Maharaj initially didn’t seem to agree with the remarks that had been attributed to him in the book, but then he added, ‘The words must be true because Maurice wrote them. Maurice was a jnani, and the jnani’s words are always the words of truth.’

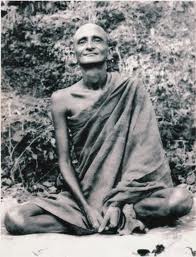

I have met several people who knew Maurice, and all of them have extraordinary stories to tell about him. He visited Swami Ramdas in the 1930s and Ramdas apparently told him that this would be his final birth.

That comment was recorded in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi in the late 1930s, decades before he had his meetings with Maharaj. He was at various stages of his life a follower of Ramana Maharshi, Gandhi, and J. Krishnamurti.

While he was a Gandhian he went to work for the raja of a small principality and somehow persuaded him to abdicate and hand over all his authority to people he had formerly ruled as an absolute monarch. His whole life is full of astonishing incidents such as these that are virtually unknown. I have been told by someone who used to be a senior Indian government official in the 1960s that it was Frydman who persuaded the then India Prime Minister Nehru to allow the Dalai Lama and the other exiled Tibetans to stay in India. Frydman apparently pestered him continuously for months until he finally gave his consent. None of these activities were ever publicly acknowledged because Frydman disliked publicity of any kind and always tried to do his work anonymously.

Harriet: What were Frydman’s relations with Ramana Maharshi like? Did he leave a record?

David: There are not many stories in the Ramanasramam books, and in the few incidents that do have Maurice’s name attached to them, Ramana is telling him off, usually for trying to give him special treatment. In an article that Maurice wrote very late in his life, he lamented the fact that he didn’t fully appreciate and make use of Bhagavan’s teachings and presence while he was alive.

However, he did use his extraordinary intellect and editing skills to bring out Maharshi’s Gospel in 1939. This is one of the most important collections of dialogues between Bhagavan and his devotees. The second half of the book contains Frydman’s questions and Bhagavan’s replies to them. The quality of the questioning and the editing is quite extraordinary.

A few hundred years ago a French mathematician set a difficult problem and challenged anyone to solve it. Isaac Newton solved it quickly and elegantly and sent off the solution anonymously. The French mathematician immediately recognized that Newton was the author and apparently said, ‘A lion is recognised by his claws’.

I would make the same comments about the second half of Maharshi’s Gospel. Though Frydman’s name has never appeared on any of the editions of the book, I am absolutely certain that he was the editor and the questioner.

Harriet: So far as you are aware Maharaj never publicly acknowledged anyone else’s enlightenment?

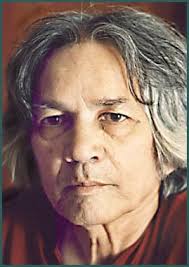

David: There may have been others but the only other one I know about, since I witnessed it first-hand, was a Canadian – at least I think he was Canadian – called Rudi. I had listened to some tapes before I first went to Maharaj and this man Rudi featured prominently on them. I have to say that he sounded utterly obnoxious. He was pushy, argumentative and aggressive; apparently Maharaj threw him out on several occasions. I had never met Rudi; I only knew him from the tapes I had heard.

Then one day Maharaj announced, ‘We have a jnani coming to visit us this morning. His name is Rudi.’

I laughed because I assumed that Maharaj was making fun of his pretensions to enlightenment. Maharaj could be quite scathing about people who claimed to be enlightened, but who weren’t. Wolter Keers, a Dutch advaita teacher, was someone who fell into that category. Every so often he would come to Bombay to see Maharaj, and on every visit Maharaj would tell him off for claiming to be enlightened when he wasn’t. On one visit he started lecturing Wolter before he had even properly entered the room. There was a wooden stairway that led directly into the room where Maharaj taught. As Wolter’s head appeared above the top step, Maharaj suspended his other business and started laying into him.

‘You are not enlightened! How dare you teach in the West, claiming that you are enlightened?’

On one of my other visits Wolter was due to arrive and Maharaj kept asking when he was going to appear.

‘Where is he? I want to shout at him again. When is he going to arrive?’

On that particular visit I had to leave before Wolter came so I don’t know what form the lecture took, but I suspect that it was a typically hot one.

Anyway, let’s get back to Rudi. When Maharaj announced that a ‘jnani’ was due, I assumed that Rudi was going to get the Wolter treatment. However, much to my amazement, Maharaj treated him as the genuine article when he finally showed up.

After spending a good portion of the morning wondering when Rudi was going to appear, Maharaj then asked him why he had bothered to come at all.

‘To pay my respects to you and to thank you for what you have done for me. I am leaving for Canada and I came to say goodbye.’

Maharaj didn’t accept this explanation: ‘If you have come to this room, you must have some doubt left in you. If you were doubt-free, you wouldn’t bother to come at all. I never visit any other teachers or Gurus because I no longer have any doubts about who I am. I don’t need to go anywhere. Many people come to me and say, “You must visit this or that teacher. They are wonderful,” but I never go because there is nothing I need from anyone. To come here you must either want something you haven’t already got or have a doubt of some sort. Why have you come?’

Rudi repeated his original story and then kept quiet. I was looking at him and he seemed to me to be a man who was in some inner state of ecstasy or bliss that was so compelling, he found it hard even to speak. I still wasn’t sure whether Maharaj was accepting his credentials, but then the woman he had arrived with asked Maharaj a question.

Maharaj replied, ‘Ask your friend later. He is a jnani. He will give you correct answers. Keep quiet this morning. I want to talk to him.’

It was at this point that I realised that Maharaj really did accept that this man had realised the Self.

Rudi then asked Maharaj for advice on what he should do when he returned to Canada. I thought that it was a perfectly appropriate question for a disciple to ask a Guru on such an occasion, but Maharaj seemed to take great exception to it.

‘How can you ask a question like that if you are in the state of the Self? Don’t you know that you don’t have any choice about what you do or don’t do?’

Rudi kept quiet. I got the feeling that Maharaj was trying to provoke him into a quarrel or an argument, and that Rudi was refusing to take the bait.

At some point Maharaj asked him, ‘Have you witnessed your own death?’ and Rudi replied ‘No’.

Maharaj then launched into a mini-lecture on how it was necessary to witness one’s own death in order for there to be full realisation of the Self. He said that it had happened to him after he thought that he had fully realised the Self, and it wasn’t until after this death experience that he understood that this process was necessary for final liberation. I hope somebody recorded this dialogue on tape because I am depending on a twenty-five-year-old memory for this. It seems to be a crucial part of Maharaj’s experience and teachings but I never heard him mention it on any other occasion. I have also not come across it in any of his books.

Maharaj continued to pester Rudi about the necessity of witnessing death, but Rudi kept quiet and just smiled beatifically. He refused to defend himself, and he refused to be provoked. Anyway, I don’t think he was in any condition to start and sustain an argument. Whatever state he was in seemed to be compelling all his attention. I got the feeling that he found articulating even brief replies hard work.

Finally, Rudi addressed the question and said, ‘Why are you getting so excited about something that doesn’t exist?’

I assumed he meant that death was unreal, and as such, was not worth quarrelling about.

Maharaj laughed, accepted the answer and gave up trying to harass him.

‘Have you ever had a teacher like me?’ demanded Maharaj, with a grin.

‘No,’ replied Rudi, ‘and have you ever had a disciple like me?’

They both laughed and the dialogue came to an end. I have no idea what happened to Rudi. He left and I never heard anything more about him. As they say at the end of fairy stories, he probably lived happily ever after.

Harriet: You say that Maharaj never visited other teachers because he no longer had any doubts. Did he ever talk about other teachers and say what he thought of them?

David: He seemed to like J. Krishnamurti. He had apparently seen him walking on the streets of Bombay many years before. I don’t think that Krishnamurti noticed him. Afterwards, Maharaj always spoke well of Krishnamurti and he even encouraged people to go and see him. One day Maharaj took a holiday and told everyone to go and listen to Krishnamurti instead. That, I think, shows a high level of approval.

The most infamous teacher of the late 1970s was Osho, or Rajneesh as he was in those days. I once heard Maharaj say that he respected the state that Rajneesh was in, but he couldn’t understand all the instructions he was giving to all the thousands of foreigners who were then coming to India to see him. Although the subject only came up a couple of times while I was there, I got the feeling he liked the teacher but not the teachings. When Rajneesh’s foreign ‘sannyasins’ showed up in their robes, he generally gave them a really hard time. I watched him throw quite a few of them out, and I saw him shout at some of them before they had even managed to get into his room.

I heard a story that he also encountered U. G. Krishnamurti in Bombay. I will tell you the version I heard and you can make up your own mind about it. It was told to me by someone who spent a lot of time with U. G. in the 1970s.

It seems that Maurice Frydman knew U. G. and also knew that he and Maharaj had never met, and probably didn’t know about each other. He wanted to test the theory that one jnani can spot another jnani by putting them both in the same room, with a few other people around as camouflage. He organised a function and invited both of them to attend. U. G. spent quite some time there, but Maharaj only came for a few minutes and then left.

After Maharaj had left Maurice went up to U. G. and said, ‘Did you see that old man who came in for a few minutes. Did you notice anything special? What did you see?’

U. G. replied, ‘I saw a man, Maurice, but the important thing is, what did you see?’

The next day Maurice went to see Maharaj and asked, ‘Did you see that man I invited yesterday?’

A brief description of what he looked like and where he was standing followed.

Then Maurice asked, ‘What did you see?’

Maharaj replied, ‘I saw a man Maurice, but the important thing is, what did you see?’

It’s an amusing story and I pass it on as I heard it, but I should say that U. G.’s accounts of his meetings with famous teachers sometimes don’t ring true to me. I have heard and read his accounts of his meetings with both Ramana Maharshi and Papaji, and in both accounts Bhagavan and Papaji are made to do and say things that to me are completely out of character.

When Maharaj told Rudi that he had no interest in visiting other teachers, it was a very true statement. He refused all invitations to go and check out other Gurus. Mullarpathan, one of the translators, was a bit of a Guru-hopper in the 1970s, and he was always bringing reports of new teachers to Maharaj, but he could never persuade him to go and look at them. So, reports of meetings between Maharaj and other teachers are not common. Papaji ended up visiting Maharaj and had a very good meeting with him. In his biography he gives the impression that he only went there once, but I heard from people in Bombay that Papaji would often take his devotees there. He visited quite a few teachers in the 1970s, often when he was accompanying foreigners who had come to India for the first time. It was his version of showing them the sights. They would never ask questions; they would just sit quietly and watch what was going on.