The following brief summary of Sri Ramana Maharshi’s life and teachings has been taken from the introduction to ‘Living by the Words of Bhagavan’. A more detailed account can be found here:

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi is widely acknowledged as being one of the outstanding Indian Gurus of modern times. In 1896, while he was still a sixteen-year-old schoolboy, he realised the Self during a dramatic death experience that lasted about twenty minutes. Since he had had no previous exposure to spiritual thought or practice, he initially found the experience rather perplexing. In the first few weeks after his realisation he alternately thought that he had either been taken over by a spirit or afflicted by a strange but rather pleasant disease. He told no one about the experience and tried to carry on living the life of a normal South Indian schoolboy. In the days that followed he succeeded with his pretence, but after about six weeks he became so disenchanted with the mundane trivia of school and family life, he decided to leave home and find a place where he could rest quietly in his experience of the Self without having any untoward interruptions or distractions.

He elected to go to Arunachala, a famous holy mountain located about 120 miles south-west of Madras. The choice was far from random: in his early years he had always felt a sense of awe when the name Arunachala was mentioned. In fact, before his misapprehension was corrected by a relative, he had thought that Arunachala was some heavenly realm rather than an earth-bound pilgrimage centre that could be reached by public transport. In later years he would tell people that Arunachala was his Guru, and sometimes he would also say that it was the power of Arunachala which had brought about his realisation and had subsequently drawn him to its physical form.

The young Ramana Maharshi took great pains to ensure that no one in his family knew where he was going. He left his home secretly and arrived at Arunachala, after a rather adventurous journey, three days later. He spent the remaining fifty-four years of his life on or near the holy mountain, refusing to leave it even for a day.

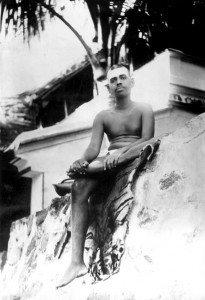

On his first day there he threw away all his money and possessions except for a loincloth, shaved his head as a sign of spiritual renunciation, and found a quiet place in the precincts of the main Arunachala temple where he could sit undisturbed. In the four or five years that followed he spent nearly all his time sitting with his eyes closed in various temples and shrines, completely absorbed in an overwhelming awareness of the Self. He was occasionally fed by a sympathetic visitor or pilgrim, and later by a regular attendant, but, except for one short period when he went out begging for his food, he displayed no interest in his bodily welfare or in the events of the world that were going on around him.

In 1901 he moved to Virupaksha Cave, situated about 300 feet up the mountain behind the main temple, and remained there for most of the next fourteen years. As time went by he began to show a little interest in the visitors who came to see him but he rarely spoke. He was still content to spend most of each day sitting in silence or wandering around on the slopes of Arunachala. He had begun to attract devotees while he was still sitting motionless in the temple. By the time he moved to Virupaksha Cave he already had a small group of followers who were occasionally supplemented by visiting pilgrims.

There is a Sanskrit word, tapas, which means an intense spiritual practice, accompanied by physical self-denial or even bodily mortification, through which one’s spiritual impurities are systematically burnt off. Some people were attracted to him because they felt that a man who had performed such intense tapas (in his early years in the temple he often sat for days without moving) must have acquired great spiritual power. Others were attracted to him because they felt a palpable radiance of love and joy emanating from his physical form.

Ramana Maharshi made it clear in later years that he had not been doing any form of tapas or meditation in his early years at Arunachala. If he was ever asked about this he would say that his Self-realisation had occurred during the death experience in his family’s house in 1896 and that his subsequent years of silent, motionless sitting were merely a response to an inner urge to remain completely absorbed in the experience of the Self.

In his last few years at Virupaksha Cave he began to talk to visitors and answer their spiritual queries. He had never been completely silent but in his early years at Arunachala his words had been few and far between. The teachings he gave out came from his own inner experience of the Self, rather than from book knowledge. When he did speak, he generally utilised the structures and vocabulary of Advaita Vedanta, an ancient and well-regarded school of Indian philosophy which maintains that the Self (Atman) or Brahman is the only existing reality and that all phenomena are indivisible manifestations or appearances within it. The ultimate aim of life according to both Ramana Maharshi and earlier advaita teachers is to transcend the illusion that one is an individual person who functions through a body and a mind in a world of separate, interacting objects. Once this has been achieved one becomes aware of what one really is: the Self, which is immanent, formless consciousness.

Ramana Maharshi’s family had managed to track him down in the 1890s but he had refused to return to the family home. In 1914 his mother decided to go and live with her son at Arunachala and spend her remaining years with him. In 1915 he, his mother and the group of devotees who resided at Virupaksha Cave, moved further up the hill to Skandashram, a little ashram which had been built specially for him by one of his early devotees.

Prior to this time the devotees who were living with Ramana Maharshi had gone begging in the local town for their food. Hindu religious renunciants, called sadhus or sannyasins, often support themselves in this way. Mendicant monks have always been part of the Hindu tradition and no stigma is attached to those who beg for religious reasons. When Bhagavan (I shall mostly call him by this title in future since this is how he was addressed by nearly all his devotees) moved to Skandashram, his mother began to cook regular meals for all the people who lived there. She soon became an ardent devotee of her son and made such rapid spiritual progress that, with the aid of Bhagavan’s grace and power, she was able to realise the Self at the moment of her death in 1922.

Her body was buried on the plain that bordered the southern side of Arunachala. A few months later Bhagavan, prompted by what he later called ‘the divine will’, left Skandashram and went to live next to the small shrine which had been erected over her body. In the years that followed a large ashram grew up around him. Visitors from all over India, and later from abroad, came to see him to ask his advice, to seek his blessings or merely to bask in his peace-giving radiance. By the time he passed away in 1950 at the age of seventy he had become something of a national institution – a physical embodiment of all the finer points of a Hindu tradition that stretched back thousands of years.

His fame and his attractive power did not derive from any miracles he performed. He exhibited no special powers and poured scorn on those who did. Nor did his fame derive to any great extent from his teachings. It is true that he extolled the virtues of a hitherto little-known spiritual practice, but it is also true that most other aspects of his teachings had been taught by generations of Gurus before him. What caught the minds and the hearts of his visitors was the impression of saintliness that one immediately felt in his presence. He led a simple austere life; he gave equal respect and consideration to all devotees who approached him for help; and, perhaps most importantly, he effortlessly radiated a power which was perceived by all those who were near him as a feeling of peace or well-being. In Bhagavan’s presence, awareness of being an individual person was often replaced by a full awareness of the immanent Self.

Bhagavan made no attempt to generate this energy, nor did he make any conscious effort to transform the people around him. The transmission of the power was spontaneous, effortless and continuous. If transformations took place because of it, they came about because of the receiver’s state of mind, not through any of Bhagavan’s decisions, desires or actions.

Bhagavan was fully aware of these radiations and he frequently said that the transmission of this energy was the most important and the most direct part of his teachings. The verbal and written teachings he gave out and the various meditation techniques he endorsed were all, he said, only for those who were unable to remain attuned to the flow of grace that was constantly emanating from him.