Other works by Robert Butler

The five books I have just featured and given excerpts from are all available from the Sri Ramanasramam Book Depot and from this site. However, there are several other titles that Robert has translated and published himself which are all available from Lulu, a print-on-demand service that prints and delivers copies of books when customers order them. The Lulu books are available both as hard copies and also as epubs. Robert has a page on Lulu where his translations are featured: http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/hansens. Here are four of the titles that are featured there.

Ulladu Narpadu: The purpose of this book is to enable those with little or no knowledge of Tamil to read one of Sri Ramana Maharshi’s original verse compositions, Ulladu Narpadu, in the original. No prior knowledge of Tamil is required. Grammatical explanations are given in a variety of formats and there is a full Lexicon and Concordance and an Index of Grammar, arranged by subject.

Unthiyar: A prose and verse translation of Upadesha Unthiyar, Bhagavan’s thirty-verse poem that is better own under its Sanskrit title Upadesa Saram. There is a commentary that includes comparisons with other Unthiyar texts composed by Manikkavachagar and Santhalinga Swamigal.

Kurunthogai: This is a collection of 401 Classical Tamil love poems which date from around 2,000 years ago. They have a freshness and universality which is rare in ‘ancient’ classical literature and this translation attempts to reflect that quality. Rather than simply translating them, it endeavours to recreate them in modern, idiomatic English.

Moments of Bliss Revisited: A linguistic analysis of a Tamil interview given by Padma Venkataraman, a Tamil-speaking devotee of Bhagavan who talked about her time with Bhagavan in the 1940s in an interview that appears on Youtube.

Robert has also been involved with French translations of Padamalai and The Fire of Freedom.

Sonasaila Malai

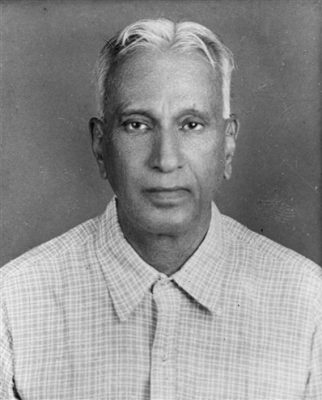

There is one other title by Robert that is available from Lulu: Sonasaila Malai, a Tamil poem about Arunachala that was composed by Sivaprakasha Swamigal, an accomplished Virasaiva poet and scholar who lived in the 17th century, while he was doing a pradakshina of the mountain.

Sivaprakasha Swamigal possessed a vivid and daring poetic imagination that earned him, even during his lifetime, the honorary title of ‘Treasure House of the Imagination’. His evocative imagery can be seen throughout the poem. There are two parts to each of its verses. The first half contains pleas for Siva’s grace, even though the author stresses his unworthiness; the second part contains a visual image in which the nature and attributes of Lord Siva are compared and contrasted with those of the mountain that is Lord Siva’s earthly-manifested form. Sivaprakasha Swamigal places great emphasis on the fact that, unlike the Siva who appears in temples, the mountain of Arunachala is available to everyone, without restrictions of any kind. Each verse concludes with the refrain ‘Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!’ Sonasailam is Arunchala, the embodied form of Siva, while Kailash is the mountain where Siva traditionally dwells. The implication of the refrain is that Arunachala and Siva are eternally one and the same.

Sri Ramana Maharshi appreciated the poem and occasionally cited portions of it. The following passage appears in My Recollections of Bhagavan by Devaraja Mudaliar:

One day Bhagavan quoted the following verse to me from the book called Sona Saila Malai. ‘Arunachala, Lord of Kailas! When Manikkavachakar and others like him sang that they were wanting in Love for you and prayed for the same it was only their modesty and not the truth. But it is the base truth when I say I have no love for you. Pray therefore grant me the same.’

The next day I wanted to copy down this stanza since Bhagavan had quoted it, and nothing he did was without significance. I was going to the library to fetch the book when Bhagavan said to me: ‘You need not go and fetch it. Come here. I know the stanza.’

So saying, he was pleased to take a sheet of paper and write out the stanza for me. It was not unusual for Bhagavan to do such things for some of his close followers. About a score of people may have such writings of Bhagavan in their possession.

It has often been surmised that Ramana Maharshi must have had an eidetic memory, given his ability to memorise extensive passages from works in a number of languages with no apparent effort. Even so the fact that he was able to reproduce this verse from memory in its entirety is a testament to the high regard in which he held it.

Here is Robert’s translation of the verse that Bhagavan had memorized:

6

The sage of Vadavur, whose hymns are rare,

and others too,

they said, ‘We have no love for you!’

but all their weeping and beseeching was a lie.

But when I say ‘I have no love, for you,’

my words are true.

Reveal to me your grace!

The black clouds that the ocean drink

and about you thickly cluster

recall the garment that you made,

from the hide of the elephant you flayed,

its temples oozing, wet

with dark juices of the must,

its trunk like a palmyra [ridged and black].

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

The ‘sage of Vadavur’ was Manikkavachagar, the poet who composed songs of the Tiruvachakam. His home town was Vadavur.

In addition to translating the verses and explaining all the colourful imagery and references that the verses contain, Robert has given a word-for-word translation along with copious linguistic notes. The original Tamil text is also included.

Here is a sample of some of the verses, with Robert’s explanatory notes.

2

In Arur to be born is to gain knowledge

that lies beyond this worldly thrall;

the end of all suffering is to reach

and gaze on Tillai’s holy Hall.

In holy Kasi men joyfully abiding,

await death’s call.

But to the mere thought of your own city

can such as these compare at all?

For those who journey on birth’s ocean

bound for final liberation’s fair shore,

you rise on high

to guide for them the ship of tapas

ending their confusion with a glance.

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

Tillai is the Golden Hall of Chidambaram where Lord Siva, as Nataraja, performs his cosmic dance. Kasi is Benares, nowadays known as Varanasi. Though Kasi is famous for its power to grant liberation to those who die there, the Arunachala Puranam (verse 543) states that is greatness is eclipsed by that of Arunachala.

Even if food were given to ten million great tapasvins in one of the most eminent sthalas [holy places], it would not equal a single grain of boiled rice given in immortal Kasi. [Similarly] if food was given in Kasi to countless crores of great tapasvins, it could not compare to a single grain of boiled rice given in the land of Arunai, [embodiment of] the real.

The first part of this verse echoes a sentiment which has its source in the following sloka which is reputed to be from the Arunachala Mahatmyam, which is itself a section of the Maheshwara Kantam of the Skanda Mahapuraṇam. An identical sentiment occurs in verse 68 of the Tamil Arunachala Puranam:

Liberation [will be assured] in Abhrasadasi [Chidambaram] through seeing [it], in Kamalalaya [Tiru Arur] through birth [there], in Kasi through death [there] [and] at Arunachala through remembrance [of it].

9

Before the Lord of Death,

a flower garland draped

across his mighty chest,

destroys my body’s outward form,

will there be, for wretched me, a day

that your grace comes to wipe away

the ego self that lies within

so that, with every hindrance gone,

I and shining jnana’s form

supreme are one?

With an elephant’s tusk

for a crescent moon,

and bright creepers,

spreading in profusion

like untied tresses

upon your slopes, you shine,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

Before enlightenment the inner body, consisting of the faculties of mind, intellect, will and egoity takes the outward, physical body and its perceptions to be real. It is thus condemned to live out its life in body after body, undergoing innumerable births due to its inability to apprehend its true nature. Once the ego is destroyed there is no longer any obstacle to its uniting with the Lord, its natural state. However, since the mind, however much it desires to be free, is in fact the very obstacle that is preventing that union in the first place, the devotee must surrender to the Lord and make himself a fitting subject for his grace. Jnana, is simply the pure consciousness, the substratum of all being, which is revealed when that which obscures it is removed, that is, when the identification with the body-mind complex is abandoned.

The commentators explain that the bright creeper is a creeping plant that, whilst appearing green by daylight, has a glowing radiance at night. Biologically, it is the climbing staff tree (Celestrus Paniculatus) a climbing shrub found throughout India. The moonlight, catching an elephant’s tusk, and the shining creepers, resembling unloosed braids of hair, offers to the imagination a striking image of Lord Siva with the crescent moon in his untied locks.

11

Upon the broad earth

that the ocean’s fair gown girds about,

quite fittingly you grant your grace

to those who deem the body false.

But to me, who take the body to be true,

will you not deign to grant it too?

Not wishing to dwell within a shrine,

hid from view, and visited

with proper observance of time,

you grant your presence abundantly,

standing fast, for all the world to see,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

The word mey in Tamil means ‘truth’ and also ‘body’, which gives an ironic twist to the phrase ‘deem the body false’. Those who think that mey (body) is poy (false) are right, and I who think that mey (body) is mey (true) am wrong. To those lacking in discrimination, there is nothing more true or real than the body. Only the wise know it to be, in the absolute sense, false. The author, whilst admitting that he does not possess the attainment of the great ones who possess this realisation, makes the point that, as one who labours under this delusion, he is just as much, or more, in need of Siva’s grace in order to dispel it. In the second half of the verse he reinforces his argument by pointing out that Sonasailan, unlike other gods that remain hidden in temples and shrines, is accessible to all without restriction.

13

Will there ever come a day

when you grant your grace,

so that I, poor wretch,

sloughing off the senses’ woes,

and setting up within the fair temple

of my mind your holy feet,

with ankle-rings adorned,

may join the great assembly

of those holy ones who virtue seek?

Men in pradadkshina walk around

with cries that like the ocean’s roar

resound, as in their midst

like holy Mandara you stand and shine

the tapas of the world made manifest,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

In another powerful image the author compares Arunachala to Mount Mandara, which was used as the churning-stick to churn the Milk Ocean, and the press of fervent devotees performing pradakshina around it to the serpent Vasuki, who was employed as the churning rope. The idea is that just as the Puranic churning of the Milk Ocean brought forth the ambrosia which conferred immortality, the throng of devotees performing circuits of Arunachala, calls forth the ambrosia of liberation from birth and death.

14

This mortal frame, that’s bound to die

like bubbles that through water fly,

is truly real, thus did I think.

Whirled through births,

in bliss’ enduring ocean

I knew not how to sink.

Will there ever salvation be

for one so ignorant as me?

With their tusks, the wild pigs root

upon your mountain slopes,

as if the Boar of former times

digging down, still strove today

to reach your beauteous foot,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

When Lord Siva appeared before Brahma and Vishnu as an immeasurable column of fire, Vishnu, as the legend goes, burrowed down in the form of a boar in order to reach its feet and thus prove his superiority over Brahma, who flew up in the form of a swan in order to find its head. The poet imagines that a wild pig that he sees rooting on the slopes of Arunachala is none other than Vishnu himself, still trying to complete his challenge.

17

Will there ever come a day

that, freed from body,

mental faculties and senses five,

with the veil of anavam’s [ego’s]

dark illusion rent,

I see you without seeing,

within myself,

I, a flower, and you the scent?

Flayer of elephant and lion

you came [from Kailash’s Mount],

and now upon your slopes

great herds of these you raise

too numerous to count,

their burning hatred to assuage,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!

Siva wears a tiger skin which belonged to the tiger that the rishis in the Daruka forest conjured up to destroy him, and also a blanket of elephant skin which belonged to the asura Gajasura who attacked him in the form of an elephant. Seeing him come from Kailash dressed in this way, the tigers and elephants of Arunachala would understandably be somewhat aggrieved, and equally understandably, would need to be placated by Siva protecting and nurturing their respective species.

18

For me who languish in the heat

of delusive charms

of pretty girls whose heavy braids

are decked with flower wreaths

where swarms of humming insects feast,

will there ever come a day

that you draw me in, me safe to keep

in the cool shade of your holy feet?

Just as his shining locks do hide

the holy Ganga’s silvery tide

that flows down from his jewelled crown,

white torrents roaring,

tumble down your glittering sides,

Lord Sonasailan! Kailash’s Lord!