Several years ago a friend of mine in California asked the following question by email:

Which books do you feel are the most genuine documentations of Ramana’s words and teachings? Even the Talks was published several years after his death, though it reads consistently throughout. I have only seen the original translation of Who am I?, the small green booklet, and was unaware that there are other translations. How do these all compare for authenticity and clarity?

Through circumstances that I can’t quite remember, the reply I sent ended up being posted online. I then found myself defending and clarifying some of the points I had made. I have just dusted off that particular series of correspondence and amalgamated all the points into one presentation. These are my thoughts on this topic, along with the reasoning behind them. It is a bit of a touchy subject and I suspect that some devotees will disagree with me. This was the first question:

I have only seen the original translation of Who am I?, the small green booklet, and was unaware that there are other translations. How do these all compare for authenticity and clarity?

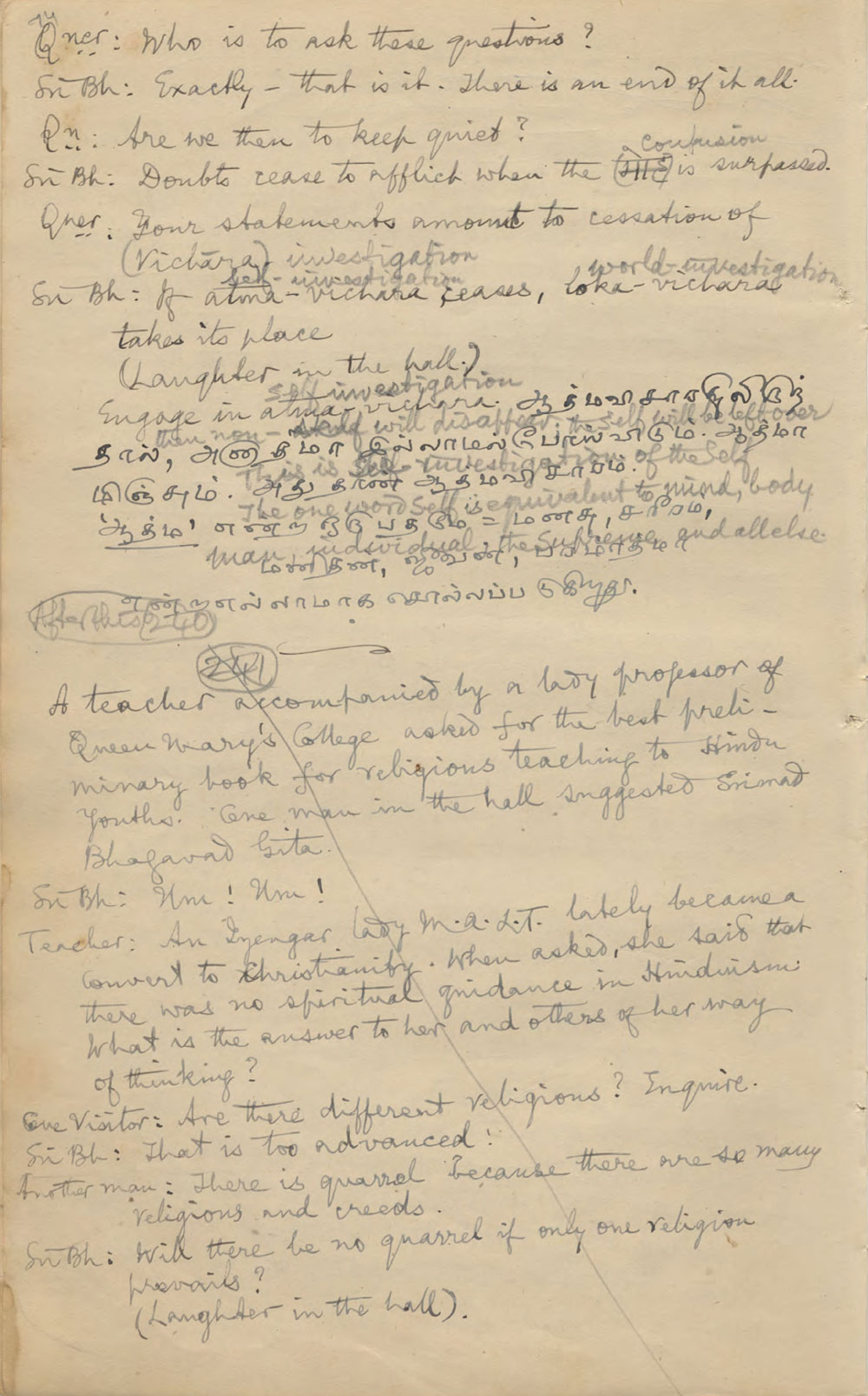

There have been several translations of Who Am I?, some better than others. There are also several versions of the original text, which complicates matters. It has appeared as a question-and-answer version with the number of questions varying from thirteen to thirty. The essay version composed by Bhagavan himself is the most authentic because the original question-and-answer version that appeared in 1923 was composed and edited by Sivaprakasam Pillai and was not shown to Bhagavan prior to its publication.

Sivaprakasam Pillai questioned Bhagavan in 1902 and Bhagavan wrote down his replies either in the sand or on a slate, After each new question had been asked, the preceding reply was wiped out to make space for the new answer. Only the last one was not erased. Sivaprakasam Pillai then went home and wrote down what he could remember of this conversation. Given the circumstances of the questioning, it is possible that some errors crept in since the recording was dependent on Sivaprakasam Pillai’s memory of the replies.

Who am I? was first printed in Tamil in 1923 as an appendix to Sri Ramana Charita Ahaval, a verse biography of Bhagavan by Sivaprakasam Pillai. It was an immediate success with devotees. In 1926 Bhagavan rewrote the whole work in the form of an essay. This should be regarded as the standard and authentic text. During Bhagavan’s lifetime Bhagavan insisted that this book be subsidised so that new visitors to the ashram could have a short and accurate summary of his teachings. Many translations were brought out, and these too were subsidised so that non-Tamil speakers could have access to these key teachings. When new visitors asked what his teachings were, he would sometimes ask them to read Who am I? and then ask questions afterwards.

Although the essay version should have superseded the question-and-answer version, the question-and-answer version continued to be printed in various formats. However, over the next few years its text was back-edited to make it conform more closely to the essay version. Nowadays, there is very little difference between the two texts. Next question:

Which books do you feel are the most genuine documentations of Ramana’s words and teachings?

At the top of this list has to be Bhagavan’s own writings, the works that appear in The Collected Works of Sri Ramana Maharshi. These would include Who am I?, Ulladu Narpadu, (Forty Verses) Upadesa Undiyar (Upadesa Saram), the five hymns to Arunachala and a few other smaller works. These were all composed by Bhagavan and checked by him during his lifetime. However, I should make it clear that Bhagavan only checked the Tamil, Telugu, Sanskrit and Malayalam versions of his writings that appeared during his lifetime. The later European-language translations of these works are only as good as the understanding and the linguistic ability of the person doing the translating. The first English edition of Collected Works was not published until the 1950s, after Bhagavan had passed away. I do not know of any English translations of these works that were checked and revised by Bhagavan except for some that were done by Major Chadwick. These were rather free, rhyming translations, rather than accurate renditions of the original philosophical ideas.

I would also include the portion of Ramana Puranam that was composed by Bhagavan on this list of works that have the highest authority and authenticity. In the 1930s Muruganar began a long Tamil poem in praise of Bhagavan, but stopped when he had written about 200 lines. He went out for a walk, and when he returned he discovered that Bhagavan had completed the poem by adding another 300 or so lines. Although much of this poem is a hymn in praise of Bhagavan, it also includes many teaching statements that summarise or elaborate on ideas that had already appeared in some of Bhagavan’s earlier philosophical poems.

Of the texts that appear in Collected Works and which are attributed to Bhagavan, Vichara Sangraham (Self Enquiry) occupies a bit of a grey area for me. Like Who am I?, this work arose from replies that Bhagavan wrote out in the period, around the start of the twentieth century, when he was not speaking. However, the content has one important difference. Sivaprakasam Pillai was asking questions on the nature of reality and the means of discovering it; Gambhiram Seshayya, the devotee who recorded the Vichara Sangraham answers, was more interested in getting an understanding of passages in Tamil spiritual books that he couldn’t understand because either the language or the philosophy was too difficult for him. He showed Tamil spiritual books to Bhagavan and asked him to summarise key passages from them in a simplified form. Bhagavan then wrote out paraphrases of these texts. Some of the teachings in Self Enquiry are clearly Bhagavan’s own, and were probably written in response to questions put by Gambhiram Seshayya, but they are mixed with material that is simply Bhagavan’s presentation of ideas taken from other books that he didn’t necessarily agree with.

All this would not matter so much if Bhagavan had, as he did with Who am I?, produced his own authoritative version of the text at a later date. Unfortunately, he did not write either the question-and-answer version that first appeared in Tamil around 1930 or the Tamil essay version that was first printed in 1939. Both of them were written and edited by Sadhu Natanananda. I am sure that Bhagavan checked and approved the versions that ended up in Collected Works, but one cannot really say that either was his own work.

The original source of Self Enquiry is the notebook that Gambhiram Seshayya’s relatives sent to the ashram in 1930. Since this notebook no longer exists, it is no longer possible to determine exactly how this work evolved from the original notes to the final published version.

While the works that appear in Collected Works have the highest provenance and the greatest authority, I believe that the version of Guru Vachaka Kovai that came out in Tamil in 1939 has an almost equal authority. Throughout the 1920s and 30s Muruganar sat in the hall and listened to Bhagavan give out his verbal teachings. Whenever Bhagavan said something that Muruganar thought was worth recording, Muruganar would write it down in the form of a four-line Tamil verse. These short and pithy recordings were shown to Bhagavan on the day that they were written, allowing Bhagavan to check their veracity. Sometimes Bhagavan would make corrections to the verse and return it. In 1939 all these verses were assembled and arranged by subject by Sadhu Natanananda, the man who wrote and edited the Tamil versions of Self Enquiry. Bhagavan went through a proof copy of Guru Vachaka Kovai and made major revisions to many of the verses. He also added a few verses of his own. After he had completed his editing work, Bhagavan turned his attention to the introduction that had been written by Sadhu Natanananda. There he found this statement:

In summary it can be said that this is a work that has come into existence to explain in great detail and in a pristine form Sri Ramana’s philosophy and its essential nature.

Bhagavan added one word to this sentence that makes an enormous difference to its meaning. After he had edited it, the sentence read, ‘… this work alone has come into existence to explain in great detail and in a pristine form Sri Ramana’s philosophy and its essential nature.’

This interpolation by Bhagavan himself gives the highest imprimatur to this work. Editions of Guru Vachaka Kovai that came out after Bhagavan had passed away included verses that Bhagavan had not personally edited in this way, so their authority is slightly less, but even so, I would regard Guru Vachaka Kovai as the most authoritative collection of Bhagavan’s verbal teachings. It is also worth noting that it is recorded in Tamil, the language in which Bhagavan generally gave out his teachings. Other compilations of his verbal teachings were recorded in English (Talks, Day by Day) or Telugu (Letters from Sri Ramanasramam). The versions of them that now appear in Tamil are translations, not original texts.

If anyone is interested in tracking down the verses that appeared in the 1939 Tamil edition of Guru Vachaka Kovai, there are some appendices in our (Venkatasubramanian, Robert Butler and myself) translation of Guru Vachaka Kovai that will facilitate this search.

Next, in order of authenticity and reliability, are the records of conversations that appeared during Bhagavan’s lifetime which were checked and edited by him prior to publication. This list would include Maharshi’s Gospel, Spiritual Instruction, and to a lesser extent the talks that precede Sat Darshana Bhashya.

There is a proof copy of the first edition of Maharshi’s Gospel in the Ramanasramam archives which shows that Bhagavan made minor handwritten revisions to the text prior to its publication.

Spiritual Instruction has always appeared in The Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi, even though it is a record of answers Bhagavan gave out, rather than a written work. All the items that appeared in the Tamil edition of Collected Works have been thoroughly checked by Bhagavan himself.

The dialogues that precede Sat Darshana Bhashya were read to Bhagavan by Kapali Sastri prior to their publication. As he was listening to them, Bhagavan made suggestions that were all incorporated. K. Natesan, who was present in the hall on the day of the reading, told me that Bhagavan asked Kapali Sastri to change one phrase to ‘import of I’ – a nice English phrase – but he couldn’t remember what words it replaced. Though Bhagavan listened to this reading and made a few suggestions that were accepted, there are several comments that were attributed to Bhagavan in the work that I doubt very much he said. These remarks support an interpretation of Bhagavan’s teachings that was espoused by Ganapati Muni and Kapali Sastri, but which Bhagavan refuted on other occasions. I suspect Kapali Sastri put these words into Bhagavan’s mouth, and Bhagavan, knowing that Kapali Sastri subscribed to these views, was unwilling to make adverse comments on them when they were read out to him in the hall.

This is a feature of Bhagavan’s editing that I will return to later. Some people, such as Muruganar, had their texts vigorously edited by Bhagavan, whereas others were allowed to get away with somewhat dubious statements because Bhagavan didn’t invest the same energy in correcting their manuscripts.

Sri Ramana Gita, which was also published during Bhagavan’s lifetime is, to my mind, extremely problematic. It was not shown to Bhagavan prior to its publication, and G. V. Subbaramayya has recorded an incident in which Bhagavan wanted to change the original Sanskrit of one verse because a particular term was inappropriate. The first edition was not published by Sri Ramanasramam, but when the ashram took over the book, subsequent editions were checked by Bhagavan before they were printed. Bhagavan also took care to ensure that the editions of Sri Ramana Gita that were published in other languages were accurate. I visited K. K. Nambiar in Chennai in the early 1980s and he showed me the Malayalam edition of Sri Ramana Gita that he and Bhagavan had worked on together. Bhagavan had eventually written out all eighteen chapters in Malayalam, and this handwritten copy was sitting on Nambiar’s altar when I visited. He told me that he recited the whole work in Malayalam every day as parayana.

Ganapati Muni, the devotee who recorded Sri Ramana Gita, had a photographic memory, and Bhagavan has gone on record as saying that the teachings recorded there are an accurate presentation of the conversations that took place. However, he was not so happy with the questions themselves or with the motives that lay behind them.

Around 1980 Sadhu Om interviewed Sadhu Natanananda about various events that had taken place during Bhagavan’s lifetime and the conversation was recorded on an audio tape. Sadhu Om and Michael James made an English translation of this conversation shortly afterwards, and Michael was kind enough to give me a copy.

Sadhu Natanananda said during the interview that shortly after he had arrived at Ramanasramam he had asked Bhagavan about the contents of Sri Ramana Gita because he didn’t read Sanskrit himself. Bhagavan told him that he didn’t need to read the text.

Then Bhagavan told him, ‘They came to me, not to get knowledge of my teachings, but to convert me to their own. They tried to get me to agree with them, but I refused. Even though I wouldn’t say what they wanted me to say, they went ahead and published the book. This is a bit like a high-wire circus artist who falls off the wire, does a somersault on the way down to the safety net, and then pretends that falling off was all part of the act.’

This is harsh criticism indeed, but it didn’t stop Bhagavan from doing his usual thorough job of editing and translating the editions of this book that came out in the last few decades of his life. The book was popular with many devotees and Bhagavan took great care to ensure that all editions of it were accurate and well translated.

Next, I must mention a little-known book that Bhagavan was actively involved in. In the late 1920s he asked Lakshmana Sarma if he had read Ulladu Narpadu. Lakshmana Sarma replied that he hadn’t, adding that the Tamil in the verses was too complicated for him. Lakshmana Sarma knew Sanskrit and had a good grounding in Vedanta, but he hadn’t studied the literary Tamil format in which Bhagavan had composed Ulladu Narpadu. Bhagavan invited Lakshmana Sarma to come every day and have lessons on the meaning of each verse. After each verse was completed, Lakshmana Sarma would compose a Sanskrit rendering of that verse to prove that he had fully understood the meaning. Bhagavan checked these Sanskrit verses and usually made him change them several times until he was satisfied that the meaning had been accurately conveyed. Lakshmana Sarma’s Sanskrit rendering of Ulladu Narpadu was eventually published under the title Revelation, and an English translation of it, by Lakshmana Sarma himself, is also available from Sri Ramanasramam. Other than Muruganar, Lakshmana Sarma was the only devotee to have private lessons from Bhagavan on the meanings of his written works.

In the early 1930s Lakshmana Sarma used the knowledge he had gained from these lessons with Bhagavan to write a Tamil commentary on Ulladu Narpadu. This commentary was serialised in a Tamil magazine. Bhagavan cut them all out of the magazine and pasted them in a scrapbook that was kept near his sofa. If people approached him and asked him for the meaning of any particular verse, he would often hand over the scrapbook and ask them to read the relevant entry. Chinnaswami, the manager of Ramanasramam, refused to publish this work as an ashram book because he had had some other dispute with Lakshmana Sarma, so Lakshmana Sarma published it himself. Bhagavan was not happy with this arrangement. Usually, he never interfered with the administration of the ashram, but in this case he decided to make an exception. He went to the ashram office and told Chinnaswami, ‘Everyone is saying that this is the best book on Ulladu Narpadu. Why don’t you print it?’

Chinnaswami took the hint and subsequent editions were printed by the ashram. A few years ago a translation of the book was serialised in The Mountain Path, and once the serialisation had been completed, the whole work was published by Sri Ramanasramam.

I should like to put the spotlight now on Talks With Sri Ramana Maharshi, the biggest published collection of dialogues with Bhagavan. The first thing to note is that Bhagavan never checked and revised this book in the way that he did with Guru Vachaka Kovai or the other books of conversations that appeared during his lifetime. A portion of the original manuscript, recorded by Munagala Venkataramiah in the 1930s, still exists. There are various editing and correction marks in it done by devotees of that era, but none of the marks is by Bhagavan. Annamalai Swami and Sadhu Om both told me that they saw Bhagavan reading parts of the manuscript in the hall, but at no point did he make any attempt to edit or change what was there.

There are several factors that need to be weighed when one is assessing the reliability of what appears in this book:

(a) No one ever recorded Bhagavan’s voice. All the dialogues that appear were written down from memory.

(b) Munagala Venkataramiah was not always allowed to write down what Bhagavan said at the time he said it. For some time Chinnaswami enforced a rule that no one was allowed to take any notes in the hall. During these periods Munagala Venkataramiah had to wait till he got back to his room, often several hours later, before he could commit his memories of conversations to paper.

(c) Munagala Venkataramiah had a reputation for adding comments of his own when he acted as Bhagavan’s translator in the hall. Some of these additional comments found their way into his manuscript.

(d) Munagala Venkataramiah was not the sole recorder. Visitors who had had conversations with Bhagavan when Munagala Venkataramiah was absent sometimes wrote up their own versions of these conversations and passed them on to Munagala Venkataramiah. These contributions can only be as reliable as the people who made them. Munagala Venkataramiah sometimes edited these contributions, and sometimes incorporated them without changes. Talk numbers 530-47, for example, were recorded by Annamalai Swami in his own diary. Munagala Venkataramiah heavily edited many of these entries.

(e) Other people such as S. S. Cohen, who were also recording dialogues during this period, sometimes have quite different versions of the same conversation.