Tiruvadavur Adigal Puranam

This is a biography of the Tamil saint Manikkavachagar whose devotional hymns, collected in the Tiruvachagam, are a classic of Tamil devotional literature. There are two principal sources for biographical information: four chapters in the Tiruvilaiyadal Puranam (a work that chronicles the divine acts of Siva in Chidambaram) and the Tirvadavur Adigal Puranam, a much later work that expands on the original text. In this new translation, which includes the full text of Tiruvadavur Adigal Puranam, Robert Butler utilises all the available sources to reconstruct Manikkavachagar’s life, his beliefs and his world view. The book also contains key translations from the Tiruvachagam.

This is how I introduced Manikkavachagar in a long article that was jointly written and translated by T. V. Venkatasubramanian, Robert Butler and myself:

In the seventh to ninth centuries AD there appeared in South India an upsurge of devotional fervour that completely transformed the religious inclinations and practices of the region. Vaishnava and Saiva bhaktas became infused with a religious spirit that emphasised ecstatic devotion to a personal deity rather than the more sober rites and rituals of vedic Brahmanism. It was both a populist Hindu revolt, since it expressed the people’s dissatisfaction with the hierarchies of caste, and a demonstration of contempt for the alien philosophies of Jainism and Buddhism, which had by then permeated large areas of South India.

The movement’s leaders were the various saints who toured the countryside singing songs in praise of their personal God. The language of these songs was deliberately simple, for they were intended to be sung by ordinary devotees, either alone or in groups. While it is true that the deities addressed were ones such as Vishnu and Siva, who were prominent components of the North Indian pantheon, the mode of expression and the philosophical content of the poems were unique, being an expression of the indigenous Tamil spirit and culture. This was the first of the great bhakti movements that were to invigorate the Hindu tradition throughout India in the succeeding centuries. It was so successful in transforming the hearts and minds of the South Indian population, one commentator has gone so far as to say that these poet-saints ‘sang Buddhism and Jainism out of South India’. (Hymns to the Dancing Siva, by Glen Yocum, 1982 ed., p. 40)

The Saiva revival of this era owed much to four poet-saints who are often collectively referred to as ‘the four’ (Nalvar). Appar, the first to emerge, flourished from the end of the sixth century until the middle of the seventh. Tirujnanasambandhar, the next to appear, was a younger contemporary of his. They were followed by Sundaramurti (end of the seventh century until the beginning of the eighth) and Manikkavachagar, whom most people believe lived in the ninth century.

The spontaneous songs of these early Saiva saints were eventually collected and recorded in a series of books called the Tirumurais. The first seven (there are twelve in all) are devoted exclusively to the songs of Tirujnanasambandhar, Appar, and Sundaramurti, which are known as the Tevarams, while the eighth contains Manikkavachagar’s two extant works. These twelve Tirumurais, along with the later Meykanda Sastras, became the canonical works of the southern Saiva branch of Hinduism. This system of beliefs and practices is still the most prevalent form of religion in Tamil Nadu.

Bhagavan was a huge admirer of Manikkavachagar’s devotional poetry and cited it frequently when he was responding to questions. All of the poetry he cited and commented on has been translated in the article I referenced earlier.

I mentioned in the Ozhivil Odukkam section that Suri Nagamma, the recorder of Letters from Sri Ramanasramam, was a Telugu lady who was not familiar with ancient Tamil texts and saints. When she once professed to Sri Ramana that she was unfamiliar with Manikkavachagar’s biography, Bhagavan gave her this summary of the significant early incidents:

Manikkavachagar was born in a village called Vaadavur (Vaatapuri) in Pandya Desha. Because of that people used to call him Vaadavurar [The man from Vaadavur]. He was put to school very early. He read all the religious books, absorbed the lessons therein, and became noted for his devotion to Siva, as also his kindness to living beings. Having heard about him, the Pandya king sent for him and made him his prime minister and conferred on him the title of Thennavan Brahmarayan, i.e., ‘Premier among Brahmins of the South’. Though he performed the duties of a minister with tact and integrity, he had no desire for material happiness. His mind was always absorbed in spiritual matters. Feeling convinced that for the attainment of jnana, the grace of a Guru was essential, he kept on making enquiries about it.

Once the Pandya king ordered the minister to purchase some good horses and bring them to him. As he was already in search of a Guru, Manikkavachagar felt that it was a good opportunity and started with his retinue carrying with him the required amount of gold. As his mind was intensely seeking a Guru, he visited all the temples on the way. While doing so he reached a village called Tirupperundurai. Having realised the maturity of the mind of Manikkavachagar, Parameswara [Siva, had] assumed the form of a schoolteacher and for about a year before that had been teaching poor children in the village seated on a street pial near the temple. He was taking his meal in the house of his pupils every day by turn. He ate only cooked green vegetables. He was anxiously awaiting the arrival of Manikkavachagar. By the time Manikkavachagar actually came, Iswara assumed the shape of a Siddha Purusha [realised soul] with many sannyasis around him and was seated under a kurundai tree within the compound of the temple. Vaadavurar came to the temple, had darshan of the Lord in it, and while going round the temple by way of pradakshina, saw the Siddha Purusha. He was thrilled at the sight, tears welled up in his eyes and his heart jumped with joy. Spontaneously his hands went up his head in salutation and he fell down at the feet of the Guru like an uprooted tree. Then he got up and prayed that he, a humble being, may also be accepted as a disciple. Having come down solely to bestow grace on him, Iswara, by his look, immediately gave him jnana upadesa [initiation into true knowledge]. That upadesa took deep roots in his heart and gave him indescribable happiness. With folded hands and with joyful tears, he went round the Guru by way of pradakshina, offered salutations, stripped himself of all his official dress and ornaments, placed them near the Guru and stood before him with only a kaupina on. As he felt like singing in praise of the Guru, he sang some devotional songs, which were like gems. Iswara was pleased, and addressing him as ‘Manikkavachagar’ [meaning ‘one whose speech is gems’] ordered him to remain there itself worshipping him. Then he vanished. (Letters from and Recollections of Sri Ramanasramam, by Suri Nagamma, pp. 5-7)

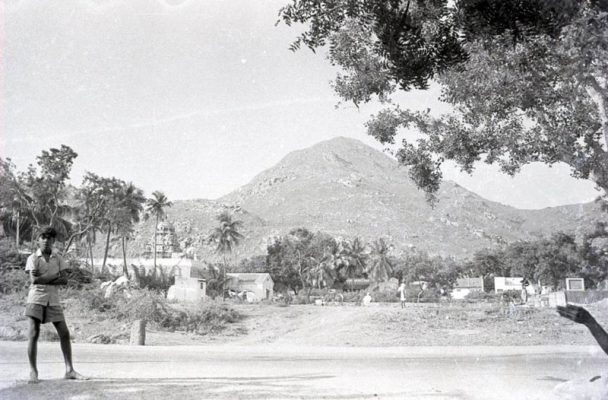

There were many more astonishing and occasionally miraculous incidents, far too many to even summarise here. I will therefore fast-forward the narrative to a point after his liberation when Siva ordered him to tour the Tamil-speaking regions, singing songs in praise of him. One of the places he visited on this grand tour was Tiruvannamalai, which even in the 9th century was a major Saiva pilgrimage centre. Here is Robert’s translation of the portion of the Tiruvadavur Adigal Puranam (‘Tiruvambala Sarukkam’, vv. 376-384) that covers his visit to Tiruvannamalai.

After worshipping at that shrine [Tiru-Venney-Nallur],

with love in his heart he departed,

following the righteous path,

passing through the middle lands,

traversing tall forests and mountains,

where lions and fearsome elephants dwelt,

until he drew near to enduring Arunai’s city.

The ‘middle lands’ are the territories between the Chola and Tondai lands. ‘Arunai’s city’ is Tiruvannamalai. Arunai is an old name that can either refer to the town of Tiruvannamalai or the mountain of Arunachala.

When he saw the palaces and gopurams,

the strong walls, decorated with jewels and pearls,

the great gateways festooned with banners,

towering up in the midst

of a cool densely wooded grove,

in a forest of tall areca trees,

he joyfully made obeisance,

experiencing great bliss.

‘You [Siva] who abide in the form of a mountain [Arunachala]

which appeared on that day as a column of flame

for the two to seek!

Blissful life which fills our hearts!’

Thus did he worship the Supreme Mountain Lord,

receiving His grace, before proceeding forth

to enter Arunai’s prosperous city.

Leaving behind the groves, the city walls,

the streets decorated with many beautiful banners,

and the various shrines of the gods,

and taking the path which led to the holy presence,

he bowed down before the temple of the One

who wears in His locks a kondrai garland,

datura flowers, the moon and the snake,

and then did he perceive the form of Him

who on that day had enslaved him.

This last two lines have been taken by some people to mean that Manikkavachagar had a vision of Siva in the Arunachaleswara Temple. Prof. T. M. P. Mahadevan in his Ten Saints of India (1971 ed., p. 55) has followed this interpretation.

‘Praise be to the dark-throated One

who swallowed the poison halahala

when Brahma, Vishnu and the rest of the gods,

crying out in distress, appealed to Him for protection!

Praise be to the Mountain [Arunachala] of cool ambrosia,

mixed with the milk of green-hued Unnamulai,

which men and gods alike drink down

to cure the overpowering malady of their birth and death!

Unnamulai is the local name of Siva’s consort in Tiruvannamalai.

‘Praise be to the great ocean of grace of Him

who placed His feet upon my head,

the feet which tall Mal could not see,

though he burrowed deep into the earth

in the form of a powerful boar!

Praise be to the Mountain of burnished gold,

at whose side sits the slender

green-hued form of Unnamulai,

who is the earth’s protectress!

‘Praise be to Him who granted His grace

to the victorious Durga,

when She worshipped Him and begged Him

to absolve Her from the sin

of killing the powerful buffalo-headed demon!

Praise be to the beauteous Lord Annamalai,

who came to me on that day and held me in His sway!’

Thus worshipping and praising the Lord

out of heart-felt love,

he dwelt there for some days.

The story of Durga killing the buffalo-headed demon Mahishasura appears in the Arunachala Mahatmyam. The text locates the story in Tiruvannamalai.

It was the month of Margazhi,

when, in the ten days before the ardra asterism,

the beautiful maidens go from household to noble household

calling each other out in the early dawn,

just as the darkness is dispersing,

and, banding together, go to bathe in the holy tank.

The month of Margazhi runs from mid-December to mid-January in the western calendar. In the Hindu calendar there is a cycle of twenty-seven days each month. Each day is named after a particular star. Ardra is one of these star days.

On observing their noble qualities

he sang the immortal hymn ‘Tiruvembavai’

which is composed as if sung by the maidens themselves.

Later, seeing them dance and sing

as they played the pretty game ‘Ammanai’,

he composed the song ‘Ammanai’ in the same manner.

As the final verse in this sequence indicates, Manikkavachagar composed two of the Tiruvachakam poems, ‘Tiruvembavai’ and ‘Ammanai’, on his visit to Tiruvannamalai. There is a tradition in Tiruvannamalai that both poems were composed while Manikkavachagar was doing pradakshina of Arunachala. A small temple on the pradakshina road in the village of Adi-annamalai is supposed to mark the spot where the two poems were composed and sung. Bhagavan confirmed the validity of this tradition when he told Suri Nagamma: ‘He [Manikkavachagar] then stood at that particular place and addressing Arunagiri [Arunachala] sang the songs “Tiruvembavai” and “Ammanai”.’ (Letters from and Recollections of Sri Ramanasramam, by Suri Nagamma, 1992 ed., p. 2)

Robert’s translation and commentary on the ‘Tiruvembavai’ poem can be found here, page 75.

The climax to Manikkavachagar’s life came when Siva visited him in Chidambaram, in disguise, and asked him to dictate all his devotional poetry. Up till then, none of it had been written down. Siva then took the manuscripts and left them in the inner shrine of the Chidambaram Temple at a time when the temple was locked. Manikkavachagar’s name was listed as the author. The priest who found them recognised that a divine miracle of some sort had taken place. Along with a deputation of fellow priests he visited Manikkavachagar and asked him to explain what had happened. Manikkavachagar, realising that Siva had been the visitor who had asked him to dictate all his works, said he would explain what had happened in the temple itself.

This is Robert’s translation of what transpired inside the temple:

537

With the people of Chidambaram, whose renown is ever unfailing, crowding closely about him, filled with devotion, he reached the Hall of pure gold, wherein God’s grace abides. Saying, ‘He it is who is the meaning of this worthy Tamil garland,’ he went swiftly into the Hall, and there, even as they all looked on, he disappeared from view.

538

Pointing with his hand, even as his body vanished, and saying, ‘He is the Reality, the one who dwells in Tillai [Chidambaram], girt by rice fields and groves of areca trees,’ Vadavurar [Manikkavachagar] disappeared from view. Thus it was that the Lord who wears as an ornament a great serpent with its expanded hood, showed his true love for his devotee, and took him to himself, even as water mixes with milk.

Manikkavachagar physically vanished, becoming one with Lord Siva inside the inner shrine. This final chapter of Robert’s translation of the Tiruvadavur Adigal Puranam (verses 510-544) is given as an excerpt in the book section of this site.