the same tank. The brahmin preceptors recite the Vedas, and all the people listen. To obtain grace from the ancient Lord, people decorate the city, making it a marvel to behold. Maidens sprinkle water in the street and make magnificent kolams [geometrical patters made from rice flour].

457

There are three rainfalls a month and the abundantly rich harvests never fail. Those who ask for food are immediately invited and offered food with the six different flavours. By serving the tapasvins [those performing tapas] and giving whatever is asked of them, the people receive blessings. In the temple of Siva, the Just One, they light ghee lamps and do puja regularly.

458

Thus, the great city existed in all its splendour according to God’s design. But even though the king had all possible wealth, he had a troubled mind because he had no son to speak his name.

‘To speak his name’ means to perform the funeral ceremonies after his death. It was traditionally believed that the son had to perform the last rites in order to send his father’s soul to the next world.

The central theme of this chapter from the Arunachala Puranam is King Vallalan’s quest for a son. This is most curious since it is well known that he already had a son at the time he moved to Tiruvannamalai. When Malik Khafur sacked Dwarasamudra in 1311, he took King Vallalan’s son to Delhi as a hostage, hoping thereby to ensure the king’s good behaviour. The son, Virupaksha Vallalan, was treated well during his captivity. He was released after some time and on 6th May, 1313, arrived back in Dwarasamudra. The event was commemorated in an inscription there that notes that his father diverted some of his tax income to ‘God Ramanatha at Kudali’ (Srirangapattanam in Mysore) to show his gratitude for his son’s release. Virupaksha Vallalan eventually succeeded his father and outlived him by at least several years.

Why then was King Vallalan complaining while he was in Tiruvannamalai that he needed a son? The answer, I think, is that he wanted a worthy son to succeed him. King Vallalan had a very low opinion of his son’s capabilities, a conclusion that can be inferred from the fact that he was given no responsibility whatsoever for the running of the kingdom. In an age when it took weeks or even months to move an army from one end of the country to another, it was imperative to have able lieutenants with leadership abilities who could lead troops in local encounters and solve all provincial administrative problems. King Vallalan had such subordinates to whom he devolved much of his authority, but his son was not among them. As early as 1309 he was depending heavily on one of his nephews and by 1328 he had a trusted cabinet of seven: two were his nephews and five were commoners. Each of them was given the power to rule autonomously in the absence of the king.

There is a Nandi mantapam in the Arunachaleswara Temple that was built at King Vallalan’s behest. On one side of the pedestal, below the Nandi, can be seen eight men in two groups. One group represents the king and his two nephews; the other group of five are the non-royal members of his cabinet.