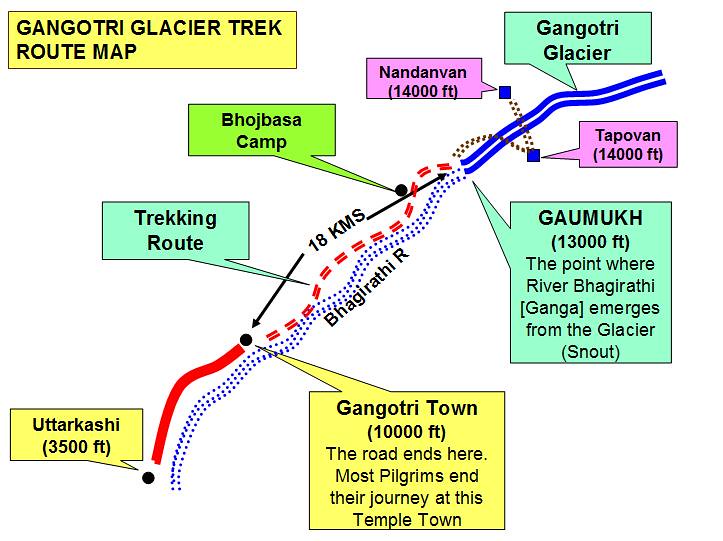

Here is a handy little sketch map I found online:

The road from Rishikesh goes through Uttarkasi and terminates at Gangotri. If you want to travel further upstream from Gangotri, you have to go on foot, following a trail that runs by the side of the river. It is wide enough for mules, but not for wheeled traffic. The river on this map is marked as the’ Bhagirati’. Technically, the Bhagirati only becomes the Ganga further downstream after it meets the Alaknanda River at Devprayag. However, most people regard the source of the Ganga to be the Gangotri Glacier, where the water emerges from the base of the glacier. Gaumukh, the name of the place where the water emerges, means ‘Cow’s mouth’. For many years the front of the glacier did slightly resemble a cow’s head, with the river gushing out of its mouth. Recent ice calving, though, has radically changed the position and contours of the end of the glacier. For example, when I saw it I could tell it was very different from the Gaumukh I had seen on my previous visit more than twenty years before. The town of Gangotri, nowadays about twenty kilometres downstream from Gaumukh, probably started hundreds of years ago when the source of the Ganga was close to the temple that is the central feature of the town.

A couple of days before we were due to walk to Gaumukh and beyond, a huge avalanche wiped out the usual trail and even changed the course of the river close to the front of the glacier. We had to pick our way very gingerly over wobbly boulders on a steep scree slope before we reached the flat elevated plain of Tapovan. A few hardy sadhus have their ashrams there, but most of the visitors are either trekkers or climbers who use the site as a base camp.

Here is the source of the Ganga on the day we visited. The photo was taken from high up on the avalanche that had changed the course of the river. Formerly, the river had flowed in a straight line, downhill from Gaumukh, which is the grey-green pool in the centre of the photo. The avalanche had pushed the river up against the other side of the valley, obliterating the trail on the far side and giving the first kilometre of the river a new ninety-degree bend.

Contrary to popular belief, many glaciers are not white. Their tops are often covered in a thick layer or rocks and gravel, making them look like the spoil heap of an open cast mine. The bottom right photo shows the debris that has accumulated on the top of the Gangotri Glacier’s ice.

The next page is a gallery of photos taken between Gangotri and Tapovan.