There is another analogy which Bhagavan used a lot. He said that in a big wedding feast there are two parties. There is the bride’s party and the bridegroom’s party. It’s quite possible for somebody who has not been invited to the wedding to go there and pretend to be an important guest. In a wedding celebration half the guests are unknown to the other half, and everyone is making an attempt to be nice and hospitable to everyone there. If there is an unknown stranger, the bride’s party will think he is in the groom’s party, and vice versa. The uninvited guest can get away with causing trouble so long as nobody takes the trouble to pin him down and say, ‘Who exactly are you? Which party do you belong to?’

The point of this analogy, according to Bhagavan, is that the ‘I’ thought is neither the Self nor the body. It’s a false entity that comes into existence, superficially appearing to belong either to the body or the Self, but actually belonging to neither. It causes you endless suffering because you never take the trouble to check up on it to see what it is, where it comes from, and what it belongs to.

Sri Ramana said that if you isolate it, watch it, hold on to it, and not let it be distracted by anything whatsoever, it can’t exist any longer. This is the key to understanding why self-enquiry works and why Bhagavan recommended it. He said that the ‘I’ can only continue exist in association with the objects it identifies with. It cannot exist by itself in isolation, free of all thoughts and ideas. There is no such thing as an ‘I’ thought that isn’t holding onto an idea or a perception or a thought or a belief. This is why Bhagavan says that if you sever all of those unwanted accretions from this sense of ‘I’ that you inherently have, that sense of ‘I’ will not be able to subsist independently. It has to go back to its source and disappear. Holding onto that subjective sense of ‘I’, rejecting all possible distractions that take you away from it, immersing oneself in that subjective feeling of ‘I’ as it goes back to its source and disappears – that’s self-enquiry.

People would come to Bhagavan to ask questions about spiritual practice or philosophy. When they asked their questions, he would often reply by saying, ‘Who is asking that question?’ This wasn’t an evasive reply. Sri Ramana taught that the answer to most spiritual, most philosophical questions is a knowledge and an understanding of the ‘I’ who is asking the question. The states and experiences that he was being asked about can only be understood and known when the ‘I’ that is asking about them is extinguished in its source. So, instead of giving an answer which would satisfy an ‘I’ (which he didn’t believe was real or true or had any importance) he would respond by saying, ‘Who is asking that question? Find out the “I” who has asked me that particular question. I’m not going to give you an answer. If you want to find the answer, you have to get the experience of having that ‘I’ disappear and see what remains. That’s the answer to your question.’

This was a bit frustrating for a lot of people They would come with all kinds of fancy philosophical theories and ideas. They’d try and argue with him but he’d just keep coming back again and again with the rejoinder, ‘Who or what is this “I” which is asking me this question?’ In effect he was saying, ‘You’re talking about the content of the mind. I’m talking about the origin of the mind. I’m talking about that which causes the mind to have thoughts, to think thoughts. Go back to the thinker of the thoughts. Find out where it arises from and you’ll get the answer to your question.’

Sri Ramana would say that when a thought arises in your mind, you should ask yourself, ‘To whom does this thought occur?’ This is a way of transferring attention from the object that you’re thinking about to the person, the subject who’s having the thought.

Here is self-enquiry in a nutshell: you have a thought; you have a perception. You note it and then say to yourself, ‘Who has this thought? Who has this perception?’ The only possible answer is ‘I do’. At this point you have suddenly become aware of the ‘I’ which is having the thought. When attention has been transferred in this way from object to subject, Bhagavan then says, ‘Ask yourself “Who am I? Who is this ‘I’ who just had this thought, just had this perception?”’ Don’t try to study or evaluate this ‘I’ in a conceptual way. Simply be aware of it. Exclude all other thoughts and allow it to take you back to the place where it came from.

That’s really all there is to it. Bhagavan said whenever your mind is distracted by the objects you are thinking about, take your attention back to the subject who is having the thought. Either try to see where it comes from by holding onto it until it disappears, or aggressively question it. Enquire into its nature. Enquire into its origin by focusing intently on this sense of ‘I’ and asking, ‘Who am I?’ and see where that leads you.

It’s not rocket science. It’s a simple one-step process. Sri Ramana said that every time your mind is on something else other than the ‘I’, take it back to this ‘I’. Be aware of that ‘I’ intently, vigilantly. Be aware of that subjective feeling of ‘I’ inside yourself. If you get distracted, gently reject the distraction. Don’t try to suppress other thoughts. When you become aware they have caught you again and got you involved in a train of thought, withdraw attention from them and put it instead on the sense of ‘I’, the ‘I’ that was previously indulging in these thoughts. Grip it tightly. If you hold on strongly enough and don’t get distracted, you will discover that it subsides and disappears. Bhagavan said that’s all there is to it, but you have to be vigilant. You have to be attentive. For most people it is hard work, and it needs to go on for a long, long time.

Question: Sometimes Bhagavan says, ‘Ask yourself “Who am I?”’ and sometimes he says, ‘Hold onto the “I” thought’. Is there a difference between these approaches?

David: There are two ways you can approach self-enquiry. Bhagavan said you can either ask yourself ‘Who am I?’ or you can simply be aware of this ‘I’ thought. Sometimes he would tell people ‘Just ask yourself “Who am I?” Find out what is this “I” and where it comes from.’ At other times he would merely say, ‘Hold onto the “I” thought.’

If you check through all the Ramanasramam literature, the replies that have Bhagavan say, ‘Ask yourself “Who am I?”’ – those replies slightly exceed the number of times he said, ‘Hold onto the “I” thought.’ I think the reason this happens is that most of the people who are asking him in the recorded interviews are people who have never done self-enquiry before. They’re coming to him for the first time and asking for advice on a new technique. So, I think he would start them off by getting them to transfer attention from object to subject by saying, ‘Who am I? Who am I?’

But I think most people who have been doing enquiry for a long time find this whole business of saying, ‘To whom does this thought occur?’ ‘To me.’ ‘Who am I?’ a bit of a distraction. Without needing to say all this as a preamble, they very quickly move attention off the object which is distracting them and back to the subject, the perceiver or thinker of the distraction. This is holding onto the ‘I’ without constantly going through the ritual of asking ‘Who am I?’ as a means to redirect attention.

Although I would say that attention to the ‘I’ ultimately is the goal that everyone should aim for, there is one other consideration which personally I think is quite important. Bhagavan instructed devotees to ask themselves ‘Who am I?’ quite clearly, not only in the seminal text Who am I? but also in many of his answers. This means that if you follow his advice with faith, with conviction, then you’ve got the wind behind you. You’ve got Bhagavan’s power, Bhagavan’s grace, helping you to find the source of this ‘I’.

Bhagavan has told you that this what you should do. If you follow his advice to the letter, asking yourself ‘Who am I?’ with the absolute faith and conviction that Bhagavan knows what he’s talking about, that he knows what’s best for you, you will get results. It’s a matter of having this strong conviction: ‘My Guru has given me this instruction to ask myself “Who am I?” I will follow his instructions to the letter, and by doing so I will invoke his grace.’

That’s one attitude. But remember, he also said, ‘Intently hold onto this “I” thought. Be aware of it at all times.’ Don’t allow your mind to stray anywhere else. Keep it completely absorbed in the sense of ‘I’. If you do that, then this ‘I’ has to vanish. It can’t stand constant scrutiny.

Question: When should one do this practice? How often, and for how long?

David: To answer this I should like to qualify or expand on what I just said a little bit. Although Bhagavan said that you should, in every possible moment, be aware of what the mind is being distracted by and take it back to its source-thought ‘I’, at no time did he suggest that doing self-enquiry was a traditional sitting meditation practice that you did at fixed hours. On one occasion he actually said that sitting meditation was for novices. Nor did he follow the traditional Indian approach of advocating physical renunciation. There is no recorded instance of him ever giving permission to any of his devotees to give up any worldly obligations that they had. Sri Ramana taught that this practice of self-enquiry is something that you fit in at any time of the day, whenever your mind is not required for your work or your family. He didn’t think it necessary to go to a cave, go to a monastery, or find a secluded spot to practise this method. Sri Ramana said that if you do go to a remote place, you can’t leave your mind behind. You have to take it with you. He said that what needs to be given up is not your circumstances but your mind, the idea that ‘I am a particular person in particular circumstances’. Sri Ramana said that this attitude, this wrong belief, is your obstacle. Moving your body from one place to another isn’t going to overcome or eradicate it.

Many people who had very active family lives came to see Bhagavan to ask about the problems of following a spiritual practice in their busy lives. They had to support their family and found that this gave them little time for spiritual practice. To all these people Bhagavan would say, when they complained about how busy they were, ‘In whatever spare time you have, put your mind on this sense of ‘I’.’ He never said, ‘Make more time by giving up your work and family obligations’.

Sri Ramana said that everyone has some free time during the day. In that free time watch the ‘I’, be aware of it, see where it comes from, see how it manifests. You might be walking to work, eating your dinner, washing in the bathroom. In every person’s life there is at least a little time to be aware of the ‘I’. Use those free moments, said Bhagavan, to be aware of the ‘I’. Be aware of how it attaches itself to thoughts, how it goes out and plays with the world. Watch this process. Go back to this originating ‘I’ as often as you remember attention has wandered elsewhere, and then try to maintain awareness of it. Be aware of it by ceasing to be aware of all the things that it ordinarily wants to attach itself to.

You may have a life that you consider to be a busy one, filled with unavoidable commitments that keep you away from the Self. But within that life, if you can use your spare time to go back to the source and hold on to the ‘I’, Bhagavan says you’ll create a current, a current of awareness, a current of silence, a current of peace. The more you do this, the more this inner zone of silence will grow and intensify within you. Then, in those hours of the day when you have to do your job, when you have to look after your kids, the prevailing background current of silence will be there. When you encounter potentially agitating situations at work or in the family home, you will move into them and manage them while inhabiting a place of silence that you have created in your spare time. It is like having a bank account that you stock up with peace and silence. The silence, the capital, is there and available whenever you encounter potentially stressful situations that arise during the rest of the day.

Question: I have read that self-enquiry can be done by focusing on a particular place in the body, specifically, the heart-centre. Did Bhagavan recommend this?

David: One thing that some people have a fixed idea about is that self-enquiry involves focusing on a particular place in the body. This is, I would say, a misconception that has several origins. Ramana Maharshi used to say that the individual ‘I’ manifests first in the body in a small spot on the right side of the chest, and from there it jumps up to the brain and says ‘I am this body. This is me.’ Bhagavan said that if you do self-enquiry successfully, the ‘I’ will go back to this place on the right side of the chest and will ultimately disappear there. This has led many people to conclude that since Bhagavan asked them to find the source of the ‘I’, they could focus on this place which he said was the bodily source, and by focusing on this place they could make it disappear. Bhagavan never ever agreed with this supposition, and the reason for his opposition to it is in the explanation I gave earlier.

If your ‘I’ is looking at an object of attention, it has already extroverted itself. It has already risen to the brain. It is already up there going ‘Me, me, me. I’m now looking at something else.’ The only way to make the ‘I’ to go back to its source is to isolate it from all the objects, all the thoughts, all the perceptions that it normally hangs on to. When it has been completely shorn of all those associations, it gradually, slowly subsides back into this place, the heart-centre, and disappears. However, if you look at a place in the body, whether you are focusing on the sahasrara or the heart-centre, then your ‘I’ is externalised and working. It’s strong; it’s in the brain; its thinking; it’s doing the thing it likes best, which is creating a little world for itself. What it’s not doing is subsiding into its source. You cannot make the ‘I’ disappear by looking at an object, or imagining one. This is the essence of self-enquiry. Understanding this is fundamental to grasping why enquiry works and why other methods don’t work as well.

If you’re looking at an object, the subject is not going to subside. Once you get that piece of Ramana’s teachings fully established in your consciousness, you can’t go wrong. ‘I’ will only subside when it’s not looking at anything or thinking of anything. It will only disappear when it’s completely shorn of every possible thought and perception. Then and only will it go back to its source. Looking at a place in the body and imagining that the ‘I’ is there is not going to make the mind subside and vanish. The more you focus on a particular point, the more you strengthen the ‘I’ by making it hold onto an idea or a feeling that it is associating with.

In his Who am I? essay Sri Ramana said there are two categories of spiritual practice. There is what he called meditation (dhyana) and there is self-enquiry. He said meditation is when the ‘I’ looks at something, focuses on something, concentrates on something. These techniques might include saying your mantra, worshipping an image, or anything else that involves extroverting attention or putting it on an idea or a word. Self-enquiry, on the other hand, is focusing attention not on an object but on the subject who sees and perceives the object. Bhagavan taught that these are two entirely different paths. Meditation looks at or thinks of things. Enquiry is simply being subjectively aware of the ‘I’ who does all the thinking.

This idea that one needs to concentrate on the heart-centre is still endorsed by some people who are practicing enquiry or some form of it, but it has no support in any of Bhagavan’s replies on this topic. He did say that the heart-centre was a good place to concentrate on if one was drawn to focusing on a bodily location, but he never said that it should be a part of the practice of self-enquiry.

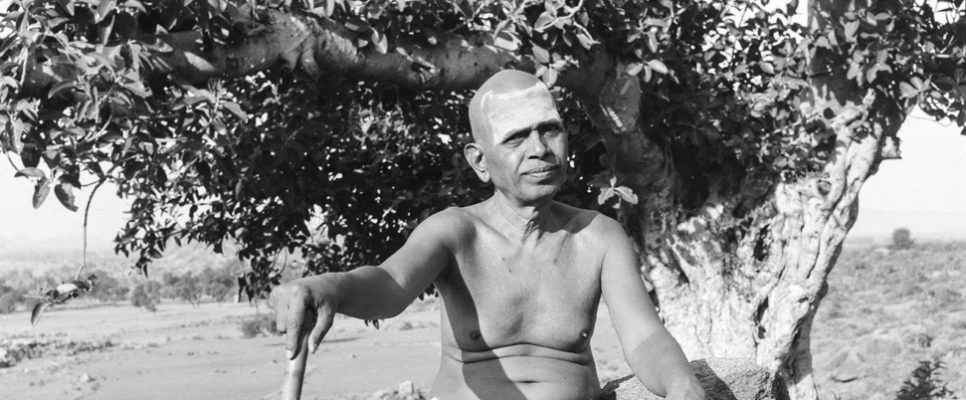

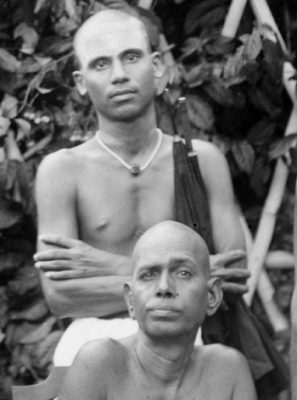

One comment on this subject that I really like comes from Annamalai Swami, one of Bhagavan’s devotees. Annamalai Swami said that when he first came to Ramanasramam, he started practicing self-enquiry by concentrating on the heart-centre. He told Bhagavan what he was doing, but Bhagavan discouraged him, saying, ‘No, no, no. That’s not the way to do it.’

After telling this story, Annamalai Swami gave a really lovely analogy. He said that just as electricity comes into your house at a particular point – where your meter is normally located – and then from that place spreads out to all your lights and sockets inside the house, there is a place in your body where the ‘I’ thought appears before it spreads out and says, ‘This is my body This is my mind.’ That place is the heart-centre.

Annamalai Swami said, ‘Just as you don’t experience electricity by staring at the meter box in your house, in the same way you don’t experience the Self by staring at the place in the body where the ‘I’ thought originates and rises to the brain.’

I can tell stories like this all day and people will still say, ‘Ah, but I’ve done that practice. I have visions when I do it. I get very peaceful. I get very blissful whenever I have concentrated on the heart-centre. It’s working for me. My mind is very quiet whenever I do this.’

My response to that is, ‘You’re having an experience’. The correct answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ is not bliss or a vision or an experience. It’s the extinction of the experiencer. If you’re still having an experience of bliss, if you’re seeing lights or visions or faces inside your spiritual heart, then you have projected your mind into a particular state. You are experiencing something very peaceful, very wonderful. What you’re not doing is making your individual ‘I’ disappear. You are utilising your ‘I’ to have a blissful experience and then using this experience to validate a completely wrong approach to self-enquiry. Self-enquiry, done properly, does not result in blissful experiences . It results in the disappearance of the experiencer.

My response to that is, ‘You’re having an experience’. The correct answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ is not bliss or a vision or an experience. It’s the extinction of the experiencer. If you’re still having an experience of bliss, if you’re seeing lights or visions or faces inside your spiritual heart, then you have projected your mind into a particular state. You are experiencing something very peaceful, very wonderful. What you’re not doing is making your individual ‘I’ disappear. You are utilising your ‘I’ to have a blissful experience and then using this experience to validate a completely wrong approach to self-enquiry. Self-enquiry, done properly, does not result in blissful experiences . It results in the disappearance of the experiencer.

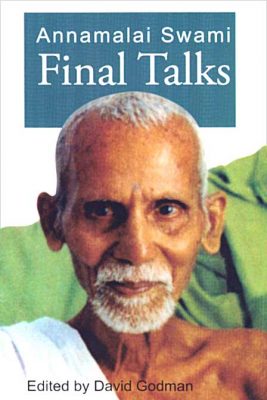

Annamalai Swami has given his own explanations of Bhagavan’s practical teachings on self-enquiry. These can be found in the final section of Living by the Words of Bhagavan and in Annamalai Swami: Final Talks. The first section of Final Talks can be read here. Both books are available from the ‘Books’ section of this site.