I have an embarrassing memory of another time he got angry with me. One afternoon my attention was wandering and my mind was embroiled in some larger-than-life ego fantasy. I was off in my own little world, not really listening to what was going on. Maharaj stopped the answer he was giving to someone else, apparently in mid-sentence, turned to me and started shouting at me, demanding to know whether I was listening and understanding what he was saying. I did a little prostration as an apology and put my attention back on what he was talking about. Afterwards, a few people wanted to know why he had suddenly launched such a ferocious attack on me. So far as they were concerned I was just sitting there minding my own business. I definitely deserved that one, though. In retrospect I can say that it increased both my attentiveness and my faith in him. When you know that the teacher in front of you is continuously monitoring all your thoughts and feelings, it makes you clean up your mental act quite a bit.

On another occasion Maharaj got angry with me simply because one of the translators didn’t understand what I had asked. I said that the previous day he had said one thing, whereas this morning he was saying what appeared to be the exact opposite. The translator somehow assumed I was criticising the quality of the translation on the previous day and passed on my critique to Maharaj. He really got angry with me over that, but that one just bounced off me because I realised immediately that it was all due to a misunderstanding. Someone eventually told the translator what I had actually said, and he apologised for all the trouble his comments had caused.

Harriet: Were the translators all good? I have been told that some were better than others.

David: Yes, there were good ones and not-so-good ones. I think everyone knew who was good and who was not, but that didn’t result in the good ones being called on to do the work if they happened to be there. There seemed to be some process of seniority at work. The translators who had been there the longest were called on first, irrespective of ability, and those who might have done a better job would have to wait until these more senior devotees were absent. When I first went a man called Sapre did most of the morning translations. He was very fluent and seemed to have a good grasp of Maharaj’s teachings, but he interpolated a lot of his own stuff in his English answers. Two sentences from Maharaj might turn into a two-minute speech from Sapre. Even though most of us didn’t know any Marathi, we knew that he must be making up a lot of his stuff simply because he was talking for so long. Several people complained to Maharaj about this, but he always supported Sapre and generally got angry with the people who complained about him. That was the cause of the outburst I just mentioned. Maharaj thought I was yet another person complaining about Sapre’s translations.

Mullarpathan was next down the pecking order. I liked him because he was very literal. Possibly not quite as fluent as some of the others, but he scored points with me because he stuck to the script both ways. I once asked Maharaj a question through him, and when the answer came back, it made absolutely no sense at all. Mullarpathan, though, was beaming at me as if he had just delivered some great pearl of wisdom.

I thought about it again and it still made no sense, so I said, somewhat apologetically, ‘I don’t understand any of that answer. It doesn’t make any sense to me at all.’

‘I know,’ replied Mullarpathan, ‘it didn’t make any sense to me either. But that’s what Maharaj said and that’s what I translated.’

Somewhat relieved, I asked him to tell Maharaj that neither of us had understood what he had said and requested him to explain the topic a little differently. Then we got on with the conversation.

I really respected Mullarpathan for this. He didn’t try to put some sense into the answer, and he didn’t tell Maharaj that his answer didn’t make any sense. He just translated the words for me in a literal way because those were the words that Maharaj had intended me to hear.

Right at the bottom, in terms of seniority anyway, was Ramesh Balsekar. He didn’t come to see Maharaj until some point in 1978. I thought this was unfortunate because in my opinion, and in the opinion of many of the other foreigners there, he was by far the most skilful of all the translators. He had a good understanding of the way foreign minds worked and expressed themselves, and a good enough intellect and memory to remember and translate a five-minute rambling monologue from a visitor. He was so obviously the best, many of us would wait until it was his turn to translate. That meant there were occasionally some long, embarrassing silences when the other translators were on duty. Everyone was waiting for them to be absent so that Balsekar could translate for them.

All the translators had their own distinctive style and their own distinctive phrases. When I read Jean Dunne’s books in the 1980s I was transported back into Maharaj’s room because I would be hearing the words, not just reading them. I would look at a couple of lines, recognise Mullarpathan’s style, or whoever else it happened to be, and from then on I would hear the words in my mind as if they were coming out of the translators’ mouths.

Harriet: So all these books are simply a transcription of what the interpreter said on the day of the talk. They are not translations of the original Marathi?

David: I don’t know about the other books, but I know that’s what Jean did. For a couple of weeks I spent the afternoon in her flat, which was near Chowpatthy Beach. On that particular visit, my own place was too far away, so I just slept there at night. Jean was doing transcriptions for Seeds of Consciousness at the time and she would occasionally ask for my help in understanding difficult words on the tape, or she would ask for an opinion on whether a particular dialogue was worth including. I know from watching her work and from reading her books later that she was working with the interpreter’s words only.

Harriet: Did she ask Maharaj if she could do this work? How did she get this job?

David: From what I remember, it was the other way round. He asked her to start doing the work. This created a bit of resentment amongst some of the Marathi devotees, some of whom thought they had the rights to Maharaj’s words. There was an organisation, a Kendra that had been set up in his name to promote him and his teachings, and certain members seemed a bit miffed that they had been left out of this decision. One of them came to the morning session and actually said to Maharaj that he (i.e. the visitor) alone had the right to publish Maharaj’s words because he was the person in the Kendra who was responsible for such things. I thought that this was an absurd position to take: if you set up an organisation to promote the teachings of your Guru, and your Guru then appoints someone to bring out a book of his teachings, the organisation should try to help not hinder the publication. Maharaj saw things the same way.

In his usual blunt way he said, ‘I decide who publishes my teachings, not you. It’s nothing to do with you. I have appointed this woman to do the job and you have no authority to veto that decision.’

The man left and I never saw him again.

Harriet: Did you never feel tempted to write about Maharaj yourself? You seem to have written about all the other teachers you have been with.

David: On one of my early visits Maharaj asked me what work I did at Ramanasramam. I told him that I looked after the ashram’s library and that I also did some book reviewing for the ashram’s magazine.

He gave me a strong look and said, ‘Why don’t you write about the teachings?’

I remember being a little surprised at the time because at that point of my life I hadn’t written a single word about Ramana Maharshi or any other teacher. And what is more, I had never felt any interest or inclination in doing so. Maharaj was the first person to tell me that this was what I should be doing with my life.

As for writing about Maharaj, the opportunity never really arose. In the years that I was visiting him, I wasn’t doing any writing at all, and in the 80s and 90s I had lots of other projects and topics to occupy myself with.

Harriet: You have some good stories to tell, and some interesting interpretations of what you think Maharaj was trying to do with people. I am finding all this interesting, and I am sure other people would if you took the trouble to write it down.

David: Yes, as I have been talking about all these things today, a part of me has been saying, ‘You should write this down’. The feeling has been growing as I have been talking to you. After you leave, maybe I will start and try to see how much I can remember.

Harriet: I suppose we should have talked about this much earlier, but how did you first come to hear of Maharaj, and what initially attracted you to him?

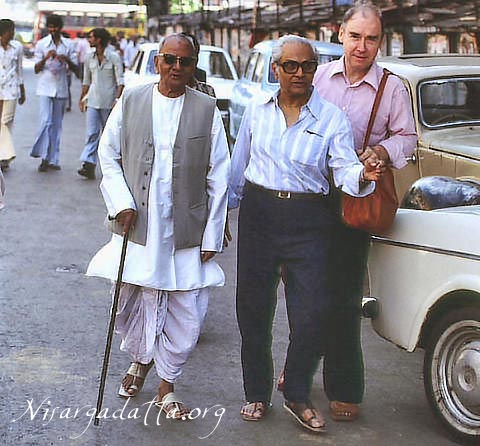

David: Sometime in 1977 I gave a book, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, by Chogyam Trunga, to a friend of mine, Murray Feldman, and said that he would probably enjoy reading it. I knew he had had a background in Buddhism and had done some Tibetan practices, so I assumed he would like it. He responded by giving me a copy of I am That, saying that he was sure that I would enjoy it. Murray had known about Maharaj for years and had even been to see him when Maurice Frydman was a regular visitor.

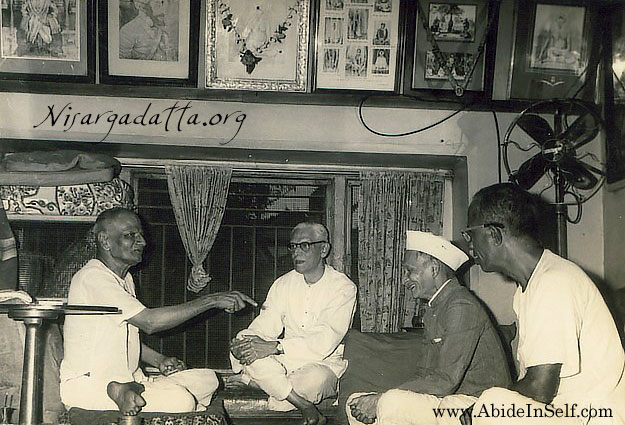

I remember Murray’s vivid description of the two of them together: two old men having intensely animated discussions during which they would both get so heated and excited, they would be having nose-to-nose arguments, with lots of raised voices and arm waving. He had no idea what they were talking about, but he could feel the passion from both sides. In those days, if you visited Maharaj, you were likely to be the only person there. You would get a cup of tea and a very serious one-on-one discussion, with no one else present.

A few years later I heard Maharaj say, ‘I used to have a quiet life, but I am That has turned my house into a railway station platform’.

Anyway, back to the story. I am digressing before I have even started. I went through the book and I have to admit that I had some resistance to many of the things Maharaj said. I was living at Ramanasramam at the time and practicing Bhagavan’s teachings. There were clear similarities between what Maharaj was saying and what Bhagavan had taught, but I kept tripping over the dissimilarities: statements that the ‘I am’ was not ultimately real, for example. However, the book slowly grew on me, and by the end I was hooked. In retrospect I think I would say that the power that was inherent in the words somehow overcame my intellectual resistance to some of the ideas.

I went back to the book again and again. It seemed to draw me to itself, but whenever I picked it up, I found I couldn’t read more than a few pages at a time. It was not that I found it boring, or that I disagreed with what it was saying. Rather, there was a feeling of satisfied satiation whenever I went through a few paragraphs. I would put the book down and let the words roll around inside me for a while. I wasn’t thinking about them or trying to understand them or wondering if I agreed with them. The words were just there, at the forefront of my consciousness, demanding an intense attention.

I think that it was the words and the teachings that initially fascinated me rather than the man himself because in the first few weeks after I read the book I don’t recollect that I had a very strong urge to go to see him. However, all that changed when some of my friends and acquaintances started going to Bombay to sit with him. All of them, without exception, came back with glowing reports. And it wasn’t just their reports that impressed me. Some of them came back looking absolutely transfigured. I remember an American woman called Pat who reappeared radiant, glowing with some inner light, after just a two-week visit.

Papaji used to tell a story about a German girl who went back to Germany and was met by her boyfriend at the airport. The boyfriend, who had never met Papaji and who had never been to India, prostrated full length on the airport floor at her feet.

He told her afterwards, ‘I couldn’t help myself. You have undergone such an obvious illuminating transformation, I felt compelled to do it.’

I know how he felt. I never prostrated to any of the people who had come back from Bombay, but I could recognise the radical transformations that many of them had undergone. Even so, I think it was several months before I decided to go and see for myself what was going on in Bombay.